- Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. Phaidon, Pocket Ed., 2006, p. 49.

- Talbot, Margaret. "Color Blind". The New Yorker, October 29, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/29/the-myth-of-whiteness-in-classical-sculpture. Accessed 28 Aug 2020. Quoting Mark Abbe, a professor of ancient art at the University of Georgia: "the idea that the ancients disdained bright color 'is the most common misconception about Western aesthetics in the history of Western art.' It is, he said, 'a lie we all hold dear.'"

- Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. Phaidon, Pocket Ed., 2006, pp. 70-71.

- Escherich, Mela. Die schule von Köln. Strassburg: Heitz & Mündel, 1907, p. 2: "Damals drängte sich das moderne Leben auf einzelne große Verkehrsadern zusammen. Die Kultur zog ihre bestimmten Linien."

- Brown, Peter. The Cult of the Saints. The University Of Chicago Press, 2015, p. xxvii.

- Brown, Peter. The Cult of the Saints. The University Of Chicago Press, 2015, p. 9.

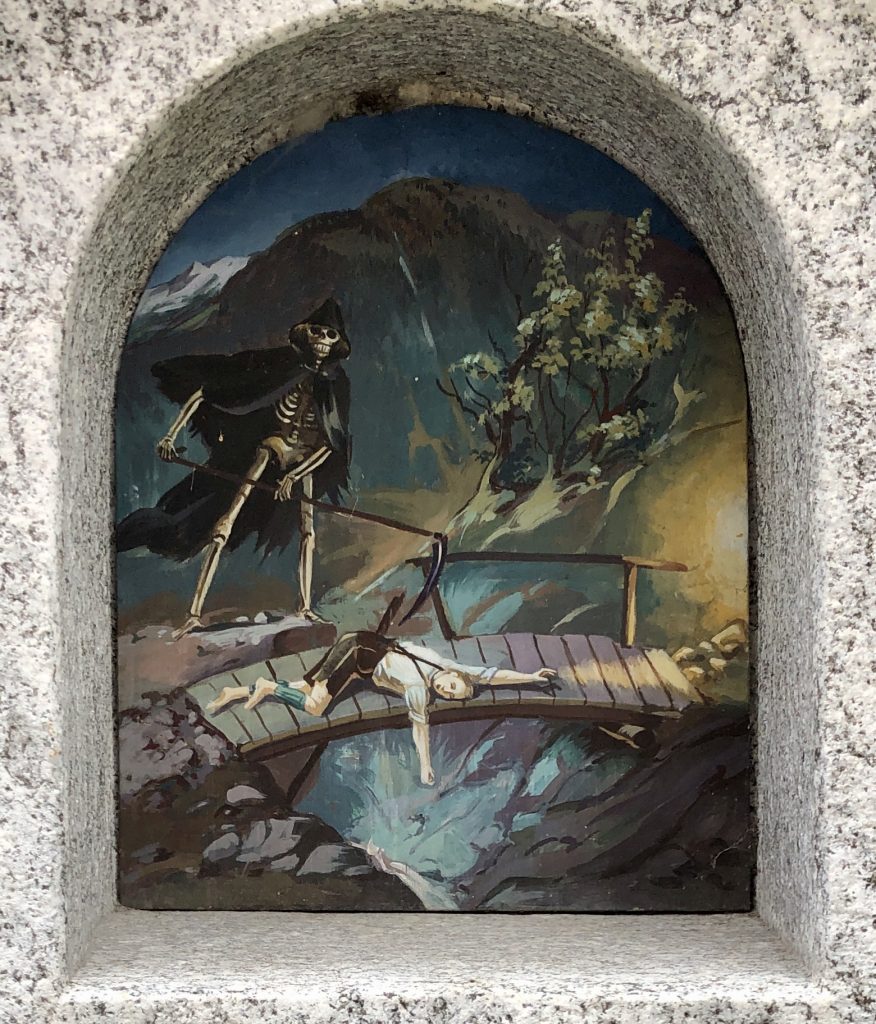

- Rattelmüller, Paul Ernst. Lüftlmalerei in Oberbayern. Werbeabteilung Süddeutscher Verlag, 1960, p. 7-8: "Fassadenmalerei in unserem Sinn beginnt wohl mit den ersten Außenmalereien an Kirchen. Das ganze Mittelalter hindurch kann man sie verfolgen, vor allem aber in der Gotik im Zusammenhang mit dem Entstehen großer verputzter Flächen. Da ist wohl eines der häufigsten Motive der heilige Christophorus, vor allem an großen Pilgerstraßen, denn Fuhrleute, Reisende und Pilger waren in [8] jener Zeit der festen überzeugung, daß sie an dem Tag, an dem sie das Bild des Heiligen gesehen hätten, nicht vom Tod überrascht würden."

- Hildebrandt, Hans. Wandmalerei, Ihr Wesen Und Ihre Gesetze. Mit 462 Abbildungen, Darunter 266 Hilfszeichnungen Des Verfassers. Deutsche Verlags-Anstali, 1920, p. 276. "Nicht allein Wohnhäuser pflegte man seit den Tagen der Renaissance an den Schauwänden zu bemalen. Monumentalbauten wie Rathäuser, Tortürme usw. mußten, ihrer das Stadtbild beherrschenden Stellung zuliebe, erst recht mit prunkreichem Schmuck bedacht werden. Bei der Stoffwahl entschied wohl meist der Wunsch, die Macht des Gemeinwesens zu verherrlichen, so daß vor allem bedeutsame Ereignisse, siegreiche Schlachten, Bewillkommnungen von Fürsten usw., herangezogen wurden. Die Wiederherstellungen haben indessen an den Rathäusern, die heute noch Fassadengemälde aufweisen — zu Ulm, zu Lindau usw. — so viel verdorben, daß von den ursprünglichen Reizen kaum mehr etwas zu entdecken ist. Tortürme stattete man gern mit imponierender Wiedergabe des von Kriegern gehaltenen Stadtwappens aus."

- Peltzer, Alfred. Deutsche Mystik und Deutsche Kunst. Strassburg: Heitz & Mündel, 1899, p. 91: "Sie bauen grosse und stattliche Häuser, lassen allerlei Affenwerk und Leichtfertigkeit daran malen, zieren sie sonst innwendig und ausswendig vom Dach an bis auf den Boden auf mancherlei und unnötige Weise: dass mann sich nicht genugsam verwundern kann, wie sie doch allenthalben nur ihrer Sinne Lust und Ergetzlichkeit suchen."

- Escherich, Mela. Die schule von Köln. Strassburg: Heitz & Mündel, 1907, p. 11: "Wir sind heute nicht mehr in der Lage, sein Urteil nachzuprüfen; denn von der flüchtigen Modekunst jener Tage hat sich so gut wie nichts erhalten. Ueberliefert ist uns nur, daß eine profane Richtung bestand, eine Ausläuferin der romanischen Sakralkunst. Die eindringende Gotik verwehrte der Malerei die bisher behaupteten großen Wandflächen. Da flüchtete sich die aus der Kirche Verdrängte in das Bürgerhaus, wo sie freundliche Aufnahme fand. Aber hier mußte sie ihr Wesen verwandeln. Hier mußte sie Geschichten erzählen. Keine Legenden und Passionen, wenngleich Erbauliches. Also sittliche Geschichten, moralische Anekdoten. Sie wurden dann gewürzt mit närrischen Randglossen, Drolerien, mit derben Witzen, — Affenwerk, wie Tauler es nannte."

- Escherich, Mela. Die schule von Köln. Strassburg: Heitz & Mündel, 1907, p. 11: "Die romanische Wandmalerei war eine vorwiegend epische gewesen. Dieser Charakter erhielt sich. Aber von der großen Mauerfläche ging es jetzt in den kleinen Raum der Wohnstube hinein, vom großen klassischen Stil in den der engen Bürgerwirtschaft. Die breite epische Form verlor sich in spielerischem Geplauder. Die Wandfriese der Bürgerhäuser mochten wohl allerlei drolliges Genre aufweisen; aber wohl kaum Leistungen, die Zukunftswerte in sich bargen. Darum fielen sie auch dem Zahn der Zeit zum Opfer."

- Hildebrandt, Hans. Wandmalerei; Ihr Wesen Und Ihre Gesetze, Mit 462 Abbildungen, Darunter 266 Hilfszeichnungen Des Verfassers. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstali, 1920, p. 274: "Und diese bunte, systemlose, aber prachtreiche Scheinarchitektur, die auch bei schlichten Wohnhäusern mit Motiven des Palastbaus prahlt und die allerorten Durchblicke ins Freie erschließt, wird bevölkert mit naturgetreu gemalten, aber meist überlebensgroßen Gestalten, mit modisch gekleideten Herren und Damen, die miteinander reden und tändeln oder, über Teppiche sich lehnend, auf die Straße hinabblicken, und dicht daneben mit nicht minder körperhaft wiedergegebenen allegorischen Figuren und mit den angestaunten Helden der Antike. Auch der Humor darf sein Wesen treiben. [...] Besonders gern brachte man in der deutschen Renaissance Darstellungen an, die etwas Überraschendes, ja fast Erschreckendes an sich hatten, und bei denen die Erzeugung vollkommener Täuschung Selbstzweck war, Darstellungen wie die eines Reiters, der über das Geländer einer Terrasse mit jähem Sprung auf die Straße zu setzen scheint."

- Hildebrandt, Hans. Wandmalerei; Ihr Wesen Und Ihre Gesetze, Mit 462 Abbildungen, Darunter 266 Hilfszeichnungen Des Verfassers. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstali, 1920, p. 275: "Auch die oft sehr reizvollen, wenn auch manchmal handwerksmäßig-primitiven Malereien an den Außenwänden oberbayerischer und tiroler Bauernhäuser zeigen meist, da sie fast durchweg dem 18. Jahrhundert entstammen, die nämlichen Eigentümlichkeiten."

- Hildebrandt, Hans. Wandmalerei; Ihr Wesen Und Ihre Gesetze, Mit 462 Abbildungen, Darunter 266 Hilfszeichnungen Des Verfassers. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstali, 1920, p. 275: "Biblische Darstellungen überwiegen an den Fassaden dieser Bauernhäuser. Doch finden sich auch Hinweise auf das Gewerbe des Hauseigentümers."

- Hildebrandt, Hans. Wandmalerei; Ihr Wesen Und Ihre Gesetze, Mit 462 Abbildungen, Darunter 266 Hilfszeichnungen Des Verfassers. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstali, 1920, p. 275: "Die Mauern der bayerischen und tiroler Bauernhäuser sind fast immer weiß verputzt, so daß die Fassadenmaler der volkstümlichen Lust an bunten, heiteren Farben ungehemmt frönen durften."

- Rattelmüller, Paul Ernst. Lüftlmalerei in Oberbayern. Werbeabteilung Süddeutscher Verlag, 1960, p. 8: "Fassadenmalerei findet man vor allem in Süddeutschland. Die Grenze dürfte etwa beim Main liegen. In Franken waren die Malereien allerdings nie sehr zahlreich, weil der Fachwerkbau in diesen Gebieten gar nicht die großen Flächen geboten hat wie eine verputzte Fassade."

- Böröcz, József. "Travel-Capitalism: The Structure of Europe and the Advent of the Tourist", Comparative Studies in Society and History, 39, 4, October 1992, p. 727.

- Staël, Madame de Anne-Louise-Germaine. De L'allemagne. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1852, p.15: "Les maisons, dans plusieurs villes, sont peintes en dehors de diverses couleurs: on y voit des figures de saints, des ornements de tout genre, dont le goût n'est assurément pas parfait, mais qui varient l'aspect des habitations et semblent indiquer un désir bienveillant de plaire à ses concitoyens et aux étrangers. L'éclat et la splendeur d'un palais servent à l'amour-propre de celui qui le possède; mais la décoration soignée, la parure et la bonne intention des petites demeures ont quelque chose d'hospitalier."

- Murray, John. A Handbook for Travellers in South Germany; Being a Guide to Bavaria, Austria, Tyrol, Salzburg, Styria, &c., The Austrian and Bavarian Alps, and The Danube from Ulm to the Black Sea; Including Descriptions of the Most Frequented Baths and Watering-Places; the Principal Cities, their Museums, Picture Galleries, Etc.; The Great Hight Roads; and the Most Interesting and Picturesque Districts. Also, Directions for Travellers and Hints for Tours. With an Index Map. London: John Murray, 3rd Ed., 1844, p. 34.

- Murray, John. A Handbook for Travellers in South Germany; Being a Guide to Bavaria, Austria, Tyrol, Salzburg, Styria, &c., The Austrian and Bavarian Alps, and The Danube from Ulm to the Black Sea; Including Descriptions of the Most Frequented Baths and Watering-Places; the Principal Cities, their Museums, Picture Galleries, Etc.; The Great Hight Roads; and the Most Interesting and Picturesque Districts. Also, Directions for Travellers and Hints for Tours. With an Index Map. London: John Murray, 3rd Ed., 1844, p. 119.

- Rattelmüller, Paul Ernst. Lüftlmalerei in Oberbayern. Werbeabteilung Süddeutscher Verlag, 1960, p. 20: "Wohl der erste, der sich mit dieser Art Fassadenmalerei beschäftigt hat, dürfte Joseph Bronner gewesen sein, der bereits vor und um die Jahrhundertwende mit einem Photoapparat bewaffnet, Jagd auf solche Bauernhäuser gemacht hat."

- Bronner, Franz Joseph. Von Deutscher Sitt' und Art, 1908, Volkssitten und Volksbräuche in Bayern und den angrenzenden Gebieten (im Kreislauf des Jahres dargestellt), mit einem Anhang über Friedhöfe und Freskomalerei. Munich: Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 305: "Auf meinen zahlreichen Wanderungen durch das bayerische Hochland habe ich anfänglich auch nur aus Liebhaberei das eine oder andere bildergeschmückte Bauernhaus, das mir besonders ins Auge stach, abgeknipst. Später ging ich zielbewusst den Spuren alter freskomalerei nach und scheute ost den 4-5 Stunden weiten Weg zu abgelegenen Einödhöfen nicht. Heute liegt vor mir eine Sammlung von 120 freskengeschmückten Gebirgshäusern; zwei Notizbücher sind mit Inschriften und Sinnsprüchen von alten Bauernhäusern vollgeschrieben; die Bilder und Schriften sind verglichen und ich glaube, das Ganze überblicken, sagen zu dürfen: Was uns da vor Augen tritt, ist ein Stück deutschen Volkstums, das in seiner Eigenart und Kernhaftigkeit die Beachtung und Wertschätzung weiter Kreise verdient."

- Fürlinger, Ulla. "Wand-Lungen". Kulturberichte Aus Tirol Und Südtirol: Architekturen, 2010, pp. 115, https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/kunst-kultur/abteilung/Publikationen/Themenheft_2010_Architekturen.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2020: "Ist es ein leiser aber sichtbarer Protest gegen die schneller und 'größer' werdende Welt? Ein Mahnmal? Vielleicht deutlicher Ausdruck einer patriotischen Gesinnung? Demonstrativ gezeigter Stolz auf die alpine Gegend? Oder Angst vor dem gefühlten Verlust eben dieses Idylls? Ist es Verstärker des echten Idylls? Oder legt man sich eine Malerei zu, weil der Nachbar auch eine an der Fassade hat und man am eigenen Haus eine fensterlose Wand, die nach „Dekor“ verlangt".

- Bronner, Franz Joseph. Von Deutscher Sitt' und Art, 1908, Volkssitten und Volksbräuche in Bayern und den angrenzenden Gebieten (im Kreislauf des Jahres dargestellt), mit einem Anhang über Friedhöfe und Freskomalerei. Munich: Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 305: "Was uns da vor Augen tritt, ist ein Stück deutschen Volkstums, das in seiner Eigenart und Kernhaftigkeit die Beachtung und Wertschätzung weiter Kreise verdient."

- Ricker, Julia. "Bilderbuchdörfer: Die Hohe Kunst Der Lüftlmalerei In Mittenwald Und Oberammergau." Monumente-Online.de, June 2016, https://www.monumente-online.de/de/ausgaben/2016/3/Lueftlmalerei_Mittenwald_Oberammergau.php. Accessed 31 Aug 2020: "In Mittenwald hat sich Regine Ronge den Lüftlmalereien verschrieben. Bis in die letzten Winkel des Alpendorfs kennt sie die farbenfrohe Häuserzier. „Das Wissen um das Alter, die Urheber und die Bedeutung der Malereien ist bei vielen Menschen nicht mehr vorhanden“, berichtet sie. „Früher wurde es von Generation zu Generation weitergetragen.“ Heute spürt sie der Geschichte jedes einzelnen Werks nach, sucht nach historischen Fotos und befragt die Mittenwalder, damit überlieferte Informationen nicht verloren gehen."

- Bronner, Franz Joseph. Von Deutscher Sitt' und Art, 1908, Volkssitten und Volksbräuche in Bayern und den angrenzenden Gebieten (im Kreislauf des Jahres dargestellt), mit einem Anhang über Friedhöfe und Freskomalerei. Munich: Max Kellerer, 1908, p. 306: "Die alten freskomalereien unserer Alpenlandschaft stammen fast durchweg aus der Zeit von Mitte bis Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts (ca. 1750-1800). Dies läßt sich folgendermaßen erklären: Die Erbfolgekriege waren vorüber und eine gewisse Behäbigkeit war beim Bauernstand wieder eingekehrt. Der beträchtliche Rottverkehr zu Wasser und zu Land e brachte das Alpenland in lebhafte Verbindung mit schönen Städten des flachlandes und größeren Nachbarorten, die oft prächtigen fassadenschmuck auszeigten. Das regte zur Nachahmung an. Ein oder der andere Wohlhabende ließ sich sein Haus bemalen; solches gefiel dem Nachbarn und nun mußte sein Heim in ähnlicher Weise geschmückt werden. Entsprach dies doch dem frommen Sinn und künstlerischen Empfinden des Volkes zugleich! Man ließ sich besondere Lieblingsheilige ausmalen und gab so dem Hause nicht bloß eine Zier, sondern gewissermaßen einen christlichen Schuß. Die Sinnsprüche an den Häusern bildeten eine stete Quelle der Erbauung und gingen als Weisheits- und Lebensregeln (in jener Zeit mangelhafter Volksschulbildung) von Mund zu Mund. In glücklichem Zusammentreffen mit solchem Bedürfnis nach Heimatschmuck erstanden damals im Alpervolke einheimische geniale Meister der farbe, die um billigstes Entgelt den Wünschen der Bevölkerung Rechnung trugen."

Lüftlmalerei

A street by street guide to the fresco and facade paintings in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district