- Schmeller, Johann Andreas. Bayerisches Wörterbuch Buchstaben G, H, J (Cons.), K, Q, L, M, N; Sammlung von Wörtern und Ausdrücken, die in den lebenden Mundarten sowohl, als in der ältern und ältesten Provincial-Litteratur des Königreichs Bayern, besonders seiner ältern Lande, vorkommen, und in der heutigen allgemein-deutschen Schriftsprache entweder gar nicht, oder nicht in denselben Bedeutungen üblich sind, mit urkundlichen Belegen, nach den Stammsylben etymologisch-alphabetisch geordnet. Stuttgart: Tübingen: Cotta., 1828, p. 446: "Der Luft, L´úftling; Dim. das Lüf•tl•"

- Bronner, Franz Josef. Von deutscher Sitt' und Art. Munich: Verlag Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 309-32.

- Kiessling, Paula, and Waldemar Kiessling. Luftlmalerei. München: Verlag F. Bruckmann, 1959, p. 7: "Später hat man in der Literatur und in mannigfaltigen Veröffentlichungen auch andere Meister des al fresco mit diesem so heiter-musischen Beiwort geschmückt und die Hausmalerei dann einfach 'Lüftlmalerei' geheißen."

- Ricker, Julia. "Bilderbuchdörfer: Die Hohe Kunst Der Lüftlmalerei In Mittenwald Und Oberammergau." Monumente-Online.de, June 2016, https://www.monumente-online.de/de/ausgaben/2016/3/Lueftlmalerei_Mittenwald_Oberammergau.php. Accessed 31 Aug 2020: "Im Passionsspielort Oberammergau reihen sich Lüftlmalereien aus dem 18. bis 20. Jahrhundert wie Perlen an einer Kette, angefangen von der Ettaler Straße über die Dorfstraße und den Sternplatz bis zum Pilatushaus."

- Ricker, Julia. "Bilderbuchdörfer: Die Hohe Kunst Der Lüftlmalerei In Mittenwald Und Oberammergau." Monumente-Online.de, June 2016, https://www.monumente-online.de/de/ausgaben/2016/3/Lueftlmalerei_Mittenwald_Oberammergau.php. Accessed 31 Aug 2020: "Das Pilatushaus ist fraglos Höhepunkt von Zwincks Schaffen. Heute unvorstellbar: In den 1980er-Jahren war es vom Abriss bedroht, was engagierte Bürger verhinderten und damit den Künstler wieder ins öffentliche Bewusstsein rückten. Beauftragt hatte ihn 1784 Andreas Lang, der sich die Szene von Christus vor Pilatus für die Gartenseite seines Anwesens wünschte. Der Verleger selbst wirkte im Rahmen der Passionsspiele in der Rolle des Pilatus mit. Nach allen Regeln der Augentäuschung ruft Zwincks Malerei die Illusion einer Palastfassade hervor. Perspektivisch dargestellte Bauglieder, die Schatten werfen, lassen die biblische Geschichte auf einer fantastischen Bühne geschehen."

- Murray, John. A Handbook for Travellers in South Germany; Being a Guide to Bavaria, Austria, Tyrol, Salzburg, Styria, &c., The Austrian and Bavarian Alps, and The Danube from Ulm to the Black Sea; Including Descriptions of the Most Frequented Baths and Watering-Places; the Principal Cities, their Museums, Picture Galleries, Etc.; The Great High Roads; and the Most Interesting and Picturesque Districts. Also, Directions for Travellers and Hints for Tours. With an Index Map. London: John Murray, 3rd Ed., 1844, p. 119.

- Richard F. Burton, A Glance at the “Passion-Play” (London: W. H. Harrison, 1881), 48. "The aspect is not improved by the work of a certain Lüftelmaler or Freskomaler, Franz Zwinck, a curious character who, at the end fo the last century, treated sacred subjects in the most artless and incongruous fashion. He is the Paolo Veronese (say German handbooks) of the village."

- Bronner, Franz Josef. Von deutscher Sitt' und Art. Munich: Verlag Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 322-23: "Um die Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts, zu dessen Anfang einer der berühmtesten und hurtigsten Freskomaler aller Zeiten, Luka Giordano [genannt Fa-presto], sein reiches Leben beschloß, erblickte ein kleineres, doch in mancher Beziehung dem Vorgenannten ähnliches Genie das Licht der Welt: Ich meine Franz Zwinck, den sogen. Lüftlmaler, von Oberammergau."

- Bronner, Franz Josef. Von deutscher Sitt' und Art. Munich: Verlag Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 325: "Zwinck bei Knoller gelernt habe oder doch als Famulus bei ihm tätig gewesen sei, diese Meinung wird von manchen Kunsthistorikern bestritten. Im Jahre 1769 nämlich, asl Knoller das prächtige Deckengemälde im Chor der Ettaler Kirche schuf, malte Zwinck (am Hause Nr. 171) bereits ein Fresko (“Bergung der Leichs des hl. Johannes v. Nepomuk”), das in Bezug auf Farbenreiz, Stimmungund Zeichnung ein Meisterwerk ist. Zwinck stand damals im 21. Lebensjahre."

- Bronner, Franz Josef. Von deutscher Sitt' und Art. Munich: Verlag Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 331: "Weil Zwinck das Malen so schnell wie der Wind von der Hand gegangen und weil sein Gemüt stets heiter und lüftig gewesen sei, habe man ihn scherzweise den Lüftlmaler geheißen."

- Frietinger, Alois. Franz Zwinck, Der Lüftlmaler von Oberammergau. Erzählung. Regensburg: Verlagsanstalt vorm. Manz, 2nd Ed., 1930, p. 22: "Und du, mein lieber Ammergauer, ich möchte dich wegen deines windflüchtigen Sauselebens, noch mehr wegen der schier unglaublichen Schnelligkeit im Entwerfen und Ausführen, in dem du dem genialen Luka Giordano, den sie Fa presto, d.h. 'Machschnell!' nannten, gleichst, ich möchte dich gut deutsch einen 'Lüftlmaler' nennen -- du wirst, wenn dein Brausemost vergoren und du dich zum reinen Menschen durchgerungen hast, ein Großer werden!"

- Frietinger, Alois. Franz Zwinck, Der Lüftlmaler von Oberammergau. Erzählung. Regensburg: Verlagsanstalt vorm. Manz, 2nd Ed., 1930, p. 22: "Vor allem dem 'Lüftlmaler', wie Franz Zwinck von der Stunde an allgemein genannt wurde, war es, als sei in seinem Leben ein bedeutender Wendepunkt eingetreten."

- Carl B. Lievert, "Wie der Lüftlmaer zu seinem Namen kam." Goldenes Landl-Buch; Sammelband 1954 - 1956; Heimatbeilage Garmisch-Partenkirchner Tagblatt für die Täler an der Loisach, Isar und Ammer (Garmisch-Partenkircken: Adam Verlag, 1998), p. 72: "Die Abhandlung A. Frietingers am Bayernheft Nr. 38, Verlag Oldenburg, München, unter dem Titel: „Wie der Lüftlmaler zu seinem Namen kam” ist als eine liebenswürdige Novelle zu werten, entbehrt jedoch jedweder historisch belegbaren Grundlage und kann daher als Quelle nicht angeführt werden."

- Carl B. Lievert, "Wie der Lüftlmaer zu seinem Namen kam." Goldenes Landl-Buch; Sammelband 1954 - 1956; Heimatbeilage Garmisch-Partenkirchner Tagblatt für die Täler an der Loisach, Isar und Ammer (Garmisch-Partenkircken: Adam Verlag, 1998), p. 72: "Hauptlehrer J. R. Bührlen von Ettal vertritt in seiner fleißigen Arbeit über Zwink die ansicht, daß des Künstlers Beiname „Lüftlmaler” vorwiegend darauf zurückzuführen ist, daß er die meiste Zeit seines Lebens seinem mühsamen künstlerischen Erwerb in „luftiger Höhe” auf Gerüsten und Fahrstühlen nachging und das ganze Jahr über in der freien Natur an den Wänden der Häuser emsig schaffend tätig war."

- "Historic Ludwigstraße: A Street to Strut Along". Gapa.de, accessed 1 Sept 2020, https://www.gapa.de/en/Culture-health/Culture/Attractions/Historic-Partenkirchen.

- Kiessling, Paula, and Waldemar Kiessling. Lüftlmalerei. München: Verlag F. Bruckmann, 1959, p. 5: "Warum im übrigen sich Zwinck gerade diesen Beinamen beigelegt hat, ist nicht mehr sicher feststellbar."

- Kiessling, Paula, and Waldemar Kiessling. Lüftlmalerei. München: Verlag F. Bruckmann, 1959, p. 5: "Es mag sein, daß er dabei daran gedacht hat, wie luftig und etwas zugig es auf dem Gerüst stets war, von dem aus er mit eiligem Pinsel den feuchten Kalkbewurf bemalte, der nur auf so viel Fläche der Hauswand aufgetragen werden durfte, als er in einem Tag malerisch bewältigen konnte."

- Kiessling, Paula, and Waldemar Kiessling. Lüftlmalerei. München: Verlag F. Bruckmann, 1959, p. 5-6: "Jedenfalls ist Zwinck auch mit seinem Beinamen etwas besonders Graziöses eingefallen, und wir können uns gut vorstellen, wie ihm eines Tages auf seinem Gerüst, als er vielleicht gerade ein Liedl vor sich hinpfiff, plötzlich das Wort “Lüftlmaler” in den Sinn gekommen ist."

- Bronner, Franz Joseph. Von Deutscher Sitt' und Art. Munich: Verlag Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 331: "Übrigens Zwinck kam auch mit seiner Kunst nie zu großem Reichtum.

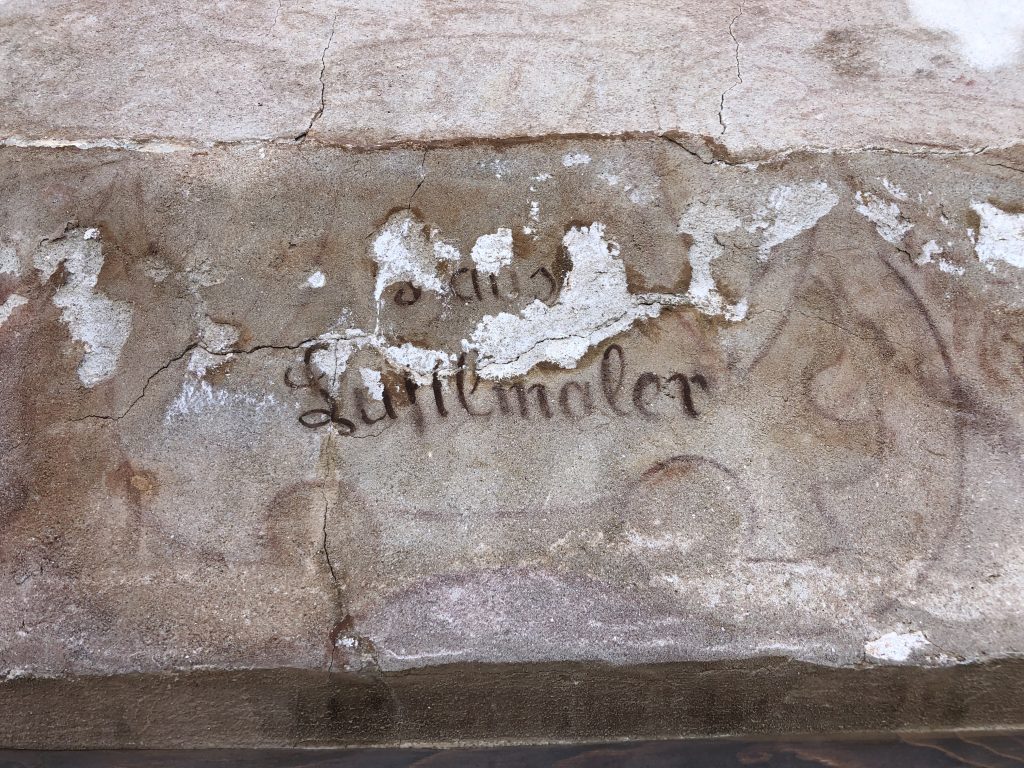

Doch ein kleines, trautes Heim erübrigte er sich: Haus Nr. 156 in der unteren Gasse an der Ammer. Noch vor ca. 30 Jahren nannte es der Volksmund ‚beim Lüftlmaler'." - Dikova, Valia. Alte Häuser in den Ammergauer Alpen – Judashaus in Oberammergau. Blog: "Oberamergau erleben!" Accessed 2021-04-20. https://www.oberammergau-erleben.de/alte-haeuser-in-den-ammergauer-alpen-judashaus-in-oberammergau/: "Dieses Haus ist einer der ersten bürgerlichen Häuser, die mit Fresken außen bemalt wurden. Der Hausname ist „Lüftl“, der auch noch schwach über der Eingangstür zu sehen ist. Ob der Name dem Handwerk oder andersrum gegeben hat, lässt sich leider nicht mehr wissenschaftlich rekonstruieren. Es ist ein Handwerkerhaus mit einem zweigeschossiger nordwestlich abgeschrägtem Flachsatteldachbau mit Zierbund und Fassadenmalerei, gebaut in der ersten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts, übergangene Fresken von Franz Seraph Zwinck um 1780."

- Kiessling, Paula, and Waldemar Kiessling. Luftlmalerei. München: Verlag F. Bruckmann, 1959, p. 7: "Er nämlich wohnte im Haus Nr. 98, das die Kloster Ettaler Säkularisationsakten als “Lüftl mit 1/32 Hoffuss” ausweisen. Es handelt sich bei “Lüftl” um einen Hausnamen für die Familien Zwinck, was auch eine pfarramtliche Eintragung vom Jahre 1839 in Oberammergau noch beweist. “Lüftl” als Familiennamen waren im Landkreis Garmisch-Partenkirchen noch zwei weitere belegt. Die Forschungen eines Nachkommen des Malers Franz Zwinck, der aus dem Lüftl-haus stammte, Alfred O. Zwinck in Oberammergau belegten urkundlich diese Zusammenhänge."

- Dewiel, Lydia L. Oberbayern: Kunst und Landschaft zwischen dem Altmühltal und Alpen Mit Rundgängen durch die Landeshauptstadt München. München: DuMont Reiseverlag, 1996, pp. 248-49: "Als Franz Seraph bereits ein viel beschäftigter Freskant war, bewohnte er in Oberammergau das Haus »zum Lüftl« in der Judasgasse. Nicht die Arbeit an der frischen Luft trug also dem Fassadenmaler seinen Namen ein — es war sein Haus, das ihn zum Lüftlmaler machte."

- Meider, Herbert and Franz Stoltefaut. Lüftlmalerei an Isar, Partnach, Loisach und Ammer. Media-Verlag Schubert, 2003, p. 4: "oder von einem Korbinian, Ignaz oder Josef Lüftl, der die ersten Malereien dieser Art geschaffen haben sollte."

- For example:

• Waldstein, Mella. "Waldviertel: Die Lüftlmalerei". Kultur.Region Schaufenster. Volkskultur Niederösterreich GmbH, Atzenbrugg, Österreich, September 2012, p. 30: "Da wird ein Josef Lüftl als Künstler genannt."

• Schetar, Daniela and Friedrich Köthe. Servus im Oberland: Bier, Barock und Badeseen. Gmeiner-Verlag, 2014: "Warum die bunten Bilder 'Lüftlmalereien' heißen, ist unbekannt: Kommt 'Lüftl' von der luftigen Höhe, in der die Künstler arbeiten müssen? War ein Maler namens Josef Lüftl der Erfinder dieser Freskotechnik? Oder ist das Oberammergauer Haus 'Zum Liftl' der Geburtsort?"

• Bauer, Hans-Peter Dinesh. "Lüftlmalerei – Hof & Herrgott". My Marterl, 12 February 2014, https://mymarterl.wordpress.com/2014/02/12/luftlmalerei-hof-herrgott/. Accessed 2 Sept 2020: "In einer anderen Version fungiert ein tonangebender Vertreter dieser Stilrichtung namens Josef oder Ignaz Lüftl als Namenspatron."

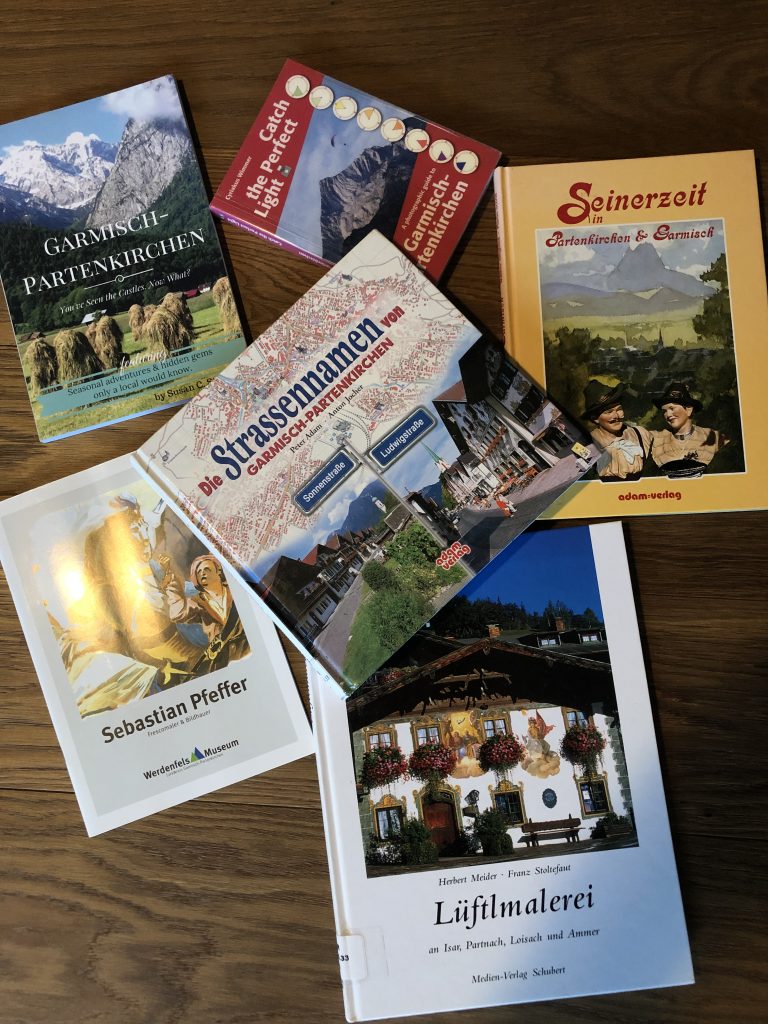

Lüftlmalerei

A street by street guide to the fresco and facade paintings in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district