Ludwigstraße

36 - 52

“Myths which are believed in tend to become true“

— George Orwell, “The English People“

Ludwigstraße 36, “Haus Simon,” is covered in cryptic lüftlmalerei by artist Sebastian Pfeffer.

For decades now, the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Tourist Office has been publishing pamphlets saying that the owner of the house “was fascinated by Greek mythology”, and that the mural painted on the front of this building was an image of “God sat on a throne on top of the animal symbols for fire, water, air and earth”.

This, however, is not so.

Altogether, the separate motifs and symbols are a blend of Astrology, the Bible, Renaissance art, and Wagnerian opera.

In the center at the top, God sits on a throne beside Renaissance representations of the Four Evangelists, authors of the four Gospels of the New Testament of the Bible: Matthew, a Winged Man; Mark, a Winged Lion; Luke, a Winged Ox; and John, an Eagle. These symbols come from the creatures envisioned in the Book of Ezekiel and in the Book of Revelation.

This particular lüftlmalerei is reminiscent of Rafael‘s The Vision of Ezekiel painted in 1518.

Then I looked, and behold, a whirlwind was coming out of the north, a great cloud with raging fire engulfing itself; and brightness was all around it and radiating out of its midst like the color of amber, out of the midst of the fire. Also from within it came the likeness of four living creatures. And this was their appearance: they had the likeness of a man. Each one had four faces, and each one had four wings. Their legs were straight, and the soles of their feet were like the soles of calves’ feet. They sparkled like the color of burnished bronze. The hands of a man were under their wings on their four sides; and each of the four had faces and wings. Their wings touched one another. The creatures did not turn when they went, but each one went straight forward. As for the likeness of their faces, each had the face of a man; each of the four had the face of a lion on the right side, each of the four had the face of an ox on the left side, and each of the four had the face of an eagle.

Ezekiel 1:3-10

And before the throne there was a sea of glass like unto crystal: and in the midst of the throne, and round about the throne, were four beasts full of eyes before and behind. And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast like a calf, and the third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle.

Revelations 4:6-7

When the symbols of the Four Evangelists appear together like this, it is called a “Tetramorph,” common in church frescoes and mural paintings.

In the corner on the right above, a six-winged angel intertwined with the wheels of God’s throne. These wheels were “each composed of two nested wheels”, that move in concert with the angels, having “eyes all over, front and back”.

Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly. And one cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the LORD of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory.

Isaiah 6:2-3

Each appeared to be made like a wheel intersecting a wheel. As they moved, they would go in any one of the four directions the creatures faced; the wheels did not change direction as the creatures went. Their rims were high and awesome, and all four rims were full of eyes all around.

Ezekiel 1:15-21

And the four beasts had each of them six wings about him; and they were full of eyes within: and they rest not day and night, saying, Holy, holy, holy, Lord God Almighty, which was, and is, and is to come. And when those beasts give glory and honour and thanks to him that sat on the throne, who liveth for ever and ever.

Revelations 4:8-9

In the bottom center, a medallion ringed with the symbols of the Zodiac, surrounding an image of Aquarius, “the Water Bearer.”

Traditionally, Aquarius is associated with technology, freedom, humanitarianism, idealism, and modernization. The Age of Aquarius, in astrology, is either the current or forthcoming astrological age, depending on the method of calculation. Astrologers maintain that an astrological age is a product of the earth’s slow precessional rotation and lasts for 2,160 years, on average (25,920-year period of precession / 12 zodiac signs = 2,160 years).

To the left and right of the Zodiac, the presentation of a choice:

To God’s right (our left as we look at the mural), Peace and Prosperity; while to His left (always the sinister side), Destruction.

On the bottom left of the facade, we see an angel with a flaming sword set to guard the Tree of Life after Adam and Eve were cast out of the Garden of Eden.

Then the LORD God said, “Behold, the man has become like one of Us, to know good and evil. And now, lest he put out his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever” — therefore the LORD God sent him out of the garden of Eden to till the ground from which he was taken. So He drove out the man; and He placed cherubim at the east of the garden of Eden, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way to the tree of life.

Genesis 3:22-24

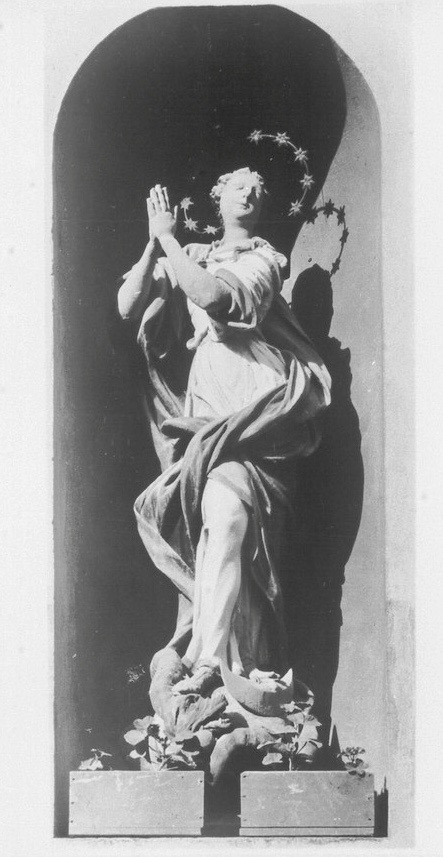

The angel stands on the crescent moon while holding a white lily — symbols often associated with the Patrona Bavariae — which is itself derived from a scene described in the Book of Revelation 12:1, that a woman stood with the “moon under her feet.”

By standing on the moon, this angel shows that he is more powerful than the elements of darkness. However, in Christian iconography the crescent moon under the Madonna’s feet is also a symbol of her perpetual virginity — a purity further exemplified by the white flowers.

The image of incense being burned in a censor, called a thurible, in Renaissance art usually represents the prayers of saints.

Left of the angel, images depicting science — a compass, a globe, and a gear — and a putto raising a “triregnum,” the Papal Tiara — a symbol for the Catholic Church — with an iron cross medal on a ribbon around his neck, and another crown beneath the moon the signifying the German Empire.

On the bottom right, images from the Book of Revelation (12:7-9) describing the war in Heaven in which Archangel Michael defeats Satan, casting him to earth with the fallen angels — here signified by falling, wingless putti — where “that ancient serpent called the Devil and Satan” still tries to lead the world astray.

And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.

Revelations 12:7-9

The cast-out angels appear to be in the darkness of a shadow. Physical darkness often symbolizes spiritual darkness — the absence of God’s love. The Devil, after all, was the “Prince of Darkness.”

Another duality in the lüftlmalerei is that, while there is a symbol of the moon is on the left — underfoot and conquered — at the right, there is a symbol of a smiling sun on the Archangel’s shield.

Also on the angel’s shield, “thymus” is written in Greek-looking letters.

While Plato described “thymos” as the part of the soul comprising pride, indignation, shame, and the need for recognition, the actual Greek word (spelt “θυμός”) literally means “anger.”

(In other artistic depictions, this archangel’s shield reads: “Quis ut Deus“, a Latin phrase meaning “Who is like God?”, a literal translation of the name “Michael,” from the Hebrew: “מִיכָאֵל,” transliterated “Micha’el” or “Mîkhā’ēl”.)

To the far right, images suggesting nuclear war — a nuclear reactor’s cooling tower, a mushroom cloud, and a missile — followed by a wave, reminiscent of the Biblical flood that wiped out all life on earth.

Above each window, at the top of the painted frame, a Germanic Rune — ancient symbols depicting the first written language in Germany.

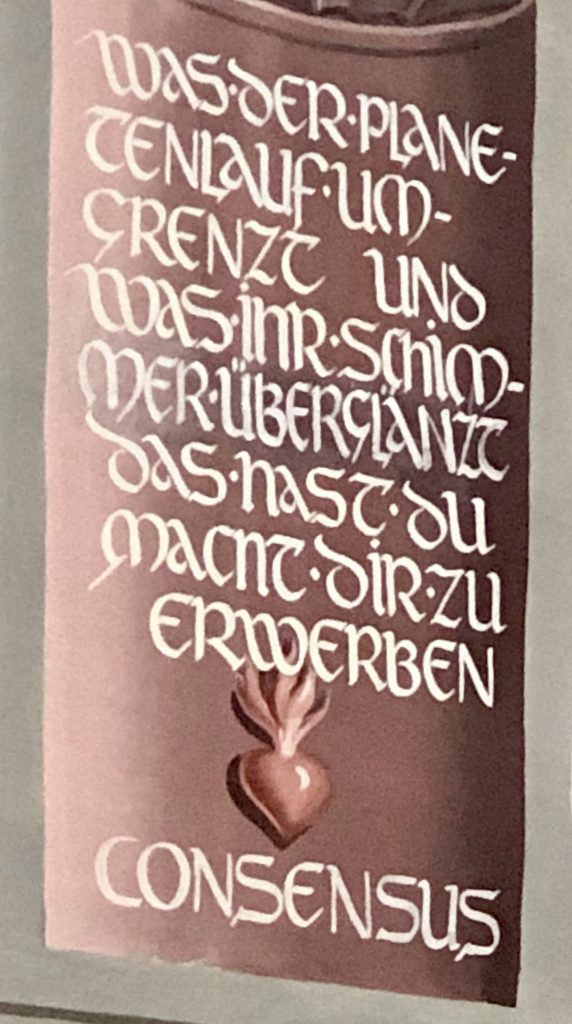

In the very center, an inscription, a line from the epic poem Parzival, about King Arthur and the search for the Holy Grail, written by Wolfram von Eschenbach around 1207:

„Was der Planetenlauf umgrenzt und was ihr Schimmer überglänzt, das hast Du Macht, dir zu erwerben.“

Which translates, roughly, to: “What defines the course of the planet and what makes its shine shimmer, you have the power to acquire.”

Beneath the quote, an image of a flaming heart — a symbol in Renaissance art depicting religious passion.

Bavarian King Ludwig II was inspired by the poem, and Singers’ Hall in his Neuschwanstein Castle is decorated with tapestries and paintings depicting the story. He was also patron to the composer Richard Wagner, and encouraged him to create the opera, Parsifal, based upon the poem.

Rather than the Holy Grail, however, the inscription here suggests a search for something else, no less magical or mythical: “Consensus.”

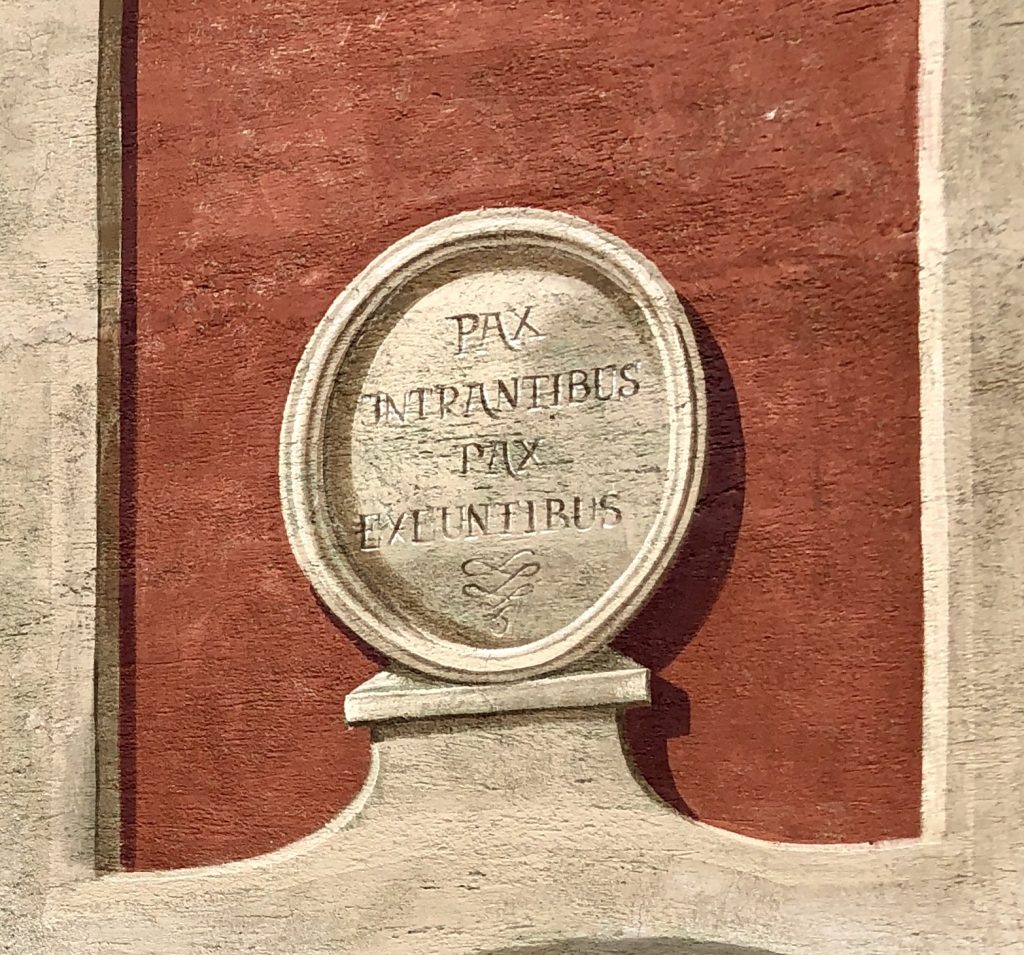

Around the corner, two more inscriptions:

“Opfre täglich Gott vor allen Im gebete Dank und Greis Denner sicht mit Wohlgefallen nuf der Arbeits Mannes Fleis,” and “Handwerk ist Fäbigkeit. Die der Mensch wokänden hält, als von der Gottheit infamgene Gabe.“

Or: “Offer daily to God in front of everyone. Praying thanks and old man gives with good pleasure for the working man’s work,” and “Handicraft is liveliness. Which man holds as a gift infamous from the deity.”

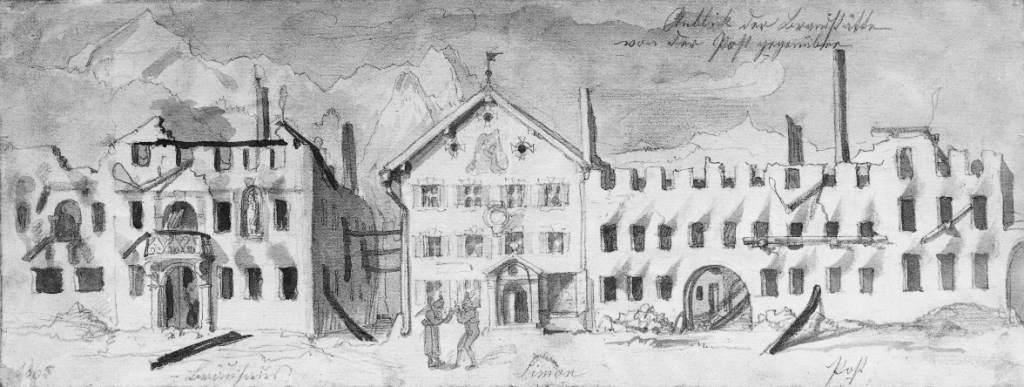

On the gable above Ludwigstraße 37, there is a lüftlmalerei of dancing Schäfflern (“coopers,” or “barrel makers”), with the checkered field of the Bavarian flag behind them.

Today, this building is home to the Chocolaterie Amelie, but this lüftlmalerei is from the time when this was the “Gasthof zum Melber,” renowned for its food and its beautiful garden behind the house.

The Gasthof zum Melber was also famous for its lavish “Melberfest,” which included a stage for dancers of the Schuhplattler and the Schäfflertanz.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archive, you can see a photo of this building when it was still the Gasthof zum Melber but before the lüftlmalerei was painted, and another photo of it soon after it was added.

It is said that the Schäfflern have danced in Munich every seven years since 1517.

In the 1500s, because of the sheer number of breweries in Munich, one of the most prominent trade guilds in the city were the barrel makers.

Legend has it, that in 1517, after an outbreak of the plague, when people were still hiding and shuttered in their homes, it was the Schäffler guild who first took to the streets and danced. At the sound of their music, the windows opened, and at the sight of their dancing, the frightened people finally dared to leave their homes.

In gratitude for the happy end of the plague, the Schäfflern vowed to continue to perform every seven years.

To this day, the Schäffler only dance every seven years, and — even then — only during Fasching (German Carnival), between January 6 (Epiphany or Three Kings’ Day) and Shrove Tuesday (before the start of Lent).

Although seven is considered a lucky number and, apocryphally, the plague came every seven years, exactly why the dance is only performed every seven years is not actually clear.

The Schäfflertanz is so much a part of Munich’s history, that figures representing Schäfflern dance around the famous Glockenspiel in the tower balcony of the New Town Hall.

Since it was completed in 1908, 32 life-sized figures representing two major events in Munich’s history twirl on two levels, accompanied by the ringing of 43 bells, every day at 11:00 AM and noon.

On the level above, the wedding of Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria, to Renata of Lorraine in 1568. In honor of the happy day, life-sized knights on horseback joust. (Certain locals are quick to point out to gawking tourists that the Bavarian knight has never once lost.)

Below them, the Schäffler dance.

In addition to the knights and the dancers, the Münchner Kindl (the symbol of the city’s coat of arms) and the Friedensengel (the “Angel of Peace”) also make an appearance during the almost 12-minute-long mechanical spectacle

However, there was no plague outbreak in Munich in 1517. Moreover, the first time the Schäfflertanz is mentioned in the archives of the city of Munich is in 1702. And the first recorded mention of the dance being performed every seven years is in 1760.

While the Schäffler dance has been a tradition in Munich for hundreds of years, the myth of the dance’s origin emerged sometime around 1830, when the dance first began to spread to the rest of Bavaria.

Andreas Lidl is said to have brought the dance to Partenkirchen in 1834.

The dance evolved into its present form with the establishment of Schäfflertanz associations in 1871, and — as symbol of how seriously the Schäfflern took their dancing — until 1963, only unmarried men who actually belonged to the barrel making guild were allowed to perform.

Today, with fewer barrels being made and fewer men learning the trade, anyone who is interested can become a member of their local Schäfflertanz association.

While the lüftlmalerei of the dancers at Ludwigstraße 37 today has been preserved, on the corner of the gable beside them used to be an image of the Münchner Kindl as a boy holding a pretzel, which has since been lost, as you can see in this photo from the Bavarian State Archives from August Beckert in 1950.

Also, the lüftlmalerei around the door has changed and has since been lost, as you can see in this photo from Franz Kölbl in 1975.

Today, Schäffler dancers dress in red coats, black caps, white stockings, and wear a leather apron. The group consists of 25 men — 20 dancers, two Reifenschwinger (hoop twirlers), two Kasperln (clowns), and one Fähnrich (flag-bearer).

They perform seven different dances, many of them very intricate, while carrying ash wood bows wrapped green with yew twigs, and ultimately, over the course of the dance, they put together a barrel from separate staves to stand on.

The Reifenschwinger has the most difficult job. He holds a hoop with an indentation on the inside of the rim where he balances a small glass filled with Schnaps. Standing on the barrel in the middle of the circle of the dancers, he twirls the hoop with the full glass inside it over his head and between his legs, being careful, of course, not to spill a single drop.

At the finale of this seemingly impossible stunt, he drinks the Schnaps and, without looking, tosses the empty glass over his shoulder, where one of the clowns catches it in his cap.

The Reifenschwinger in the lüftlmalerei at Ludwigstraße 37 is twirling a hoop while balancing, not one, but three glasses inside it.

Also, at some point when the image was renovated, some artist added a step to the dance — the Reifenschwinger’s feet were together in 1950, but by 1975, he had kicked one foot out.

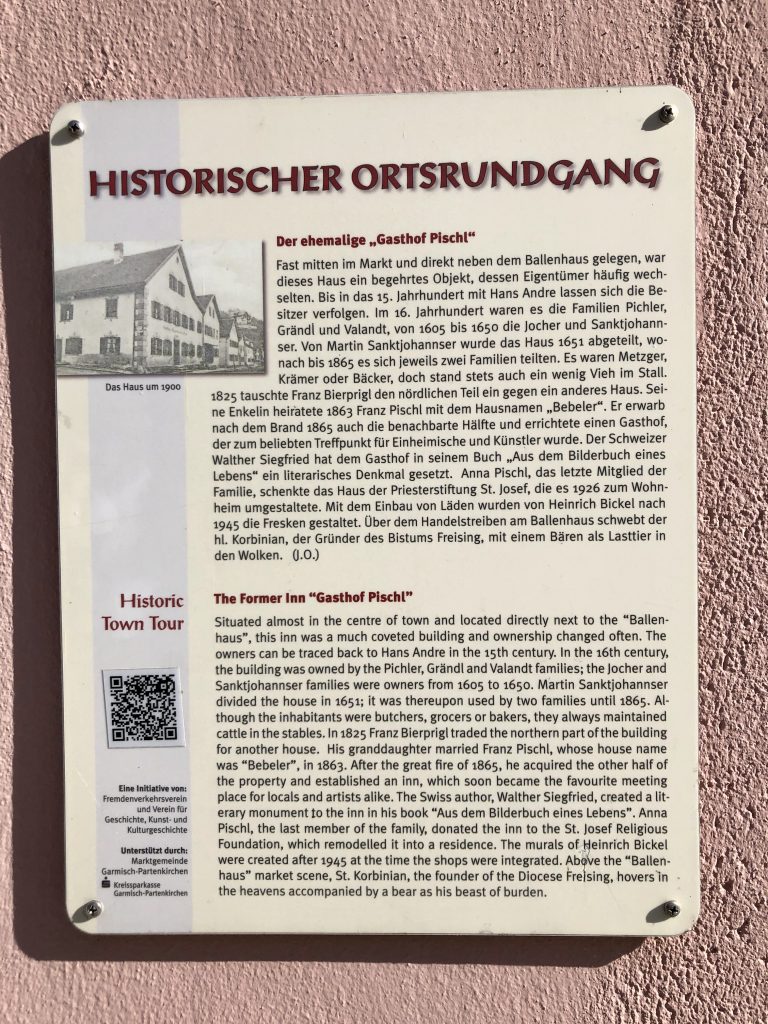

Ludwigstraße 38.

According to the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Tourist Office plaque on the wall outside, this building has been traced back to the 15th Century.

It was an Inn after the 1865 fire, and renovated into its current form some time after 1945.

On the front, a lüftlmalerei of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, and, around the corner, Saint Corbinian — patron saint of merchants, carters, and mountain farmers — both painted by Heinrich Bickel after 1945 and restored by Tobias Pieper in 2014.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archive, you can see a photograph of this building by August Beckert some time between 1946 and 1956, here.

However, Becket’s photograph has clearly been altered, as the mountain range in the background is on the wrong side of this building.

Around the corner, a mural of Saint Corbinian, beside his iconic bear, makes the sign of benediction, blessing the merchants and porters below from the clouds above.

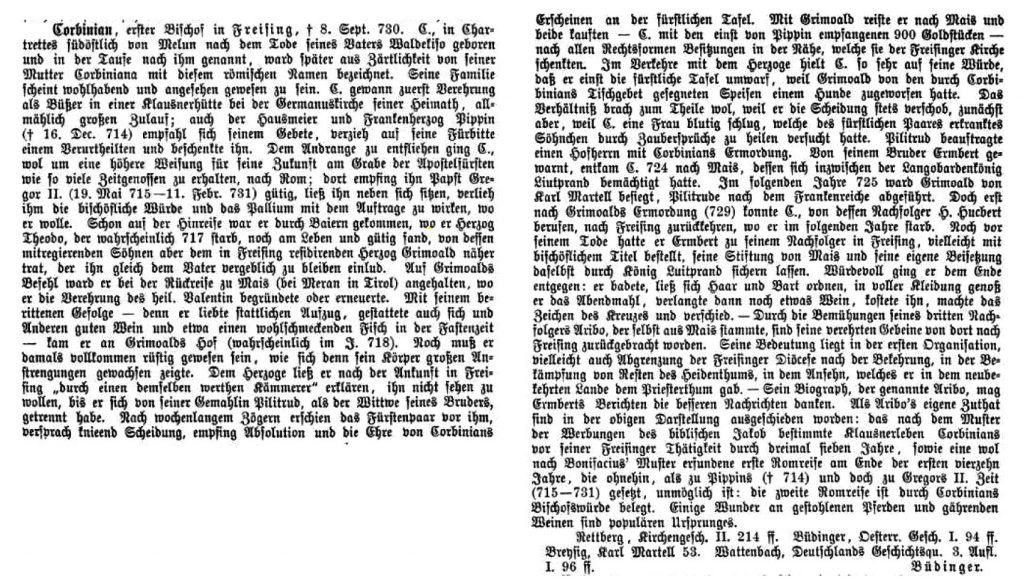

Saint Corbinian (circa 670 AD – circa 730 AD) was a missionary in what is now France, Switzerland, Bavaria, and northern Italy, and is considered the first bishop of Freising. The Benedictine abbey of Freising was founded by Saint Corbinian around 723–730, although it wasn’t until 739 that the Freising diocese was established by Saint Boniface.

Around 1300, Freising diocese bishops bought the County of Werdenfels, split it into three administrated areas — the towns of Mittenwald, Garmisch, and Partenkirchen — and ruled those areas as the Prince-Bishopric of Freising until 1802.

And it all began with Corbinian…

According to the Vita Corbiniani written by Bishop Arbeo, Corbinian was born into a wealthy family near what is now Saint-Germain-lès-Arpajon, in France, around the year 670 AD. At a very early age, he decided to abandon society and live as a hermit — to pray and worship in solitude. During his fourteen years in isolation, he developed a reputation which attracted acolytes and pilgrims. Eventually, he was visited by nobles who gave him rich gifts and asked him to pray for them.

The numerous visitors finally annoyed him into deciding to make a pilgrimage to Rome to beg the pope to allow him a private place to worship in peace. Pope Gregory II, however, did the exact opposite, and admonished him to use his talents to evangelize in pagan Tyrol.

According to the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, published by the Historical Commission of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences in 1876, Corbinian probably first arrived in Freising in 718 at the request of Duke Grimoald of Bavaria.

It also notes that “Some miracles about stolen horses and fermenting wines are popular.”

Several such miracles have to do with the Benedictine monastery Corbinian founded on the Weihenstephan mountain overlooking the town of Freising.

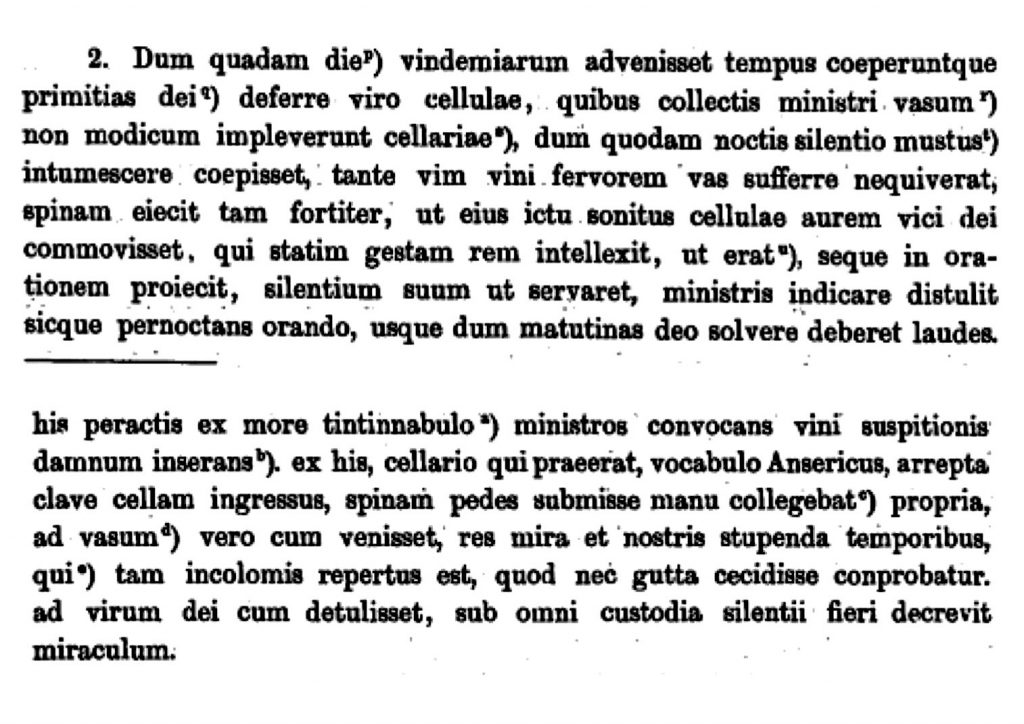

To paraphrase from Franz Xaver Sulzbeck’s Leben des heiligen Corbinian ersten Bischofs zu Freising (1843) and Sigmund von Riezler’s Vita Corbiniani in der ursprünglichen Fassung (1889), one day the monastery was given a barrel of young wine, which the monks placed in the cellar. Since the wine was still fermenting, that night, the build up of carbon dioxide burst the bung out of the barrel with a loud explosion. Corbinian, who was praying at the time, heard the sound, but commanded that nothing — especially not an exploding bunghole — was allowed to disturb him from his prayer. The next morning, the monks found that, despite the barrel having been uncorked all night, miraculously, none of the wine had leaked out.

Another legend has it that the monks there struggled every day carrying water up the mountain from a stream below. One day, Corbinian rammed his staff into the rocky ground near their abbey, causing water to miraculously gush forth.

That fountain, the Korbiniansbrünnlein, is still flowing to this day, and that monastery has since become the Weihenstaphaner Brewery, which bills itself as “the world’s oldest brewery”, as a document from the year 768 refers to a hop garden in the area paying a tithe to the monastery, and a brewery license was first issued by the city administrators in the year 1040.

Miracles aside, the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie goes on to explain that Saint Corbinian made an enemy of his hosts, Duke Grimoald and his wife, Pilitrud, by first denouncing them and accusing the duke of incest for marrying his own brother’s widow. “After weeks of hesitation, the couple appeared before him, kneeling, and promised to divorce” (and also donating “900 gold pieces” to his church). Some time after that, Corbinian “overturned the princely table”, “jumping up, throwing the table over with his foot, making the silver cups roll”, “because Grimoald had thrown food to a dog from the table blessed by Corbinian’s prayer.” The final straw, though, came when Corbinian “struck bloody” a woman who tried to cure the sick son of the Duke and Pilitrud “by spells.”

Pilitrud then commissioned a lord to assassinate Corbinian.

Warned by his brother, Ermbert, that the ruling couple planned to have him killed, in 724, Corbinian fled south across the Alps, to the small town of Kuens in Tyrol.

The very next year, in 725, Grimoald was defeated by Frankish ruler Charles “the Hammer” Martel, and Pilitrude was taken away with the Franks. (According to Bishop Arbeo’s Vita Corbiniani, Pilitrud subsequently lost all of her power and dignity and had to drive a donkey cart to Italy, where she died.) It was only after Grimoald’s murder, in 729, that Corbinian was able to return to Freising, where he died the following year, in 730.

Before his death, he named his brother Ermbert his successor bishop in Freising, and arranged his own funeral.

According to the the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, at the very end of his life, Corbinian “bathed, had his hair and beard arranged, in full dress he enjoyed the sacrament, then asked for some more wine, tasted it, made the sign of the cross, and passed away.”

He was buried in Kuens. Later, however, Bishop Arbeo had his remains transferred and entombed in the Freising Cathedral.

Hundreds of years after his death, a cult of Corbinian formed, and pilgrims came to the tomb of the saint who, it was said, could still perform miracles.

One of the myths that soon developed about the saint, was that, while sleeping one night on his way to Rome, a bear crept out of the woods and attacked Corbinian’s pack horse. Corbinian awoke to find it still gnawing on his horse’s carcass, with his pack strewn across the ground. The saint then commanded the bear to carry his load in his horse’s place. Once they arrived in Rome, he let the bear go, and it lumbered back to its native forest.

This taming of the wild bear is an allegory for how Corbinian tamed the ferocious Bavarian pagans, but, in religious art, Corbinian is often depicted with a literally saddled bear beside him. As its patron saint, Corbinian’s saddled bear became the heraldic symbol for the town of Freising. And, given the legend, Corbinian became the patron saint of porters and carters, which is why you will find him depicted in the lüftlmalerei at Ludwigstraße 38 — an image which harkens back, not only to the Bishopric of Freising which ruled this area for five hundred years, but also to when this street was still the “Rottstraße,” and porters and merchants traveled along this road between Augsburg and Venice.

In the center of this particular lüftlmalerei, you can make out the distinctive shape of the Wetterstein Mountain range overlooking Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Ludwigstraße 39.

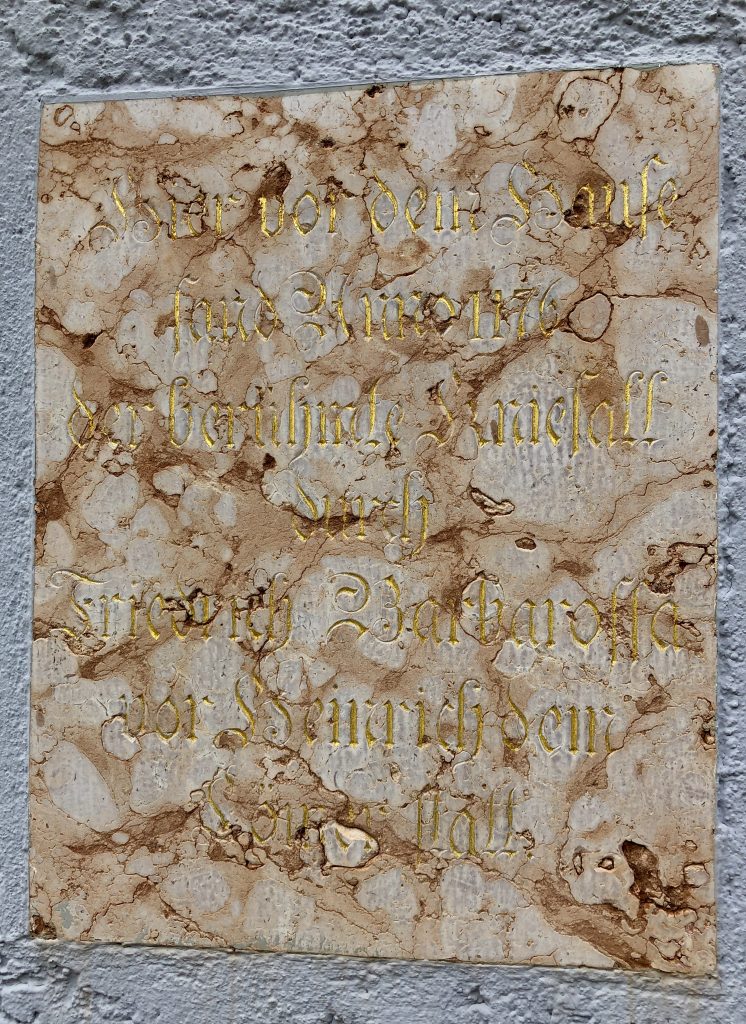

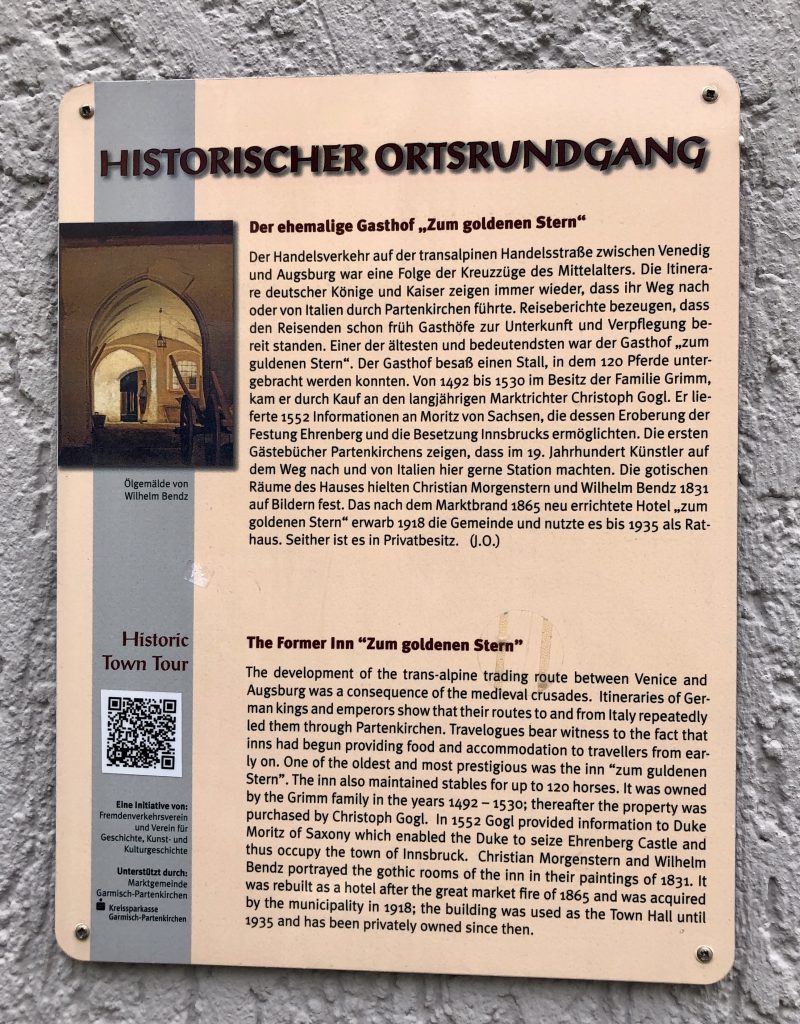

According to the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Tourist Office plaque on the wall outside, this building was an inn and stable as far back as the 15th Century.

After the 1865 fire, it was rebuilt as a hotel.

Before Partenkirchen was combined with nearby Garmisch this was the Partenkirchen town hall from 1918 until 1935.

The Winter Olympic Games in 1936 literally put the town of “Garmisch-Partenkirchen” on the map.

For thousands of years, the independent towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen stood separated by the Partnach river between them. As so happens when one is trapped together in such close quarters for so many centuries, a rivalry naturally formed between the two.

According to local historian Alois Schwarzmüller and his meticulously well researched website, while the two towns maintained their own post offices, tax offices, and town halls, given that they were just a hop across a small stream from each other, trade unions and companies and even the train station consolidated, hyphenating the name of their two towns together as “Garmisch-Partenkirchen.”

While there had been some consideration for the towns, themselves, to consolidate resources around the time of the First World War, since then, however, the municipal governments — the two separate eleven-member town councils and mayors — gave it no serious consideration.

Until 1931.

In 1931, the International Olympic Committee awarded Germany the 1936 Olympics. At that time, Germany was still the Weimar Republic, and both the Summer and Winter Games were held in the same country in the same year.

Berlin, the capital, was the obvious host for the Summer Games, but there were multiple venues vying for the Winter Games: the towns of Schierke in the Harz Mountains, Feldberg in the Black Forest, Oberhof in Thuringia, and Schreiberhau and Krummhübel (now the towns of Szklarska Poręba and Karpacz) in present-day Poland.

The Olympic Committee ultimately decided on the two separate but nearby towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen in the Bavarian Alps. The head of the organizing committee for the 1936 Olympic Games, Theodor Lewald (1860-1947), favored Garmisch and Partenkirchen from the outset.

While the Olympic Committee seemed to have no issue with the Winter Games taking place in two adjoining towns — according to the Olympic Committee’s 1933 Charter, “[all] events must all take place in the town selected, either at the Stadium or in its neighbourhood” — documents show the Führer did not want to receive the world in two separate host cities. For this reason, he personally ordered a merger by force of Garmisch with Partenkirchen.

“It wasn’t about Garmisch or Partenkirchen, Hitler didn’t care,” local historian Alois Schwarzmüller explained in one online article. “He wanted to demonstrate a new, unified Germany to the world. Inner unity, power, strength, and size.”

While the Winter Games were essentially a rehearsal for the Summer Games in August, as Christopher Hilton wrote in his book, Hitler’s Olympics (2006), “The world would travel to what had been, such a short time before, a defeated, broken country — humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles imposed by the victors, ravaged by hyper-inflation so intense that people paid for their meals course by course as the currency devalued while they were eating — and would suddenly find themselves in a land of full employment, confident citizens and faces ruddy with health.”

Individual town pride might have distracted from that message.

The Powers-That-Be decided that the towns would merge together as a single municipality by January 1, 1935.

In July of 1933, while both communities’ councils and mayors agreed with the merger, there was no concrete plan for how the merger would affect administration of the roads, power, sewage, or police. They outright disagreed on such details as where the new town hall would be and whether “Garmisch” or “Partenkirchen” ought to come first in the new hyphenated name. As the Partenkirchen town council noted in this document: “According to the provisions of the municipal code, there is no amalgamation of municipalities, only the dissolution of one municipality and its incorporation into the other. One community dies, while the other continues to exist on a larger scale.”

When the two municipal councils continued to resist merger by the deadline, Gauleiter Adolf Wagner summoned the Mayor of Garmisch, Josef Thomma, the Mayor of Partenkirchen, Jakob Scheck, and Garmisch town council member and Nazi Party member Engelbert Freudling to Munich on December 31, 1934.

That very evening, upon the their return, the Garmisch town council convened.

As notes of that special council meeting show, Engelbert Freudling reported on their morning in Munich, saying, in part:

"The negotiations were begun under the motto: the Führer Adolf Hitler wishes that all inhibitions and obstacles that still exist in Garmisch - Partenkirchen and that are necessary to be rid of for the implementation of the Olympic Games must be avoided without any debates. Paths must be cleared. [...] [O]r accept the possibility that the entire town council will be arrested and sent to Dachau. [...] Our objections have been recognized, but it would never be possible to stop the merger. [...] Then we were given the order to go home immediately, to call the local council as quickly as possible and to make the decision which takes into account the order of the state government. We have been told that we are not Nazis if we do not want to understand what the government wants. The decision we have to make has been prescribed for us in Munich and is now to be taken unanimously and brought to Munich as quickly as possible by 10 a.m. tomorrow. It is the order of the State Ministry and the wish of the Gauleitung that the local council comes together, otherwise we would have to take the already announced consequence."

As determined already, and under the threat of arrest and imprisonment, the independent councils of the towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen resigned. A new “Garmisch-Partenkirchen” town council was formed, and a new mayor was chosen, all eleven members and the mayor appointed by the Nazi Party — not a one of them elected by the citizens of this newly merged town.

In a speech to the first merged Garmisch-Partenkirchen council meeting, on January 4, 1935, District Administrator Wiesend said:

"What was a complete impossibility during the liberal-democratic system with its misunderstood self-administration has now become deed and reality: the merging of the two communities of Garmisch and Partenkirchen, which have been living and working independently for centuries, into a single political body under public law. In reality, Garmisch-Partenkirchen has long since become a unified term for every outsider from Germany's winter sports world, as a spa and tourist resort with international standing. It was precisely for this reason that the Führer determined that Garmisch-Partenkirchen should be the arena for the 1936 Winter Olympics. Here in Garmisch-Partenkirchen it should be shown abroad what National Socialist Germany is: the unity, power, strength and size of the new empire, its hospitality and love of peace, its organization, discipline and performance should be demonstrated to the world in a clear manner. Garmisch-Partenkirchen thus becomes the radiation of National Socialist will in general, it becomes the embodied program of National Socialist Germany. What National Socialism wants to show here is the unified German fatherland, and it is impossible to offer a picture of particularism and small states here before the eyes of the whole world.”

Sports facilities were built for the Winter Games, up to the Olympic requirements. The ice skating rink on the Garmisch side, the ski jump and opening and closing ceremony pavilion, the Olympia Stadion, on the Partenkirchen side.

The Olympia Stadion was decorated with sculptures representing the Olympics, but with a touch of Nazi flair — as Susan Sonntag described in her article, Fascinating Fascist, these nudes are symbolic Nazi art. I believe the sculptures were done by Wackerle.

The forced association also led to the construction of a new town hall.

That new building was done by Ostler in the new center of the town near the train station, covered in lüftlmalerei by Wackerle, in the Nazi style, and the new town square was named Adolf Hitler Platz.

Thus, this building on Ludwigstraße, the former Partenkirchen town hall, was vacated and sold.

Above the windows now, a series of gold lüftlmalerei medallions with no allusions to Nazis, but instead hinting at the broader history of Bavaria, ringed with laurel wreaths — reminiscent of the Olympic wreaths:

The Münchner Kindl, the coat of arms of the city of Munich;

Bavarian King Ludwig II, the Fairytale King;

Patrona Bavariae holding an infant Christ;

And the coat of arms of a combined Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Ludwigstraße 40, was built as a “Ballenhaus” in 1516 for the temporary storage of merchant goods. About 25 years later, a part of the house was separated from the rest to serve as a grain or “Schrannen” building. All the grain, coming in from elsewhere, was stored and sold on from here. For a short time, the building also housed a so-called “Brotbank” (“bread bank”): All the bakers had to take their bread here. A “Brothüter” (“guardian of the bread”) then sold it on. Later, a primary school moved in, followed by the local government of the town of Partenkirchen.

On the wall facing Ballengasse, a sundial honoring this building’s time as grain storage place, with a Bavarian man and women harvesting, and the motto: “Jung Arbeiten und sparen – Goldene Frucht in alten Jahren” — or “In youth, work and save for golden fruit in old age.”

This lüftlmalerei was originally painted by Heinrich Bickel some time before 1945.

At Ludwigstraße 41 the walls are decorated with elaborate sgraffiti and a lüftlmalerei of Patrona Bavariae, all done by Heinrich Bickel some time before 1945.

This building used to house a bakery and coffee-shop, and the images depicted in plaster — a woman with grain, a lady with a jug of rum, a sugar loaf, a beehive, and a chicken with an egg — are all ingredients of fine baking.

Saint Mary has long been worshipped in Bavaria.

Bavarian Duke Theodo — Duke Grimoald’s father — founded a church dedicated to the Nativity of Saint Mary in Freising around 715 AD. In 739, that church became the center of the newly created Bavarian diocese, and ultimately what is now the Freising Cathedral — where Saint Corbinian’s remains are entombed.

However, the veneration of Mary as the patron saint of Bavaria (in Latin: “Patrona Bavariae“) was first unofficially established by Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria (1573-1651).

A devout Catholic, in 1610 he had a coin minted with Mary depicted for the first time as the patron saint of the city of Munich.

In 1616, he had a bronze statue called the “Patrona Boiariae” displayed on the west side of the Munich Residenz, the royal palace of the Wittelsbach rulers of Bavaria.

In the statue, the Mother of God stands with her right foot on the crescent moon, with a scepter in her left hand and a high crown identify her as Queen of Heaven. In her right hand she holds the Christ child, in whose left hand he holds a globus cruciger — or a cross-topped orb — as a sign of his sovereignty over everything. The head of the Blessed Mother is ringed by twelve stars symboling the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

This image is fashioned after the vision in the Revelation of John of “a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.” (Rev 12:1).

During the Thirty Years’ War, Elector Maximilian I vowed to build a “godly work” if the cities of Munich and Landshut were spared.

Although the war would not end for another full decade, in 1638 he erected the Mariensäule, the “Column of Mary”.

The Latin inscription on the base of the pillar refers to his vow and to Mary for the first time as protector of Bavaria: “For the preservation of the homeland, the cities, the army, himself, his house and his hopes, Maximilian, Count of the Palatinate, gratefully and humbly erected this permanent monument to the most benevolent great god, the virgin goddess of birth, the gracious mistress and the most generous patron saint of Bavaria”.

The column is crowned by a gilded statue of Mary which resembles the statue at the Residenz with Mary standing on the crescent moon and wearing a crown, but opposite from the other statue as she’s and holding an infant Jesus in her left hand and a scepter in her right.

A year later, in 1639, four bronze putti were added to the base, which allegorically refer to Psalm 91 verse 13, written in abbreviated Latin on their shields: “Super aspidem et basiliscum ambulabis et leonem et draconem conculcabis“, or: “You will walk over the serpent and the basilisk and you will trample over the lion and the dragon.”

The hero putti are fighting four plagues of mankind: the lion embodies war, the basilisk embodies the plague, the dragon embodies famine, and the snake embodies a lack of faith.

In 1845, the square where this statute stands, once called “Market Square,” was accordingly renamed “Marianplatz,” or “Mary’s Plaza.”

The the column has always been considered the very center of the Bavaria. Even today, it is the zero point for the mile markers on all the roads that lead from Munich.

On April 26, 1916, during the First World War, at the request of Ludwig III, the last King of Bavaria, Pope Benedict XV officially declared Mary the patron saint of Bavaria.

At Ludwigstraße in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, today, you can see how Heinrich Bickel paid homage to the Mariensäule with his lüftlmalerei, painting the “Patrona Bavaria” as she is depicted in the sculpture at the top of the column on Marianplatz, with three-dimensional plaster putti pulling aside curtains to reveal her on the wall of Ludwigstraße 41.

Ludwigstraße 45.

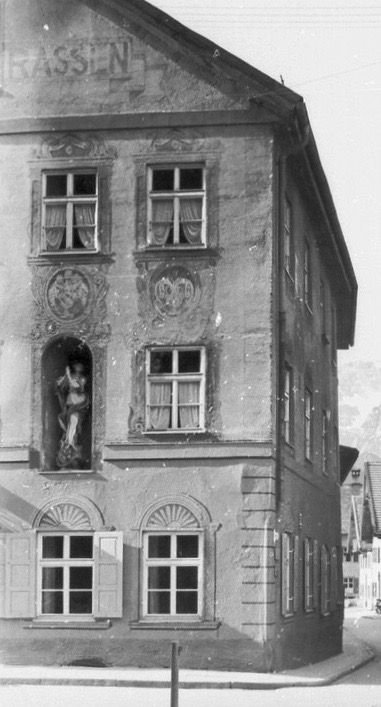

The restaurant at the Rassen Gasthof is known for its traditional German cuisine and is open every day from 7:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. with full cuisine. Enjoy a selection of Bavarian delicacies and delicious locally brewed beer.

The largest peasant theater in Bavaria is located in the Rassen, an ideal venue for all your business or family occasions. You also benefit from a massage service and relax on the terrace in the summer months.

The history of Gasthof Zum Rassen dates back to the 16th century.

Gasthof zum Rassen is named for Saint Rasso of Andechs (ca. 900-953), a Bavarian count and military leader, pilgrim, and saint. He led the Bavarians against invading Maegyars (modern day Hungarians) in the tenth century. No contemporary Vita of Rasso has survived and various legends arose around his cult in the late Middle Ages.

Some 12,000 miracles are attributed to the Saint between 1444 and 1728.

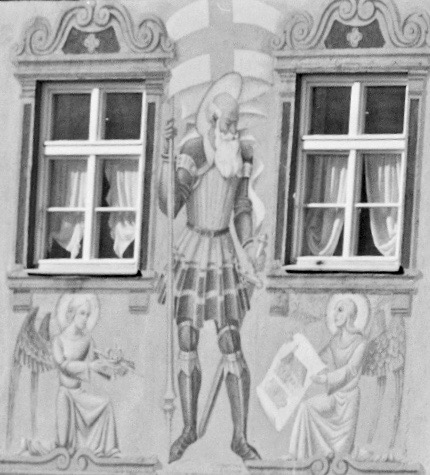

In the center of the front of the building, a lüftlmalerei of Saint Rasso by Gerhard Ester, painted in 1988.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archives, you can see a photograph by August Beckert taken in 1950 of the lüftlmlaerei (painted some time before 1935) on the front of this building before Gerhard Ester’s renovation, here, and before there were any lüftlmalerei of any kind back in 1927, here.

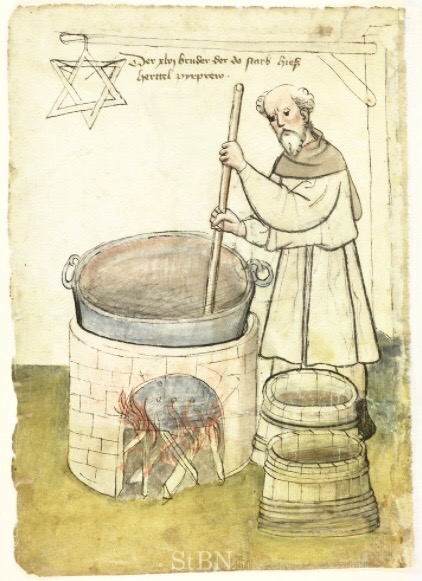

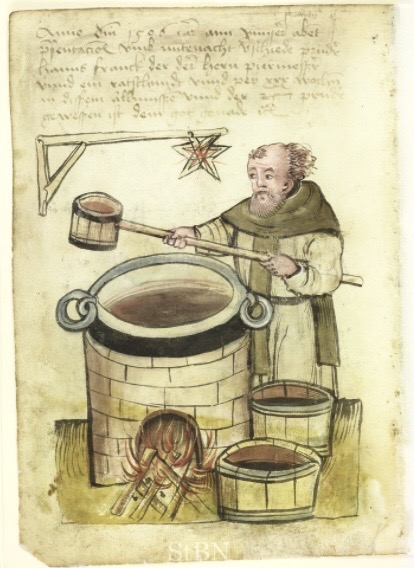

The six-pointed star hanging from the bottom of the coat of arms should not to be confused with the Star of David, the symbol of the Israelites and Judaism.

The star painted here, called a Brauerstern, developed independently in the region around Nuremberg solely in connection with the brewing and serving of beer.

The Brauerstern, or the “Brewer’s Star,” (also known as the Bierstern, Bierzeiger, Braustern, Bierzoigl, or Zoiglstern) is a six-pointed star consisting of two intertwined triangles — one pointing up, the other pointing down — and has been used as a symbol for beer brewing in Bavaria since at least the 14th century.

The oldest known recorded image of the star in relation to brewing dates backs to around 1425, in an illustration in the Nuremberg House Books, or the Twelve Brothers’ Books, a collection of portraits of residents of two Nuremberg poor houses, the so-called “Twelve Brothers’ Houses.”

In the books, there are images of a men dressed as monks standing in front of a brew cauldron. Above them, the Brauerstern can be seen hanging from a pole. In one drawing from 1506, the man is depicted using a Bierschöpfer, a measuring ladle (literally a “beer creator”), to determine beer amounts for tax purposes.

In Nuremberg in the Middle Ages, unlike most of the rest of Germany, there were no brewer guilds in the city. Rather, the city sold the right to brew beer for a tax. Thus, back in the day — with no guild symbol or coat of arms to display — those who were allowed to brew and sell beer would hang the Brauerstern outside their establishment. For a largely illiterate population, this was the same as bars today putting out a neon sign flashing the word “BEER”.

Ludwigstraße 46.

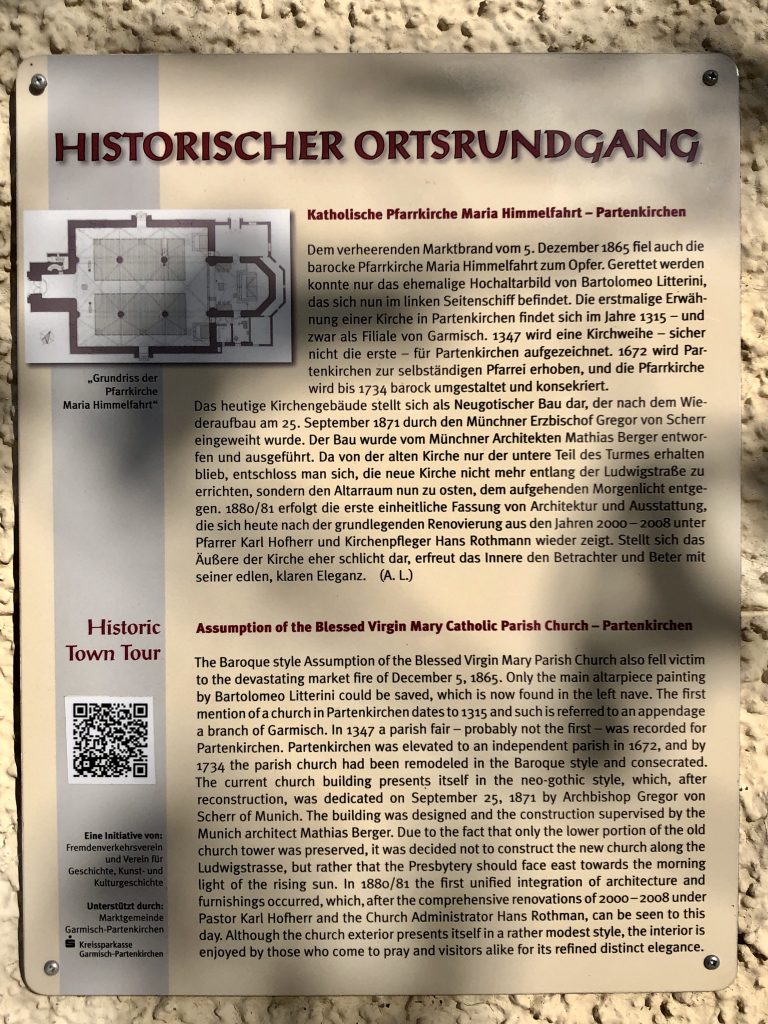

“The Baroque style Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Parish Church also fell victim to the devastating market fire of December 5, 1865. Only the main altarpiece painting of Bartolomeo Litterini could be saved, which is now found in the left nave. The first mention of a church in Partenkirchen dates to 1315 and such is referred to an appendage a branch of Garmisch. In 1347, a parish fair — probably not the first — was recorded for Partenkirchen. Partenkirchen was elevated to an independent parish in 1672, and by 1734, the parish church had been remodeled in the Baroque style and consecrated. The current church building presents itself in the neo-gothic style, which, after reconstruction, was dedicated on September 25, 1871 by Archbishop Gregor von Scherr of Munich. The building was designed and the construction supervised by the Munich architect Mathias Berger. Due to the fact that only the lower portion of the old church tower was preserved, it was decided not to construct the new church along the Ludwigstrasse, but rather that the Presbytery should face east towards the morning light of the rising sun. In 1880/81, the first unified integration of architecture and furnishings occurred, which, after the comprehensive renovations of 2000-2008 under Pastor Karl Hofherr and the Church Administrator Hans Rothman, can be seen to this day. Although the church exterior presents itself in a rather modest style, the interior is enjoyed by those who come to pray and visitors alike for its refined distinct elegance.”

On December 5th, 1865, almost all buildings in Ludwigstrasse burned down, including the old parish church. Only a few years later, the people of Partenkirchen celebrated the consecration of their new, neo-Gothic style parish church, an enormous accomplishment. The original, destroyed church was a baroque church, of which sadly no pictures remain. Luckily, the showpiece of the church was saved: a painting by Litterini dating back to 1731, which depicts the Ascension of Mary. It is said to be the only picture of the Venice painter north of the Alps. It is now located at the left side of the church. The painting was originally donated by a Würzburg merchant. He worked for a company in Venice and was married to a lady from Partenkirchen. As this lady was very beautiful, she is said to have been the model sitting as Maria.

Three years after the fire, the foundation stone for a new church was laid on June 13, 1868 according to plans by Matthias Berger . While the baroque church was oriented to the southeast, the neo-Gothic new building with choir towards the northeast was built. Ferdinand Barth created templates for the coloring . The church was consecrated on September 25, 1871 by Archbishop Gregor von Scherr .

It is not known when the original church was built in Partenkirchen. In any case, “Partenchirchen”, as it is said in a document from around 1150, would have been a church town during the bajuwarization and the associated Christianization in the 8/9 century. The first documented church is the Benefit Church of the Holy Spirit from the year 1315. The Partenkirchner citizen Konrad Weiß made it possible for permanent parish services to be performed by setting up a beneficiary position, which was borne by interest from donated land. Even the tithe then common was equally entitled to sovereignty and parish.

The church was expanded in Gothic style in 1347 and consecrated in honor of the Mother of God. Weiss’s benefit was raised to the independent parish of the Assumption in 1672. Even though Partenkirchen was more important than Garmisch as a market town for centuries, the Partenkirchen parish was still a branch church of Garmisch until then, which had its first church before 800.

During the term of the pastor Dr. Matthias Samwever enlarged the church around 1730 and – according to the taste of the time – the transition from Gothic to Baroque style. The renovation work is attributed to the Wessobrunn master builder Schmuzer, who at the same time built the new parish church in Garmisch and expanded the St. Anton pilgrimage church.

In December 1865 the “Great Fire” in Partenkirchen destroyed 76 houses and the parish church. The high altarpiece by Litterini and some other treasures such as monstrances, goblets, guild sticks, paraments were saved.

With the old church, from the inside of which there is no exact description or photos or representations, the old Partenkirchen also went under, with its upper floors on top of the masonry earthen, occasionally also made of brick, attached block buildings made of wood or widely protruding roof trusses with fretwork, Shingle roof and sweeping gutters, called ‘Urscht’. The former high altar painting “Ascension” by Litterini (sign. 1731), a student of Titian, hangs today on the left wall, above the side entrance. The central figure of Mary in the new high altar comes from the local sculptor Max Kaiser. A church window (designed by H. Bickel) shows the market fire of 1865.

In June 1868 the reconstruction of the church began under the Munich architect Matthias Berger in the neo-Gothic style.

The church was painted in 1908 by the painter Hans Schmid with flower tendrils on the walls and pillars and a deep blue starry sky. 1945 – 1948 they wanted it to be purist again and painted over everything.

Ludwigstraße 47.

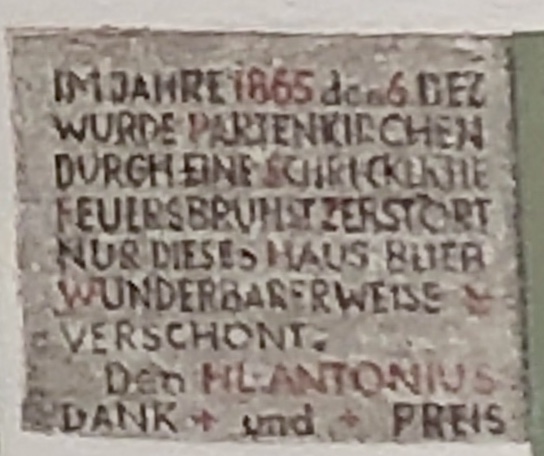

This building has been home to the Werdenfels Museum since 1973. The building dates back to the 15th century and is the only survivor of the 1865 “great market fire” in the central market area. A legend says that on the day of the fire a gypsy woman had asked residents of Ludwigstrasse, to let her warm up some milk for a small child. The residents of house no. 47 are said to have been the only ones who helped the woman. Maybe it was this good deed that protected the house from the flames. A mural on the gable of the house shows the building at that time. The interior of the house has also maintained its original state. It provides the ideal surroundings for the Werdenfels Museum.

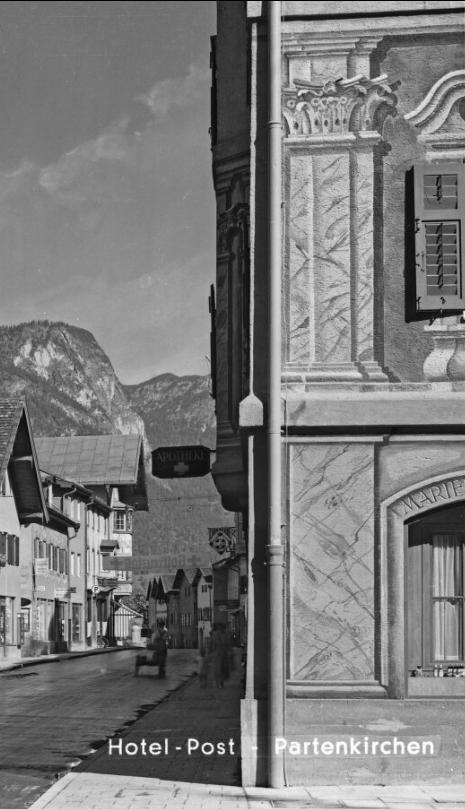

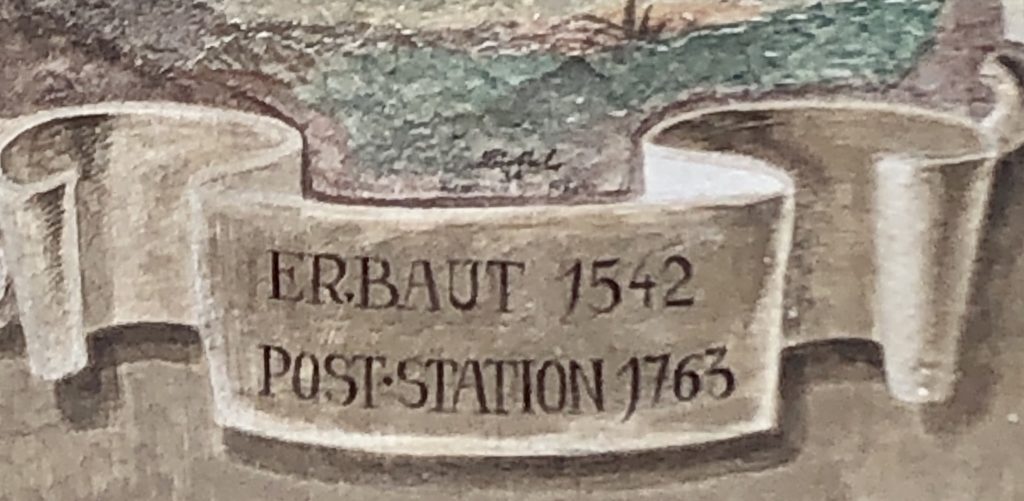

Ludwigstraße 49, Post Hotel O. Stahl.

In 1763 the Prince of Thorn and Taxis installed a post station here. Later it became the Royal Bavarian Post Office (“Königlich-Bayerische Posthalterei”) endowed with all rights and duties. All letters, packages and money were handled here.

“Built in 1542, Post Station since 1763.” Lüftlmalerei of Postillones in historical costume from the years 1600, 1700, and 1800, painted by Heinrich Bickel in 1934 and restored by Gerhard Ester in 1977.

“Painted by Heinrich Bickel at the Postillon inn in Garmisch, approved, attached here and supplemented by G. Ester,” in 1981.

Photos of this building in 1910, before the lüftlmalerei were painted on its walls, can be found online at the Bavarian State Archives, here.

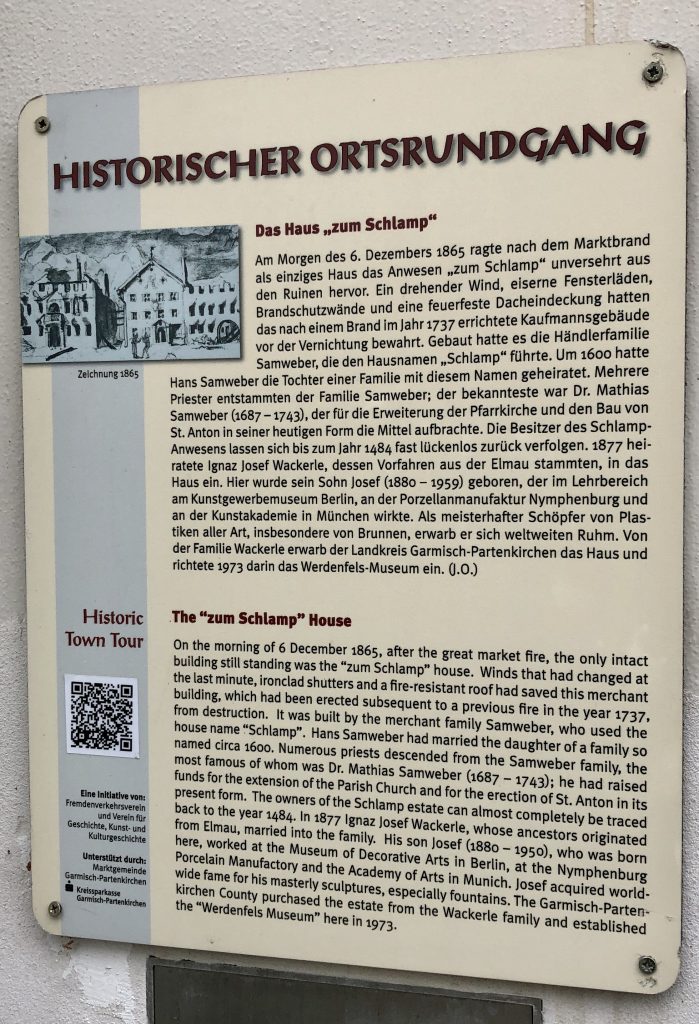

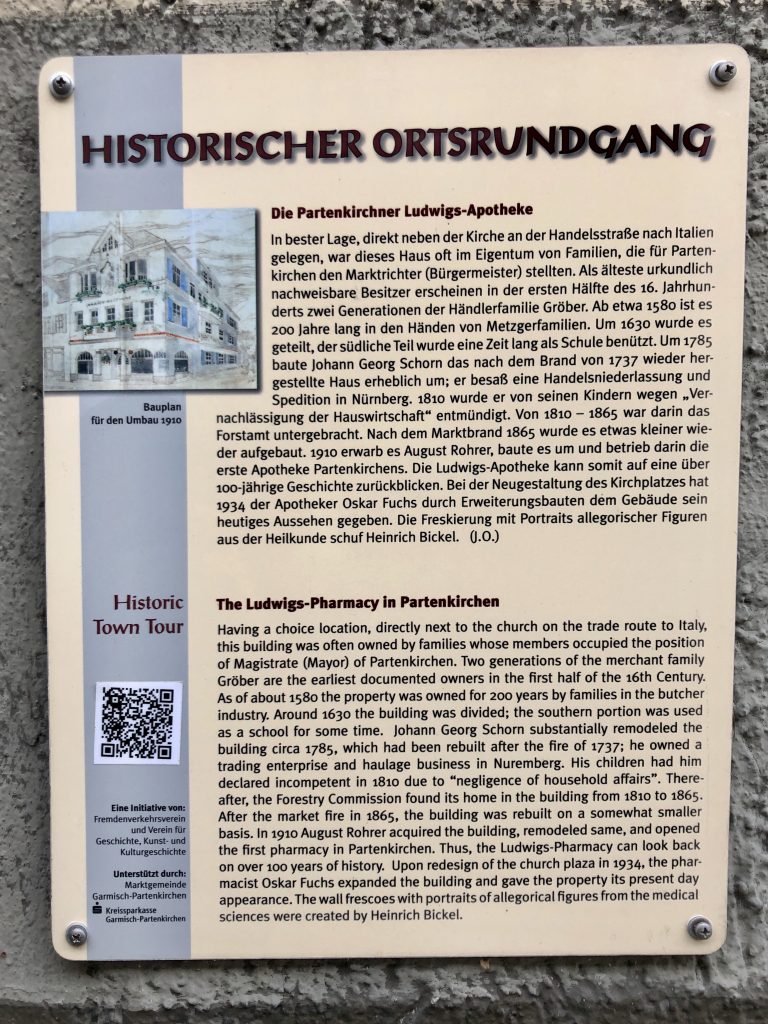

The Ludwigs-Apotheke at Ludwigstraße 50 is covered in Lüftlmalerei originally painted by Heinrich Bickel some time before 1934,1 redone in 1954,2 then redone again by another artist some time after 1973.

Pharmacist August Rohrer first founded a pharmacy here and named it for the church beside it, the “Marien-Apotheke,” in 1910. In 1953, the pharmacy was renamed the “Apotheke am Kirchplatz,” or the “Pharmacy on the Church Square.” In 1968 it was renamed “Ludwigs-Apotheke” after King Ludwig II, who is also the namesake for the street.

As can be seen in this photograph from the Bavarian State Archives, the faux columns were already painted on the corners of this building in 1935.

You can also see at the Bavarian State Archives, this photograph of this building as it looked in 1973. Notice that the busts above the windows have since changed, and the curious character wearing a coxcomb did not yet exist.

At the top of the window frames, images of sculpted busts of famous names in medicine:

Asclepius, or “Äskulap” in German, was the Roman god of medicine and healing, whose rod, a snake-entwined staff, remains a symbol for medicine today.

Hygieia, his daughter, was a goddess of health and cleanliness. Her name is the source for the English word “hygiene.”

Hippocrates (circa 460 – circa 370 BC) considered the “Father of Medicine,” was a Greek physician credited with making medicine a profession, founding a medical school, and coining the Hippocratic Oath, which is still in use today.

Cosmas and Damian (born sometime around 303 AD) were twin brothers who practiced medicine without a fee in what is now Syria and who died as Christian martyrs. They are the patron saints of medicine, and, in art, as here, they are often depicted dressed as medieval doctors in red cloaks with round hats.

Dr. Walter Imhoff was the present owner’s grandfather, a pharmacist who, himself, ran another pharmacy, Der Alten Apotheke on Marienplatz, from 1959 to 1979,3 and bought this building in 1962.4

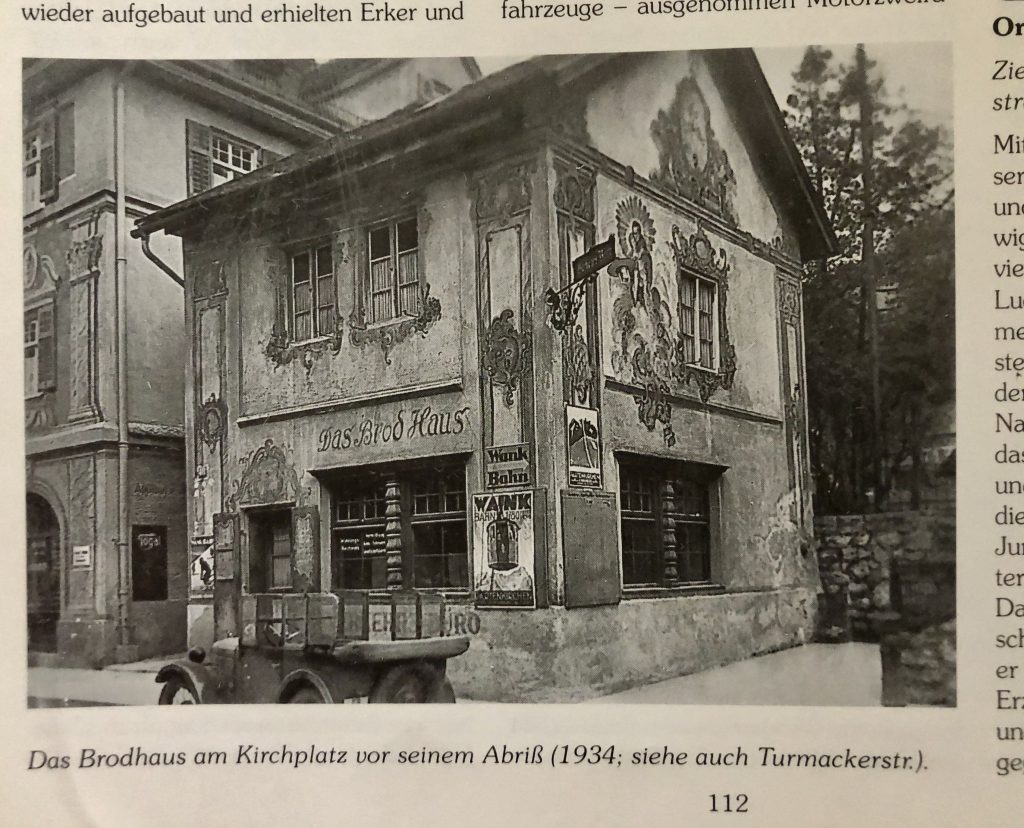

In their book Die Strassenamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen, the authors included a photograph of “Das Brod Haus” — a tiny building covered in lüftlmalerei — as it looked in 1934.

Starting in 1562 with the Brodhausordnung — the “bread house regulations” — all the bread baked by bakers was sold in this one common shop. After the market fire in 1865, the Brodhaus was rebuilt, but seven years later. The Brodhaus remained a bread shop until 1868, then it became a general store. And, for a time, it housed the Partenkirchen Tourist Office.

Between 1922 and 1925, Heinrich Bickel painted it with frescoes.

The building used to sit just beside the pharmacy at Ludwigstraße 50. It has since been demolished and its lüftlmalerei forever lost.

Ludwigstraße 52, the original Krätz bakery.

Their second branch, with lüftlmalerei by August Maninger on its walls, is located on Schloßwaldstraße in Burgrain.

Ferdinand Krätz founded the Krätz bakery on Ludwigstraße in 1772.

After the fire in 1811, the bakery moved from lower Ludwigstraße to its current location. After the fire in 1865, the bakery was again rebuilt.

Above the door, in grisaille, Bavarian harvesters, and above them, lions with swords and pretzel as a coat of arms with a motto, all painted by Heinrich Bickel some time after 1945.

The pretzel has been the symbol for German bakers since at least 1111 AD.

Their name, “Bretzel” in German, derives from the Latin word “brachiatellium” — translated as “little arms” — because the pretzel symbolizes arms folded to pray. This was the bread Christ supposedly offered to his followers at the Last Supper. The twists create three holes which came to represent the Christian Trinity –- the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Thus, the pretzel took on religious connotations for good luck and prosperity.

Legend has it, that in 1323, Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria — namesake of the street — awarded bakers an official coat of arms for their participation in the Battle of Mühldorf. At the center of their banner, the image of a pretzel.

In 1348, the pretzel of their crest was overlaid with the Bohemian royal crown above it.

For their services during the first Turkish siege of Vienna, in 1529, two lions on either side were added.

As the story goes, during the siege, the Ottoman Turks dug a tunnel under the city wall at night. The pretzel bakers — who were awake and busy baking when the wall was breeched — are said to have heard the sound of digging first, and, when the Turks broke through, they fought “like lions.” For saving the city, they were awarded the two lions on their guild’s coat of arms.

In 1690, in recognition of their services during the second Turkish siege, Emperor Leopold gave the bakers’ guild permission to arm the lions with swords.

Hence the coat of arms you see on the bakeries on Ludwigstraße today, and the motto painted under the lüftlmalerei here: “The golden sword, two lions wild, are the baker’s shield of honor”.

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, p. 124: "A 55 Ludwigstraße 50, Ludwigs-Apotheke: Medaillons, Spruch; vor 1945".

- "Deshalb wurde die Apotheke 1954 in Ludwigs-Apotheke umbenannt und die Fassade von Heinrich Bickel mit der typisch oberbayerischen Lüftlmalerei verziert." https://www.ludwigs-apotheke-partenkirchen.de/#1 (last accessed November 21, 2022).

- "Sein Nachfolger wurde Walter Imhoff, bis dahin Besitzer der Pfauen-Apotheke München, der die Apotheke am 1. Oktober 1959 zunächst in Pacht übernahm." https://www.alte-apotheke-garmisch.de/geschichte/ (last accessed November 21, 2022).

- Wanninger, Alexandra. "Generationswechsel in der Ludwigs Apotheke," Kreisbote Garmisch, Dec 26, 2020: "Alle paar Meter wird sie erkannt, lächelt, grüßt zurück, gibt einen kleinen Gesundheitstipp. Das historische Anwesen mit der Heinrich-Bickel-Fassade ist schon seit 1962 in Familienhand. Damals kaufte das Apothekerpaar Walter und Lore Imhoff das Haus mit der ältesten Apotheke Partenkirchens, die 1910 gegründet wurde." https://www.ludwigs-apotheke-partenkirchen.de/aktuelles/news/generationswechsel-in-der-ludwigs-apotheke/ (last accessed November 21, 2022).