- Adam, Peter, & Anton Jocher. Die Strassennamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Adam Verlag, 2001, p. 110: "Es steht zu vermuten, daß die Straße zum Gedenken an König Ludwig II benannt wurde. Übernachtete er doch oft im nahe gelegenen Schweizerhaus (Sonnenbergstraße) und durchfuhr nächtens den Markt auf seinem Weg zum Schachen."

- von Schaden, Adolph. Taschenbuch für Reisende durch Bayerns und Tyrols hochlande, dann durch Berchtesgadens und Salzburgs Gefilde, nebst Beschreibungen Hohenschwangaus, Casteins, des Salzkammergutes und Bodensees. Josephlindauer’sche Buchhandlung, München, 1834, p. 11: "Dieser Markt, 28 Poststunden von München entfernt und allgemeinem Borgeben nach das alte Parthanum oder Partenum der Römer, ist eine Poststation und zählt in 259 Häusern mehr als tausend Einwohner."

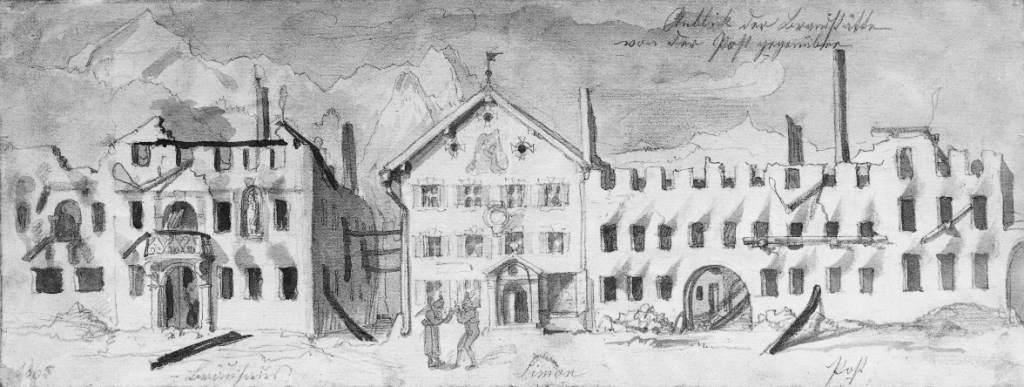

Lüftlmalerei

A street by street guide to the fresco and facade paintings in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district