Marienplatz

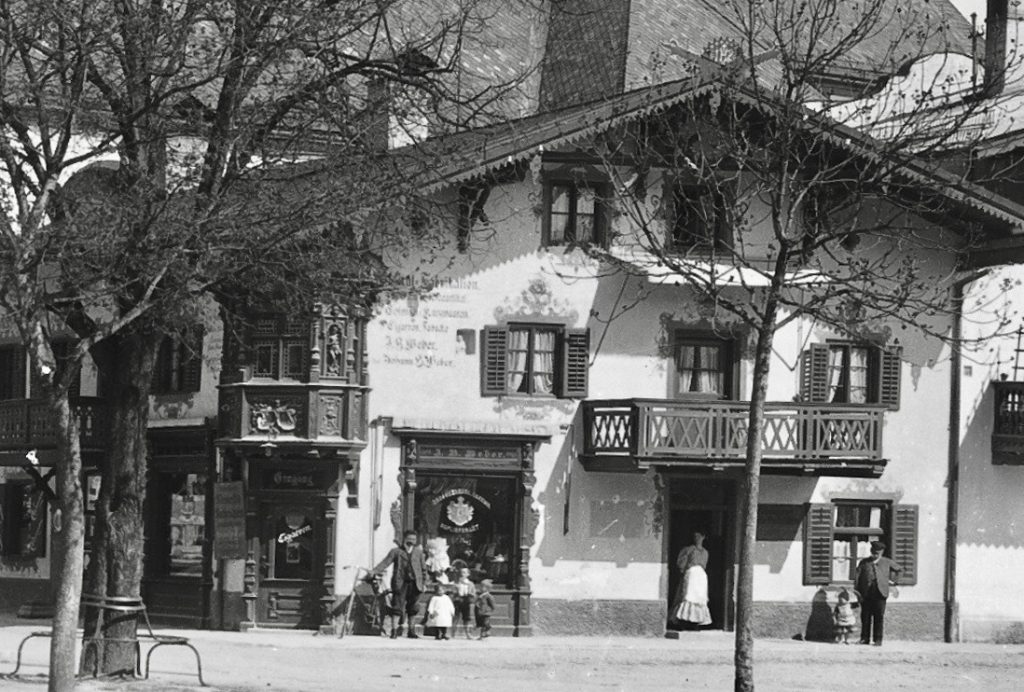

Marienplatz 2.

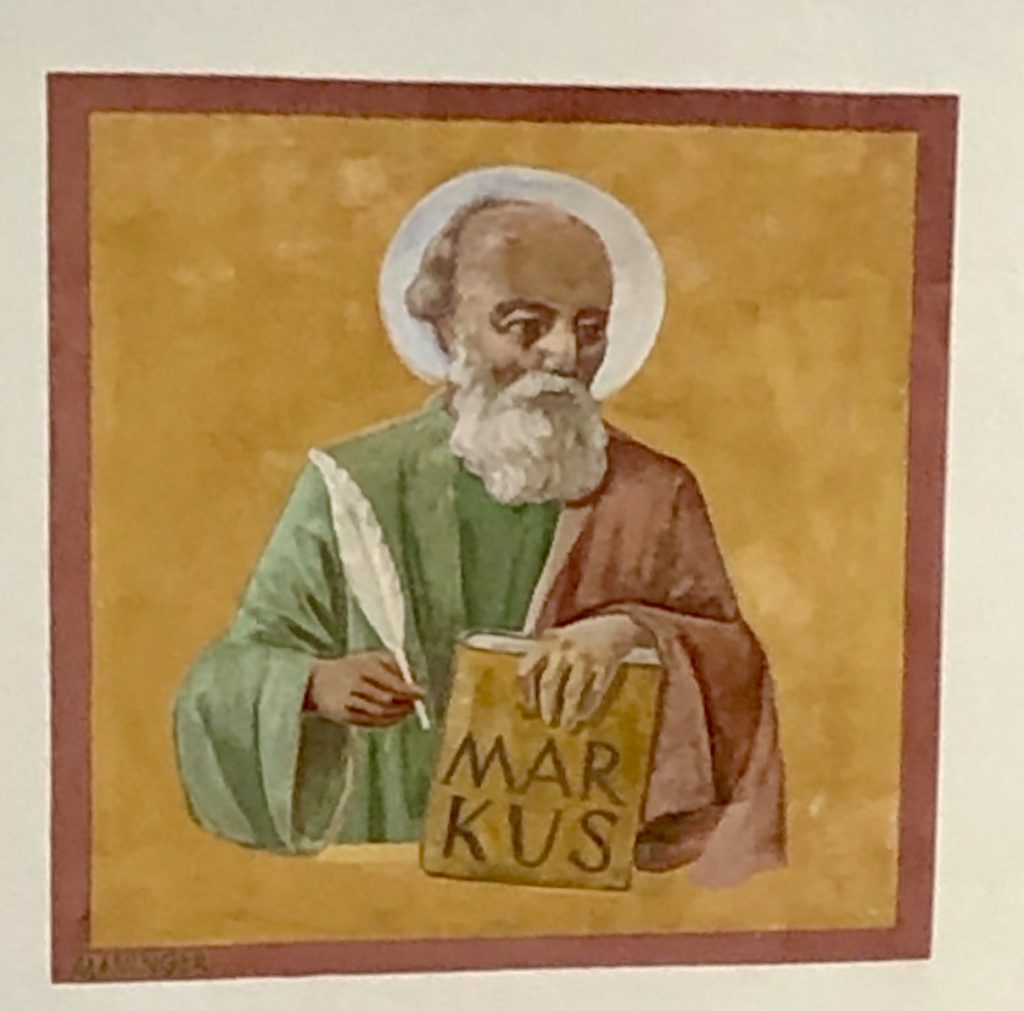

Lüftlmalerei by August Maninger.

Marienplatz 2a.

Marienplatz 4.

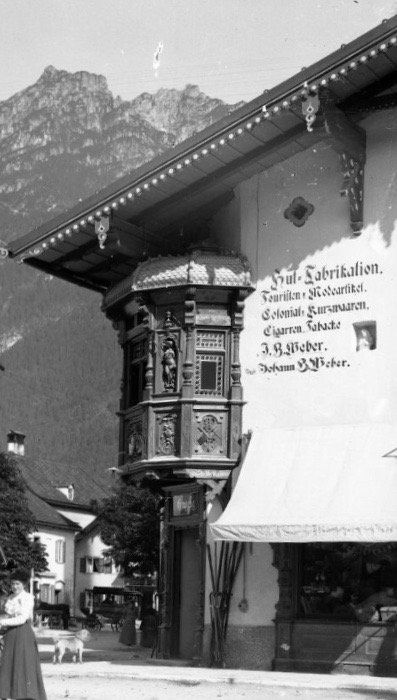

Hutfabrikation,

Touristen und Modeartikel.

Colonial und Kurzwaaren,

Cigarren, Tabacke

von J. B. Weber.

Und Johann B. Weber.

Or: “Hat manufacturing, tourist and fashion items. Colonial Haberdashery, cigars, tobacco by J. B. Weber. And Johann B. Weber.”

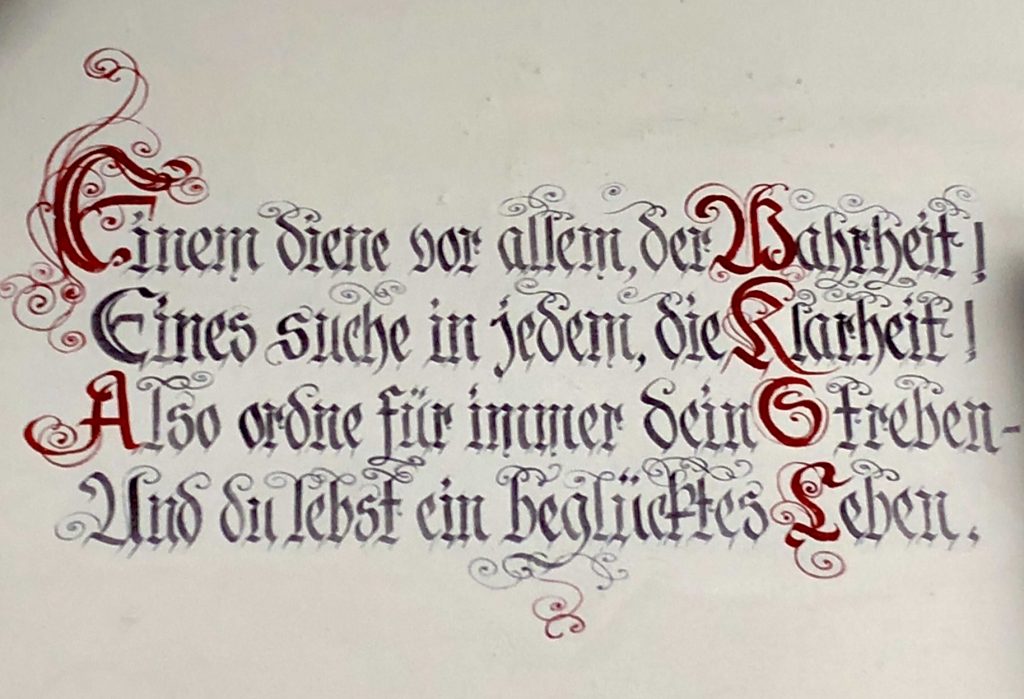

Today, in that same space above the door, a more aspirational message:

Einem diene vor allem, der Wahrheit!

Eines Suche in jedem, die Klarheit!

Also ordne für immer dein Streben-

Und du lebst ein beglücktes Leben.

Or: “Above all, serve the truth! Search for one thing, clarity! Always strive for these, and you will live a happy life.”

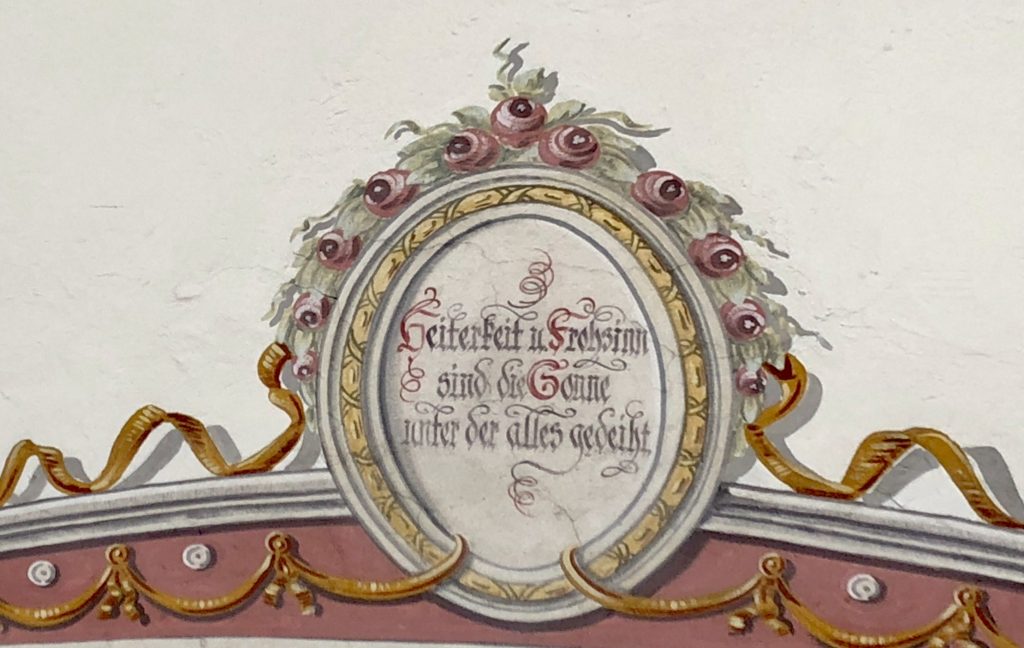

Beside that, above the window, a quote from German writer Jean Paul (1763 – 1825): “Heiterkeit und Frohsinn sind die Sonne, unter der alles gedeiht”.

Or: “Happiness and cheerfulness are the sun under which everything thrives”.

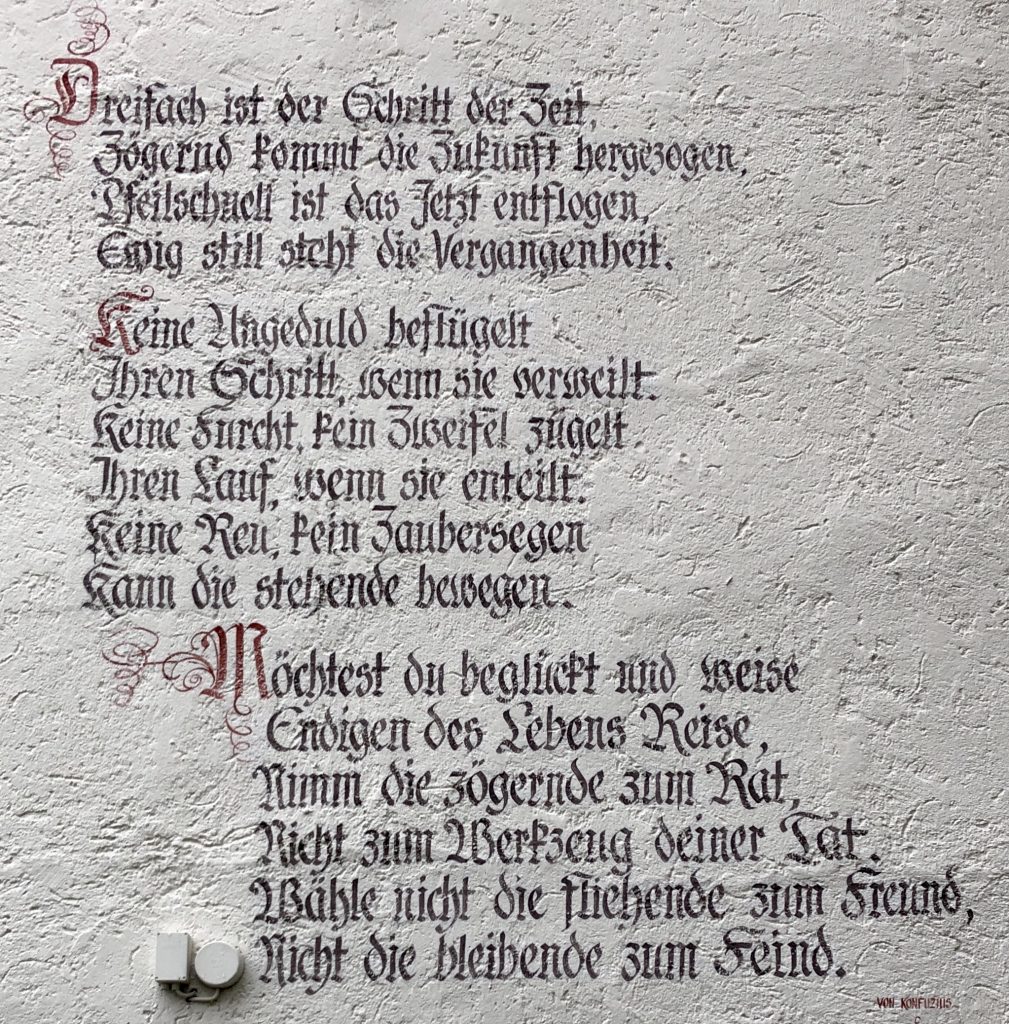

On the back of the building, a portion of “The Proverbs of Confucius,” a poem by Friedrich Schiller (1759– 1805):

Dreifach ist der Schritt der Zeit:

Zögernd kommt die Zukunft hergezogen,

Pfeilschnell ist das Jetzt entflogen,

Ewig still steht die Vergangenheit.

Keine Ungeduld beflügelt

Ihren Schritt, wenn sie verweilt.

Keine Furcht, kein Zweifeln zügelt

Ihren Lauf, wenn sie enteilt. Keine Reu, kein Zaubersegen

Kann die stehende bewegen.

Möchtest du beglückt und weise

Endigen des Lebens Reise,

Nimm die zögernde zum Rat,

Nicht zum Werkzeug deiner Tat.

Wähle nicht die fliehende zum Freund,

Nicht die bleibende zum Feind.Friedrich Schiller von "Sprüche des Konfuzius"

Or:

Threefold is the march of time

While the future slow advances,

Like a dart the present glances,

Silent stands the past sublime.

No impatience e'er can speed him

On his course if he delay;

No alarm, no doubts impede him

If he keep his onward way;

No regrets, no magic numbers

Wake the tranced one from his slumbers.

Wouldst thou wisely and with pleasure,

Pass the days of life's short measure,

From the slow one counsel take,

But a tool of him ne'er make;

Ne'er as friend the swift one know,

Nor the constant one as foe!Friedrich Schiller from "The Proverbs of Confucious"

There are two, huge lüftlmalerei on Marienplatz 5, “The Ostlerhaus,” both painted by Heinrich Bickel in 1933, and both depicting historically significant events.

The mural on the edge of the building depicts the doomed rebellion against the occupying Austrian force in Sendling on Christmas Day in 1705.

After a defeat at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, fled, leaving Bavaria to the victorious Austrian Hapsburg Empire. While Bavaria was occupied by Austrian troops, the Hapsburg Empire imposed a new set of taxes, to which the Bavarian people rebelled.

At first, there was little response from the Austrians, and the rebellion spread from the outer reaches to the Bavarian capital of Munich. However, on the night of December, 25, 1705, Hapsburg soldiers confronted the rebels near Sendling outside of Munich. The battle is now known as the Sendling Christmas Day Massacre (“Sendlinger Mordweihnacht“, in German), as an estimated 1,100 Bavarians were killed — some supposedly even after surrendering — while the Austrians lost only about 40 men.

That particular battle became a symbolic legend in Bavaria. And no hero of the rebellion was more legendary than the Blacksmith from Kochel. More than 70 years old and standing more than 7 feet (2 meters) tall, he supposedly fought in the revolt that Christmas morning with a 100 lbs. (50 kg) spike-studded club in one hand and the Bavarian flag in the other.

In 1830, the Mainz painter Wilhelm Lindenschmit the Elder painted The Blacksmith as the dominant figure in the center of his fresco depicting the battle on the wall of the Sendlinger church.

The lüftlmalerei at Marienplatz 5 now in Garmsich is actually a reproduction of another work, “The Storming of the Red Tower in Munich by the Blacksmith from Kochel on Christmas Morning in the Year 1705,” (“Erstürmung des Roten Turmes zu München durch den Schmied von Kochel am Weihnachtsmorgen des Jahres 1705“), originally painted by Franz von Defregger in 1881.

The lüftlmalerei artist here highlights the opposing forces by use of their respective flags: replacing the streaked white and blue Bavarian flag in von Degregger’s painting for a checkered one, and painting the door of tower with the checkered yellow and black banner of the city of Munich.

On the front of the building, “Raftsmen from 1730” shows the advancement of travel through Garmisch-Partenkirchken in 100 year intervals.

Starting at the bottom, in “1730,” Bickel painted men traveling down the Partnach river on a raft made of rough hewn logs.

Adopting the idyllic style of Albin Egger-Lienz, Bickel depicts these raftsmen as Herculean, primevally powerful mountain men. Their faces, framed by mustaches, are angularly drawn, their eyes fixed on the work that they are doing, showing no emotion or fear for their safety. The artist idealizes the mountain worker as a hero in the struggle with nature. One can see the obvious influence in Bickel’s raftsmen, here, from Egger-Lienz’s “Two Mountain Mowers” (1913).

Next, in the center, in “1830,” a Postillon travels down the road on a horse drawn carriage while blowing a trumpet.

Postillon wore uniformed clothing and carried a post horn or, at times in the 19th century, a post trumpet — now the symbol for the German postal system. This made it clear and possibly also audible that he was authorized to accept mail and that he had priority when using traffic routes, ferries and bridges. In the 1800s, Postillons were posted and paid for by the post keepers at Post Hotels.

Finally, at the top, in “1930,” the Zugspitzbahn railway.

The Zugspitzbahn railway was built between 1928 and 1930 and first went into operation on February 19, 1929. The line — which is still in operation — runs from the center of Garmisch-Partenkirchen to the Zugspitzplatt, just below the Zugspitze mountain, the highest mountain in Germany. It terminates 2.6 kilometers above sea level, making it the highest railway in Germany and the third highest in all of Europe.

The Parish Church of Saint Martin at Marienplatz 6 was built between 1730 and 1734 on the site of a previous chapel to Saint Nicholas, which was demolished.

Inside, the plaster work was done by master plasterer Josef Schmuzer from Wessobrunn, the ceiling was painted by master painter Matthäus Günther, and the fresco paintings on the walls were done by none other than the original “Lüftlmaler from Oberammergau” himself, Franz Zwinck.

Outside, a Coat of Arms above the door and a sundial on the wall above.

Although there are no lüftlmalerei on the walls of Marienplatz 9 now, as you can see in these photos, it formerly had a few.

At the Bavarian State Archives online, you can see a picture of the lüftlmalerei on this building as they looked in 1932, and a picture of how this building looked without any lüftlmalerei by 1964.

The building at Marienplatz 10 was originally built in 1792 on the site of the old court blacksmith.

The design and the decorative stucco work are said to have been carried out by Italian craftsman, since the owner who built it was active in trading with Italy. That owner’s daughter married Dr. Jakob Byschl, who founded the first pharmacy of the regional court in this house. Hence the name of the building, the Alt Apotheke, or “Old Pharmacy”.

There has been a building at what is now the ATLAS Post-hotel at Marienplatz 12 since 1512.

In 1624, it was a tavern, the “Gasthof zur Traube,” and then, for a long time, it was the “Gasthaus zur Post” — or the Garmisch Post Hotel.

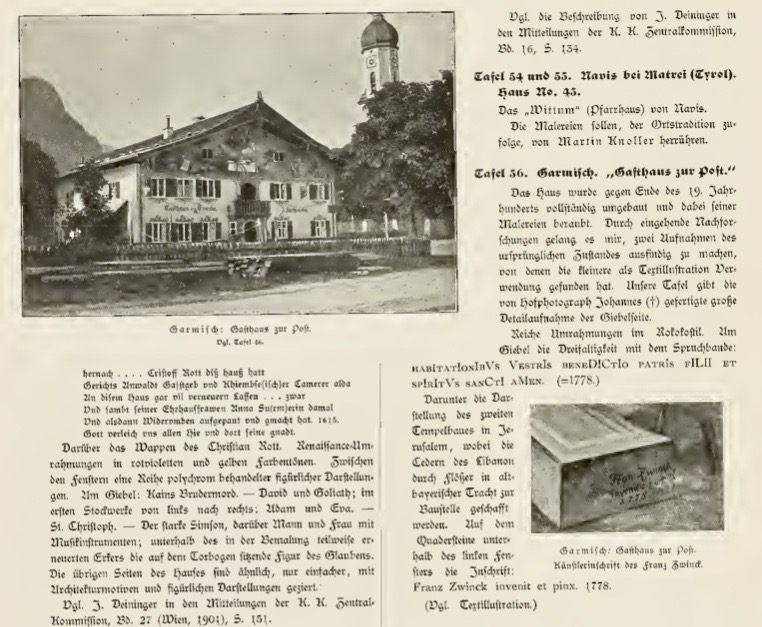

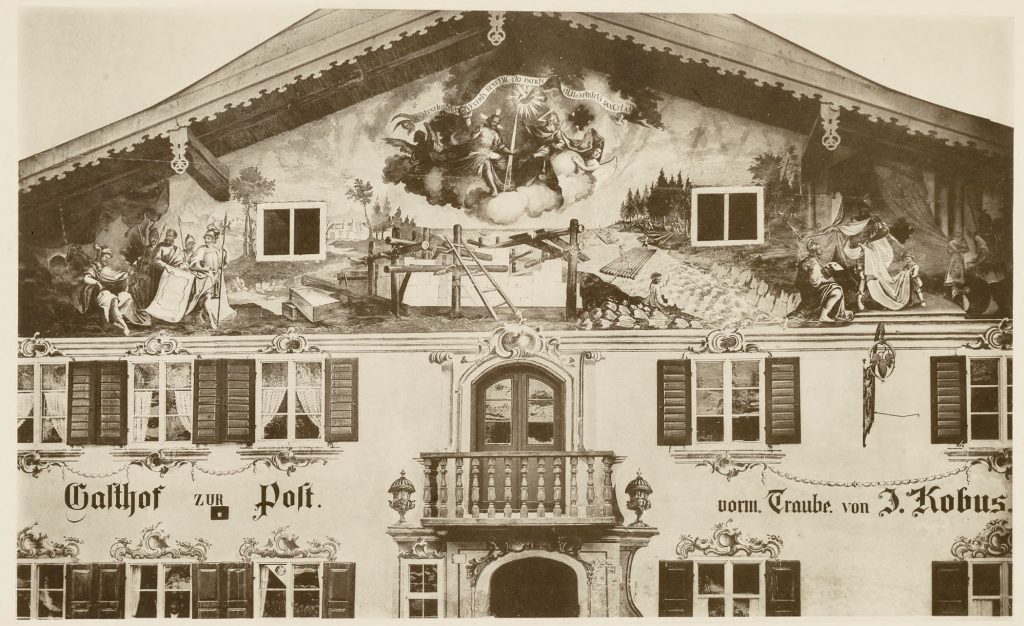

In 1778, the gable on the front of the hotel was painted by none other than “The Lüftlmaler from Oberammergau” himself, Franz Zwinck.

Zwinck’s lüftlmalerei depicted the building of the second temple in Jerusalem, with the cedars of Lebanon being brought to the construction site by rafters in traditional Bavarian costumes.

However, the mural fell victim to an expansion in 1889. The subsequent decorative painting was carried out by a man named Vogelmaier from Partenkirchen, with the design by Richard Godron, the drawing teacher at the Partenkirchen woodcarving school.

In 1891, an innkeeper from Berlin, Heinrich Clausing — credited with having created the Berlin “Weissbier” — took over the hotel, giving the building its name, “Clausing Post Hotel”.

In 1900, author Otto Aufleger noted in his book, Farmhouses from Upper Bavaria and Neighboring Areas in Tyrol, that this “house was completely rebuilt towards the end of the 19th century and was robbed of its paintings.”

Even though this painting can no longer be seen at the Atlas Post Hotel, that very same long lost lüftlmalerei can still be seen about 2 kilometers away, at Rathausplatz 13.

In 1927, Professor Carl Reiser faithfully recreated the mural on the gable of the newly built Werdenfelser Museum there.

Marienplatz 13, the old Dresden Bank.

A lüftlmalerei of the market square from 1860 with Zugspitz massif in the background, painted by Heinrich Bickel some time after 1945.

Marienplatz 14 — called the “Blaues Haus,” or the “Blue House,” after the dominant color of its facade — was once the home of author and historian Ignaz Johann Hibler (1878-1924).

The distinctive facade goes back to its previous owner, master builder and painter Ostler, who decorated this house in the first half of the 19th century.

At Marienplatz 16, above the balcony on the upper floor, you can now see the Coat of Arms for the market town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen and the checkered Bavarian flag, both in decorative cartouches.

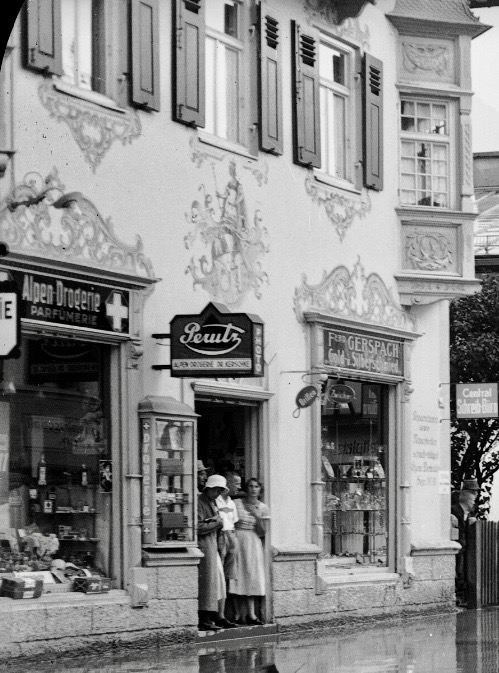

However, in this photo taken by August Beckert some time between 1920 and 1930, you can see that there used to be a completely different lüftlmalerei here, just below the balcony.