Ludwigstraße

53 - 59

“Some things have been lost forever, other things will perhaps be remembered again, and still other things have been lost and found and lost again. There is no way to be sure of any this.“

— Paul Auster, “The Book of Memory,” The Invention of Solitude

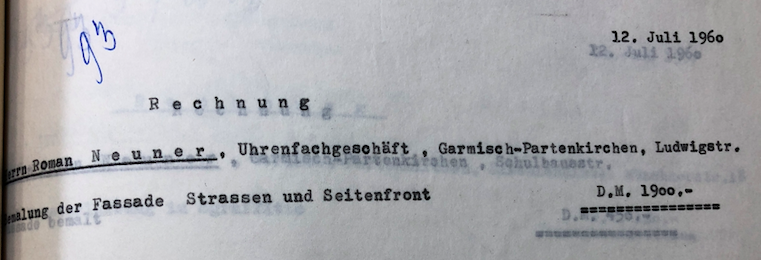

Ludwigstraße 53, former master watchmaker Roman Neuner.

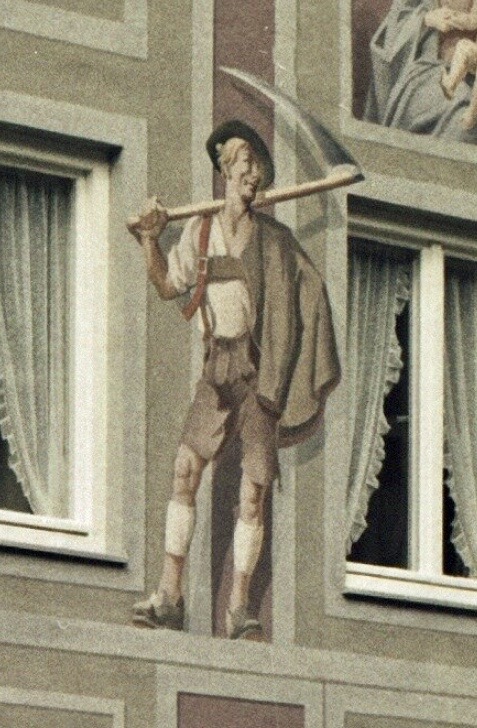

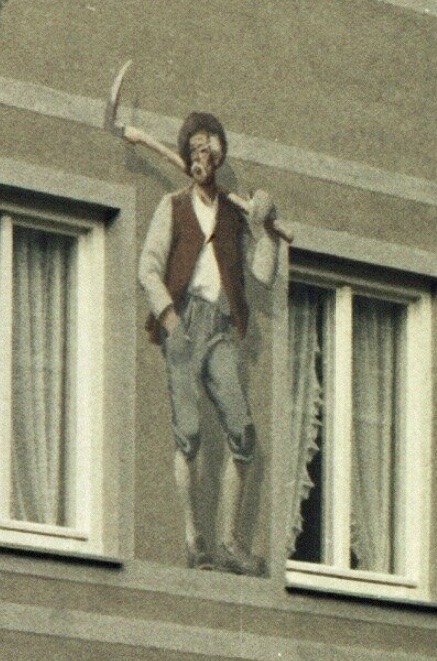

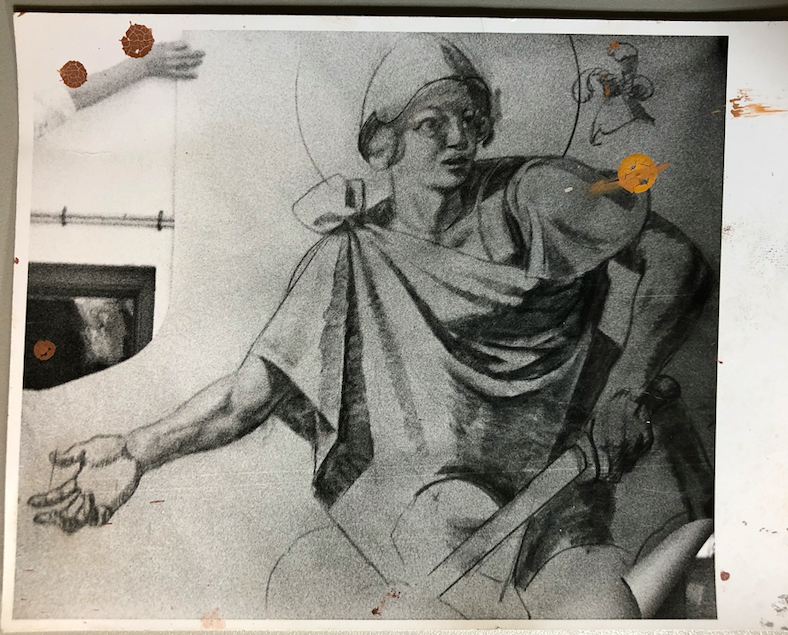

On the front, Lüftlmalerei of a Madonna and Child; a gardener with flowers, farmer with scythe, farmer with fruit basket, raft with raft hook; and on the side, a large panel painting depicting Ludwigstrasse with painted guild sign: “To blacksmith Roman since 1664”; and, above, Saint Romulus, all originally created by Heinrich Bickel in 1960.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archives, you can see a photograph of this building and its lüftlmalerei taken in 1960, here and here.

When you compare the lüftlmalerei in that photo from 1960 and the images on the wall of Ludwigstraße 53 today, you notice that the design of the Fensterumrahmungen around the windows has become more intricate, but, after some later restoration by Sepp Guggemoos, the details of the mural have become stylized — like cartoons of the former figures.

Guggemoos would repurpose and reuse Bickel’s figures when he painted the same images (complete with tree, missing here) at Badgasse 16a.

Ludwigstraße 54.

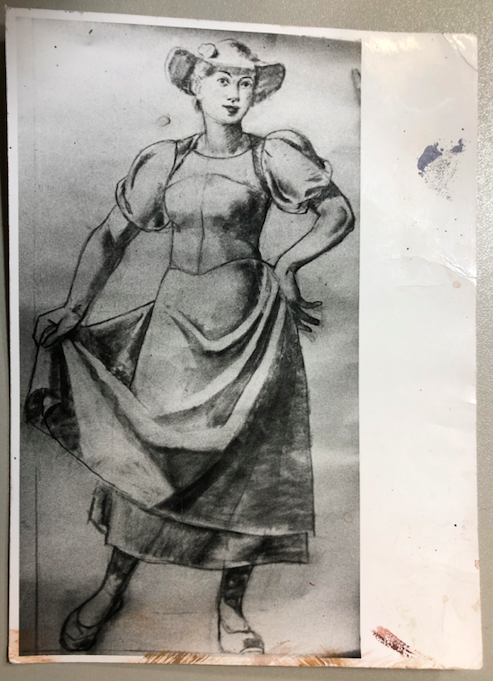

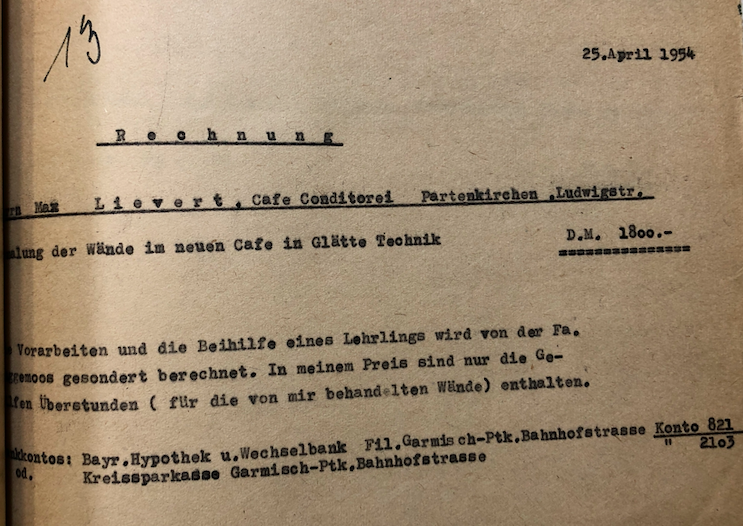

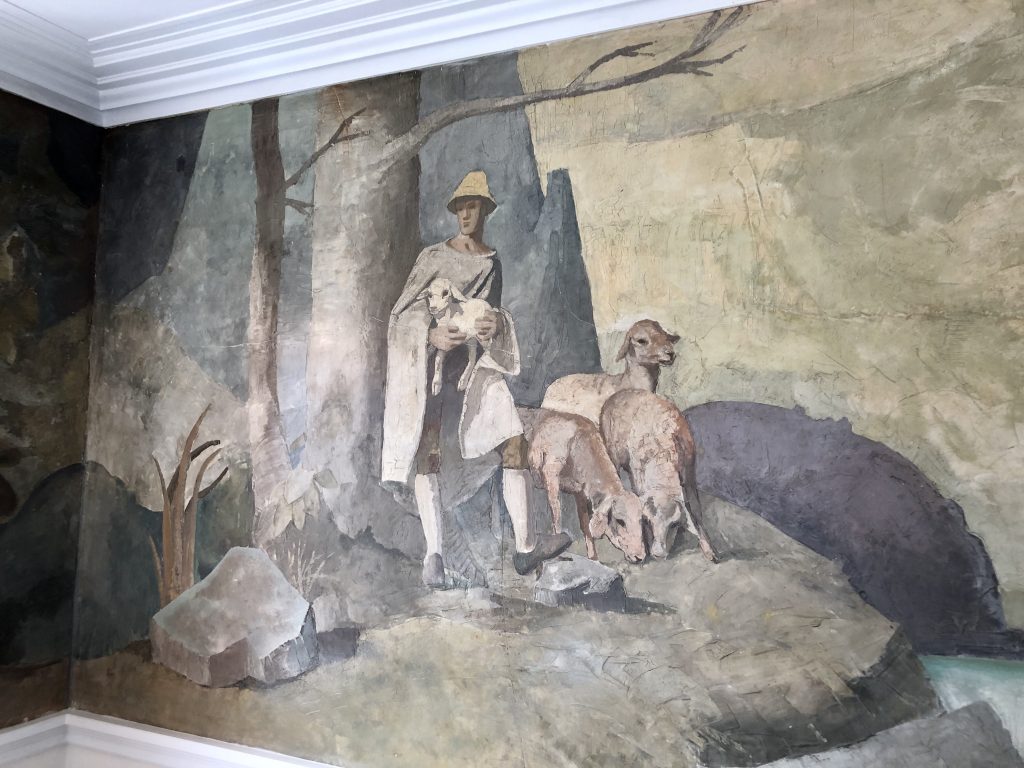

In 1954, when Ludwigstraße 55 was the Konditorei and Cafe Lievert owned by Max Lievert, Heinrich Bickel painted frescoes on the walls inside depicting a mountain landscape with a shepherd with lambs and a dairymaid with cow, a flower seller, and two anglers in a boat on a lake.

Since then, the cafe had closed, the Lievert family sold the building, and — at some point, and for some reason — someone covered the murals Bickel had painted inside.

On September 25, 2012, during a renovation by the Koch, Langhorst, and Rößle lawyers’ office which now occupies the space, the mural was discovered again — discovered poking through a hole in the wall.

The law office chronicles the discovery with photos on their website, which they also have framed and hanging in their lobby.

The mural had wrapped around one of the dining rooms when the building was still a cafe. Now, the figures Bickel painted ring the walls of a separate personal office, a hallway, and a conference room at the law firm.

Attorney Christian Langhorst told me that his colleague, future mayor of Garmisch-Partenkirchen Elisabeth Koch, was present when the mural was found, poking through the plaster of the wall when renovators broke through. It was her 50th birthday, and he said she considered it a beautiful surprise present.

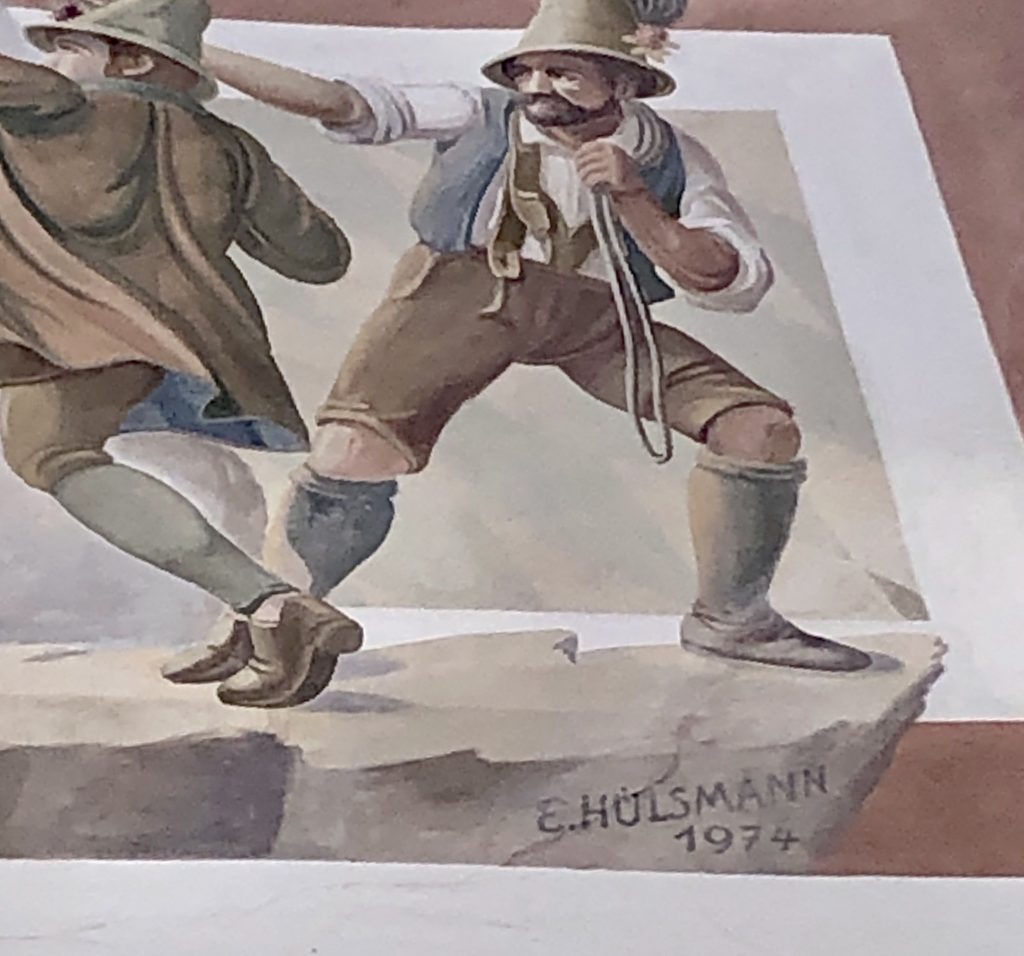

Outside, as this photo from the Bavarian State Archives shows, the lüftlmalerei painted on Ludwigstraße 55 — images of the 1936 Winter Olympics, Emperor Barbarossa kneeling before Duke Heinrich the Lion, and men putting the cross atop the Zugspitze — look very similar today to when they were first painted by Eberhard Hülsmann in 1974.

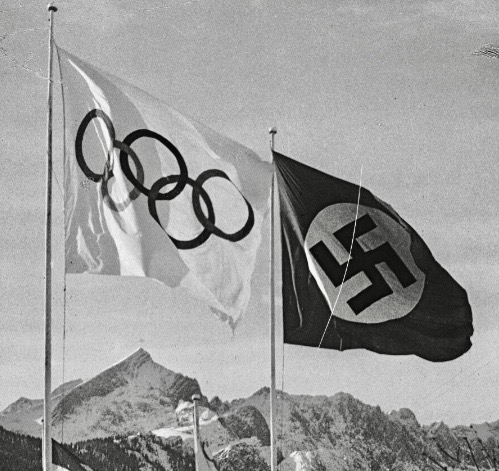

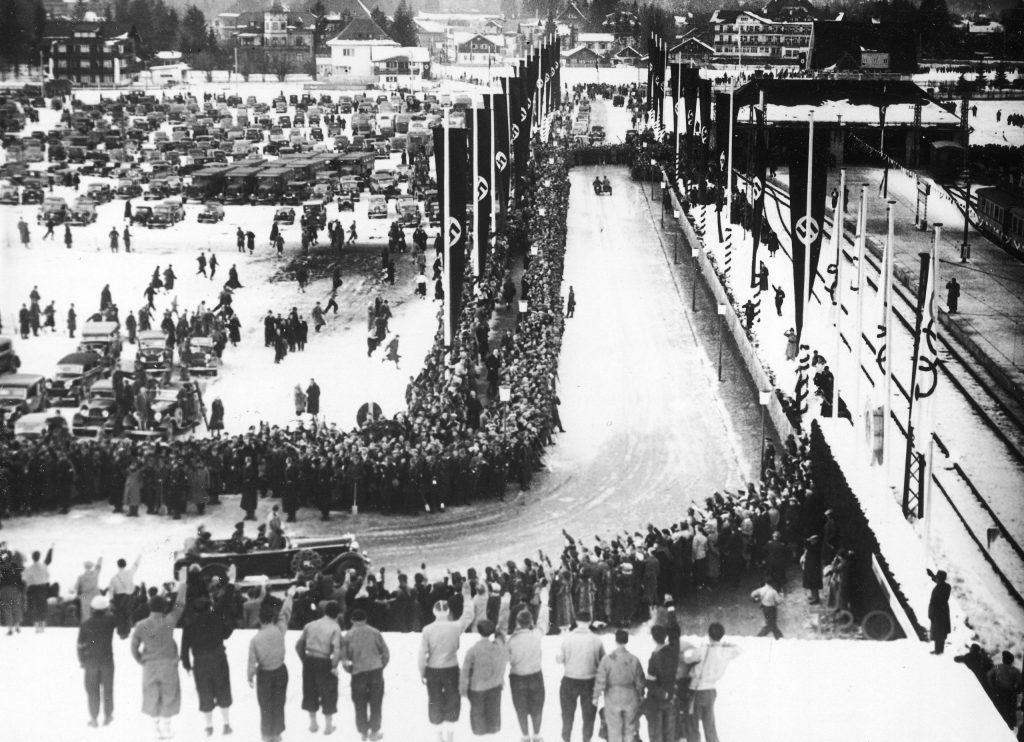

In addition to literally putting the town on the map, the 1936 Olympic Winter Games marked the beginning of mass tourism and cemented Garmisch-Partenkirchen’s reputation as the winter sports travel destination it is today.

According to the Olympic Committee’s 1933 Charter, the goal of the Olympics was to promote the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful and better world through sports and the ideals of mutual understanding. This philosophy was antithetical to Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazis), who came to power in 1933. Rather, the Nazi regime’s platform was based on the doctrine of Aryan racial superiority. Hitler aimed to eliminate Jews, Communists, and other undesirables from Germany, and intended to counter what he saw as the injustices of the post-World War I international orders crippling the country.

While they did not believe in the Olympic ideals, the Nazis were perfect propagandists. Even while planning to remilitarize and annex nearby territories, they saw an opportunity to demonstrate how peaceful and benevolent Germany was — what a friendly dictatorship it could be. Moreover, however, they saw an opportunity to display to the world the strength of the pure and fit New Germany that Joseph Goebbels was promoting as Minister of Propaganda.

The Olympics were the perfect spectacle for, as Susan Sonntag wrote in “Fascinating Fascism” for the February 6, 1974, New York Review of Books, “celebrating a society where the exhibition of physical skill and courage and the victory of the stronger man over the weaker are […] the unifying symbols of the communal culture—where success in fighting is the ‘main aspiration of a man’s life’.”

The Winter Games — in which mainly Caucasian athletes from cold weather-countries compete — were a promising vehicle for the propagandists to provide proof of the Aryan athletic superiority.

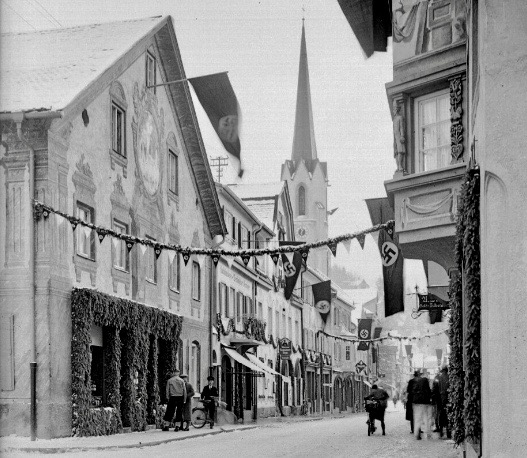

In 1936, the Nazi propaganda machine was able to give the impression abroad that almost all Germans were solidly uncritically loyal to their leader, that domestic success was total, and that onetime dissenters had been themselves overwhelmed by that success. The merged town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen was the very model of the Nazi’s expectations — Swastika flags lined the main streets, there were no protests, no dissent, no local pride to distract from the image of a complete dictatorship.

On March 16, 1935, Hitler formally denounced the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles, reintroduced conscription, and announced a program of rearmament. His soldiers and their weapons were on full display during the Winter Olympics.

Just two days before the Winter Games were to start, on February 4, 1936, Jewish medical student David Frankfurter assassinated the head of the Foreign Section of the Nazi Party in Switzerland, Wilhelm Gustloff, in Davos, Switzerland. Therefore, 6,000 Sturmabteilung (SA) and Schutzstaffel (SS) were present to ensure Hitler’s security when he arrived in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

As Westbrook Pegl wrote in an article, “Arms And Olympics,” in the Washington Post on February 18, 1936, “Soldiers are everywhere in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. All the soldiers wear the Swastika. This gives a strange suggestion of war in the little mountain resort where sportsmen are drawn together in a great demonstration of international friendship. The scene is strongly reminiscent of the zone behind the front when divisions were being rushed to the sector of the next offensive. At home we’ve never found it necessary to mobilize an army for a sport event.”

Three weeks after the Winter Games had ended, on March 7, 1936, German military forces entered the Rhineland, in direct contravention of the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties.

Three years later, in June 1939, believing that no country who hosted the Olympics would dare to start a war, the International Olympic Committee again awarded the 1940 Winter Games to Garmisch-Partenkirchen. A considerable sum of money was spent updating and enlarging the Olympic venue. But a few months after the decision, the Wehrmacht attacked Poland and the Second World War began.

Hitler’s timing between armed incursion and Olympic Games was nothing new. Germany had also previously won the right to host the Olympics back in 1916, but those Games were cancelled due to the outbreak of World War I. As a result of that war, Germany not only lost the right to host, but had actually been banned from competing in the 1920 and 1924 Olympics.

More recently, in 2008, the day before the Beijing Summer Olympics were to start, Vladimir Putin sent armed tanks into Georgia. And in 2014, Russia waited just three days after the Winter Olympics they hosted in Sochi had ended before marching troops into Crimea.

But the 1936 the Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen went exactly as planned, and were a perfect dress rehearsal for the Summer Games in Berlin.

Even the weather played its part.

For weeks leading up to the Winter Games, there had been unseasonably warm weather in Garmisch-Partenkirchen — a phenomenon known locally as “Föhn.”

As Antonia Kleikamp wrote in a February 6, 2016, article for Welt titled “Olympia wäre für Hitler fast zum PR-Desaster geworden,” “The slopes above Partenkirchen around the two large ski jumps were more green than white. At the beginning of February, 1,500 men of the Reichsarbeitsdienst brought snow down from higher altitudes to at least create the appearance of winter. Even worse: The ice for the Olympic ice rink and the bobsled run, both cut from the Riessersee lake with great effort around the cold New Year, thawed massively.”

If the temperatures didn’t drop below freezing, many of the competitions would have been canceled.

However, as if on command, the night before the Winter Games were to begin, as Antonia Kleikamp wrote “A strong low pressure system brought a temperature drop of more than five degrees and a violent snowstorm within hours.”

When Adolf Hitler arrived at the train station on February 6, 1936, at 10.55 a.m., it had begun to snow.

By the time he reached the Olympia Stadion to announce the Winter Games open from the balcony of the Olympiahaus, the snow was 20 centimeters high.

The storm blanketed the 646 athletes (566 men and 80 women) from 28 countries, and some 60,000 spectators from all over the world. As Christopher Hilton wrote in his book, Hitler’s Olympics (2006), all the while, “Hitler, sitting in the grandstand with Goebbels beside him, leant down to receive notebooks, postcards and pieces of paper from those entreating him for his autograph. He smiled broadly.”

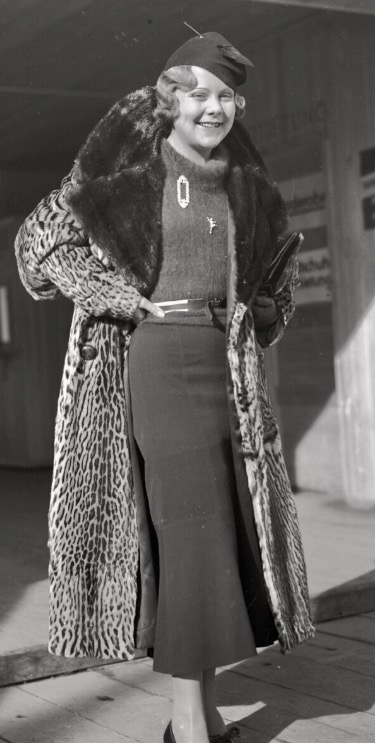

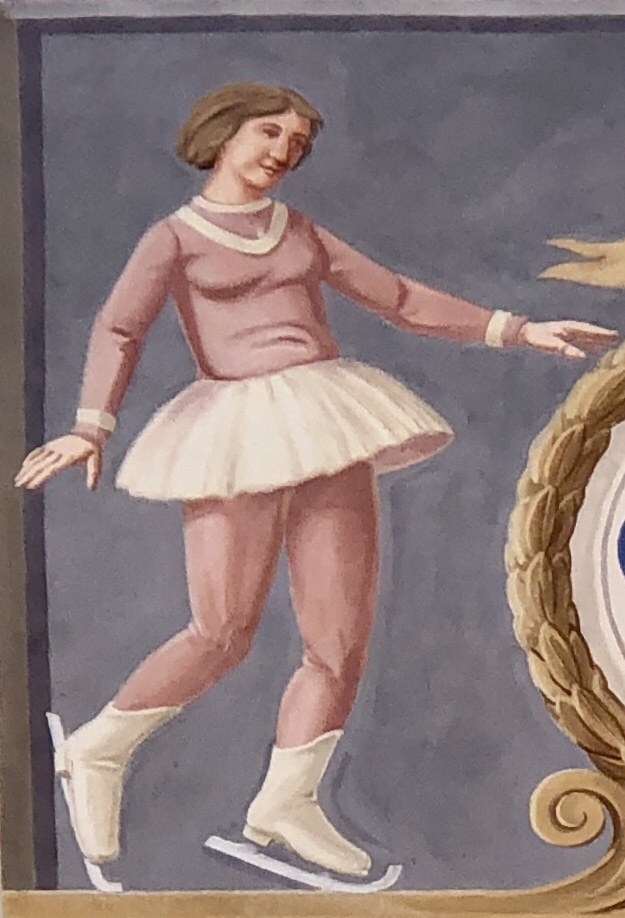

Today, the image of the figure skater on the left in the lüftlmalerei on Ludwigstraße 55 may be that of Norwegian figure skater Sonja Henie.

She can be seen in a similar pose in this photo from the 1936 Olympics by August Beckert from the Bavarian State Archives online.

Sonja Henie won the gold medal for figure skating at the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

It was her fourth Olympics, and her third Olympic win, having won gold in 1932 and in 1928. Henie dominated women’s figure skating like none before or since, having won more consecutive Olympic and World titles than any other ladies’ figure skater to this day. In addition to her Olympic medals, she also won six consecutive European Championships and ten European World Championships, winning her first major competition, the Norwegian Championships, at the tender age of 10.

More striking than her athletic achievements, though, was that, at the time, she was perhaps the most famous person to grace Garmisch-Partenkirchen at the 1936 Winter Games.

As Richard Mandell wrote in his book, The Nazi Olympics (1971):

"Petite, with waving blond hair, round cheeks, button nose, and brave brown eyes, she was cute as anything and her stage presence communicated physical supremacy and aristocratic status. [...] By 1936 she had shed all girlishness. She alone of all the dowdy Norwegian athletes was clad in close-fitting white satin. Sonja wore a snug cap of white feathers, often flourished a fur muff, and bore a corsage--doubtless from an eminent male admirer. Thousands wished to be near her in order to view one of history's great personages. Her public appearances were triumphant processions. her progress from practice or to banquets was inevitably accompanied by the moving hubble-bubble of massed whisperings of her magic name."

He went on to write:

"The two durable heroes of the IVth winter Olympiad were Sonja Henie and Adolf Hitler. Only the undisputed empress of winter and the increasingly secure master of the Third Reich possessed the magic required to fascinate the masses at Garmisch and had the rank of 'stars' in the world at large. The two were demonstratively together a great deal. They fed on each other's staged smiling ('was it his corsage?')--she in clinging white; the Führer with slicked hair and wrapped in a massive black leather overcoat deliberately burnished to a higher sheen than the similar coats of his hangers-on."

After 1936, she took her skating to Hollywood, starring in a number of box-office hits and becoming a United States citizen.

At the height of her fame, Henie made as much as $2 million per year from her movies and touring ice shows, making her one of the wealthiest women in the world in her time.

Given her fame and fortune, stories of her life and career are as numerous as they are contradictory, and many of the details are controversial and contested by her biographers.

One such story, is that after the 1936 Olympic Games, Henie accepted an invitation to lunch with Adolf Hitler at his home in Berchtesgaden. There, Hitler presented Henie with a signed portrait of himself.

This, by itself, was not surprising. As Westbrook Pegler wrote for an article in the Washington Post on February 21, 1936, at the Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Hitler “gave autographs to a hundred or more as willingly as Babe Ruth.”

However, as Jacob Bogage wrote in a February 21, 2018, article for the Washington Post, “When the Nazis invaded Norway in 1940, the Henie family displayed a signed photo of Hitler prominently atop the piano in its Oslo home. The house went unharmed during the fighting.”

Even the origin of a photo of her shaking hands with Hitler is debated. AP Images lists it as taken at an exhibition at the Sports Palace in Berlin on February 22, 1934, while Schirner Sportfoto notes it was taken on February 14, 1936, at the Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

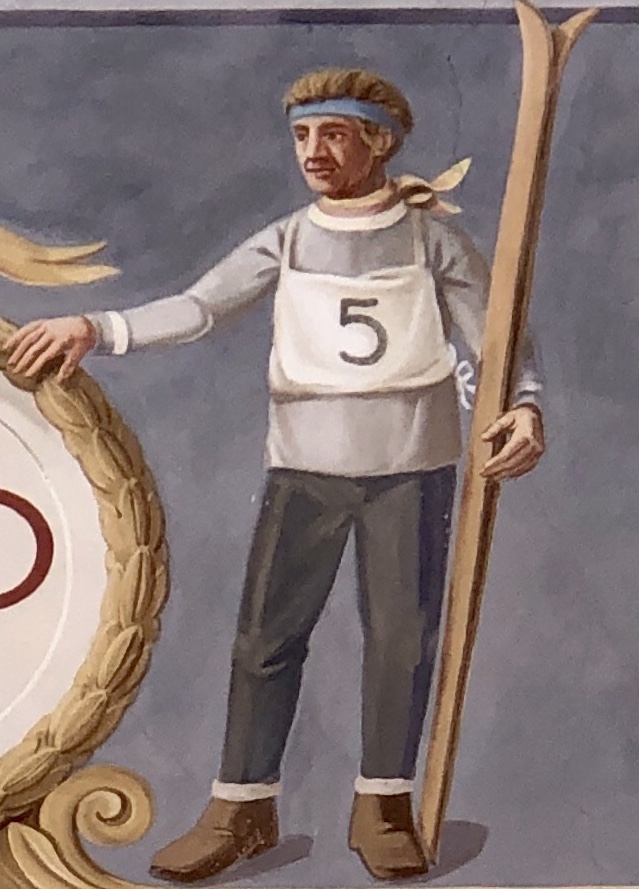

The figure on the right in the lüftlmalerei at Ludwigstraße 55 could be Roman Wörndle.

Born in Partenkirchen in 1913, Roman Wörndle was one of the best competitive skiers in Germany in the 1930s. His family had a shoe store on Ludwigstraße.

Although he didn’t wear the number “5” in the 1936 Olympic Games, an image of Wörndle skiing and wearing a number “5” like the figure in the lüftlmalerei can be seen in this photo from the Polish National Archives online.

The number “5” bib in the lüftlmalerei may reference, not the number he was wearing at the Winter Games, but rather that he took 5th place in slalom and in the combination competitions.

The following year, on February 15, 1937, he won the bronze medal in slalom at the Alpine World Ski Championships in Chamonix.

During the Second World War, he served as a non-commissioned officer in a Wehrmacht ski patrol.

Wörndle died as a soldier fighting on the Eastern Front in early 1942.

Or the skier in the lüftlmalerei could be the female winner of the Alpine skiing gold medal at the 1936 Olympics, Christl Cranz (1914 – 2004).

Käthe Grasegger, from Partenkirchen, won the silver.

Although she did not wear the number “5” bib during the 1936 Olympics, either, Cranz can be seen looking similar to the skier in the lüftlmalerei in this photo by August Beckert from the Bavarian State Archives online.

Between 1934 and 1939, Cranz won 12 World Championships. She literally wrote the book on “Skiing for Women,” Skilauf für die Frau (1935), and the “Tried and Tested Skier and her Equipment,” Erprobtes und Erfahrenes Skilaufer und ihr Gerät (1939).

During the Nazi period, photos of Cranz frequently appeared in magazines, such as Das Deutsche Mädel (“the German Girl”), the monthly publication for the Bund Deutscher Mädel (the League of German Girls”), the female branch of the Hitler Youth, the only legal female youth organization in Germany, with mandatory membership for all girls aged 14 to 18. That magazine emphasized strong and active German women.

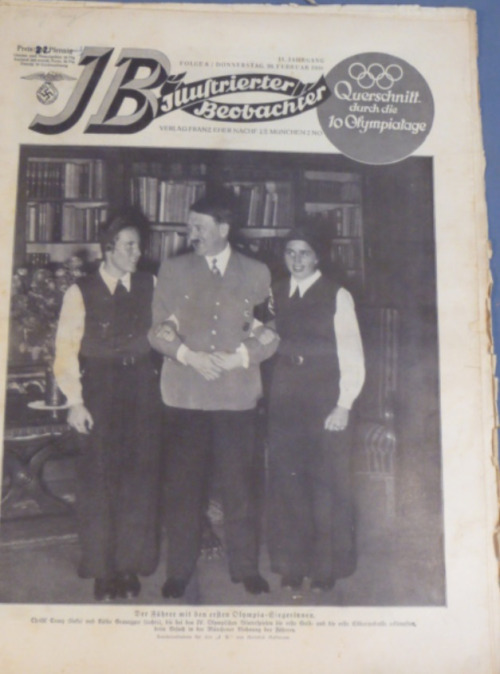

An image of the 1936 Olympic Alpine skiing gold and silver medal winners, Christl Cranz and Käthe Grasegger, posing with Hitler in the Führer’s home appeared in the Illustrierter Beobachter (“Illustrated Observer”), another propaganda magazine published by the German Nazi Party.

Cranz was such an icon at the time, that, as Annette R. Hofmann anecdotally wrote in a footnote to her August 2017 Sport in Society article, “Christl Cranz, Germany’s ski icon of the 1930s: the Nazis’ image of the ideal German woman?”, “Her name was originally spelled Christel. However, due to the many autographs she had to give, she deleted the ‘e’.”

Cranz’s brother Rudi, also a successful member of the national ski team and 1936 Olympic competitor, was drafted into military service in 1941 and died on the Eastern Front.

In 1943, at the age of 27, she married Luftwaffen Major Adolf Borchers. During World War II, she taught physical education at an institute in Freiburg.

After the end of World War II, Cranz-Borchers and her husband were arrested for their collaboration with the Nazi Party, imprisoned, and then committed to a labor camp.

After denazification, she and her husband moved to Steibis in 1947 and founded a ski school there. She became Germany’s first certified female ski instructor, heading the school until 1987. In 1948, Cranz-Borchers was instrumental in founding the Ski Club Steibis-Aach, which she remained a board member of until 1976. In addition to working in the ski school and ski club, she also built a children’s home in Steibis.

In 1991, Cranz-Borchers was inducted into the International Hall of Fame for Women’s Sports, and the German Ski Association appointed her an honorary member.

According to one article, shortly before her 70th birthday, Cranz-Borchers recieved a package in the mail from from France. Inside, her 1936 Olympic gold medal and a note: “I think I found something in a box in Strasbourg that you owned.” The medal had been lost during the war, and finally returned to the Olympic champion after more than 40 years.

Today her medal is part of a Christl Cranz exhibition in the ski museum in Hinterzarten.

As the inscription beneath the lüftlmalerei in the center of the building explains, this is an image depicting the moment, “here on Ludwigstraße in the year 1176” when the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa — depicted here with a red beard — knelt down before Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Bavaria.

Ironically, the faint white and blue checkered field in the background is the flag of Bavaria. However, those colors originally came from the Wittelsbacher family.

As revenge for the embarrassing moment when he asked the Duke of Bavaria for military aid and was refused, in 1180, Emperor Barbarossa declared Heinrich the Lion an outlaw, broke up the Kingdom of Germany into separate fiefs and redrew the borders of the duchies, giving the House of Wittelsbach control of Bavaria for the first time — a dynasty who ruled Bavaria until 1918.

The peak of the Zugspitze mountain, at 2,962 m (or 9,718 ft ) above sea level, is the tallest mountain in the Wetterstein range, and the highest mountain in Germany. It stands just south of the town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, and the border between Germany and Austria runs over its western summit. Three of Germany’s five glaciers are found on the Zugspitze massif: the Höllentalferner, and the Southern and Northern Schneeferner. Beneath the Zugspitze, there are a large number of caves.

Today, the Zugspitze is one of the most popular ski areas in the German Alps. And despite a name that translates to something like “train car falls,” a number of lifts bring thousands of skiers and tourists to the Alpine huts, slopes, and the glacial basin every day.

Given the task of producing a map for the Topographic Atlas of Bavaria, the first climbers to officially reach the top of the Zugspitze, were surveying engineer and lieutenant of the Bavarian army, Josef Naus, his survey assistant, Maier (whose first name is simply absent from all historical records), and mountain guide, Johann Georg Tauschl, on August, 27, 1820.

The authors of Die Strassennamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen, published in 2001, off handedly note that the peak had probably been reached by others before 1820, writing simply “There is a reference to this in 1759.” Local farmers, poachers, and smugglers almost certainly used routes between Garmisch-Partenkirchen and the towns of Tyrol on the other side of the mountain — however, there’s no documentary evidence that any of them had ever actually been to the top.

In 2006, art historian Martina Sepp made headlines when she “found” an old map of the mountain from around 1770. She discovered it while working on digitizing the archives of the Deutschen Alpenvereins (the German Alpine Association). The map noted a route from Garmisch-Partenkirchen through the Reintal “ybers blath ufn Zugspitz“, estimating the trek would take “8 1/2 hours” — which suggested that someone had been to the top of the Zugspitze before Naus and his team.

Tanja Rest explained in a May 17, 2010, article for the Süddeutsche Zeitung titled “Rediscovered Zugspitze Map: ybers blath ufn Zugspitz,” that the map apparently came into the possession of the Munich mountaineer Max Krieger, who published a copy of it as an insert in his 1884 book, Geschichte der Zugspitz-Besteigungen. In the 1930s it was exhibited in the old Alpine Museum in Munich, was lost during the war, and finally reappeared in the possession of the alpine journalist Fritz Schmitt. His estate has been in the archive of the German Alpine Association since 1986.

However, after research, the “map” turned out to be an “inspection card” (“Augenscheinkarte“), made around 1730 in the course of a border dispute between the Werdenfels County and Tyrol. Not a map of a route to the top of the mountain.

As the inscription beneath the lüftlmalerei on Ludwigstraße 55 explains, the image painted there depicts the 28 “citizens of Partenkirchen” who first “erected the cross on the Zugspitze on August 14, 1851,” “under direction of the Royal Bavarian Forest Warden [Karl] Kiendl.”

The driving force behind the expedition was the local parish priest, Christoph Ott, who, various online sources note, once looked upon the face of the Zugspitze and grieved that “the first prince of the Bavarian mountain world raised his head, bald and unadorned into the blue air of the sky, waiting until patriotic exhilaration and courageous determination would take it upon itself to decorate its head with dignity.” (As found on a number of unsourced web sites, his exact words were supposedly: “der erste Fürst der bayerischen Gebirgswelt sein Haupt kahl und schmucklos in die blauen Lüfte des Himmels emporhebt, wartend, bis patriotisches Hochgefühl und muthvolle Entschlossenheit es über sich nehmen würden, auch sein Haupt würdevoll zu schmücken.”)

As a result of his efforts, “at a cost 610 Gulden and 37 Kreuzer,” the 28-piece, 14 foot high, gilded iron cross stood on the West Summit.

After 37 years, the cross had to be taken down after suffering numerous lightning strikes; its support brackets were also badly damaged. In the winter of 1881–1882 it was brought down and repaired. On August 25, 1882, seven mountain guides and 15 bearers took the cross back to the top. Because an accommodation shed had been built on the West Summit, the team placed the cross on the East Summit. There it remained for about 111 years, until it was removed again on August 18, 1993. This time the damage was not only caused by the weather, but also by American soldiers who used the cross as target practice in 1945, at the end of the Second World War. That cross is now on display in the Werdenfels Museum.

A replica was this time carried by train to the Zugspitzplatt, from where it was flown to the summit by helicopter. The new cross has a height of 4.88 meters. It was renovated and regilded in 2009 for 15,000 euros and, April 22, 2009, it has stood on the top of the East summit of the Zugspitze.

As American travel writer Rick Steves wrote:

"[Today] it's easy to actually 'summit' the Zugspitze from the viewing platforms, as there are steps and handholds all they way to the cross. Or you can just feed the birds from the lounge chairs of the highest beer garden in Germany. The yellow-beak ravens — who get chummy with anyone who shares some pretzels — seem to enjoy the views here as much as the humans. While the Germans glory in the Zugspitze, their nation's highest point, their neighbors are less impressed: There are many higher mountains in Austria."

The windows at Ludwigstraße 56, the old bakery “zum Langer-Beck, 1466,” are ornately framed.

According to the Bavarian monument preservation list, the Denkmalliste, Heinrich Bickel crafted these stucco window frames with lüftlmalerei inside some time between 1925 and 1935. The wingless putti inside the plaster cartouches work in all the positions required to bake bread.

In the center, the double-headed eagle from the imperial banner of the Holy Roman Empire from 1430 till 1806.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archives, you can see Franz Kölbl photograph of this building taken in 1963, here.

Ludwigstraße 57.

According to the Werdenfelser Hof’s website, the history of Ludwigstraße 58 goes back to the 16th century. At that time, the inn was already operating in as a brewery. While the brewery is now gone, the current restaurant and inn has been owned by the Augustiner Bräu Munich brewing company since 1935.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archives, you can see a photo of this building and its original Fensterumrahmungen lüftlmalerei as they looked in in 1923 by August Beckert, and today’s lüftlmalerei as they looked in 1956-1966 in this photo taken by Franz Kölbl.

According to pamphlets printed by the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Tourist Office, Ludwigstraße 59 was formerly a jewelry store whose owner, Anton Simon, was known as “Silberer (‘Silver’) Toni”. Hence its name, the “Silberer-Haus.”

Online, at the Bavarian State Archives, you can see August Beckert’s photograph of this building taken in 1932.

As you can just make out in that photo, the details in the images above the windows are similar, but not the same today as they were in 1932.