- "Historie". Wittmann Shuhe und Orthopädieschuhtechnik. http://www.schuh-wittmann.de/historie.html. Accessed 25 November 2020: "1920 Eröffnung des Schuhgeschäfts durch Sebastian Wittmann sen. und Josefa Wittmann in der Ludwigstraße in Partenkirchen".

- "Historie". Über Uns. https://www.baeckerei-siess.de/ueber-uns/. Accessed 25 November 2020: "Die Bäckerei Sieß wurde am 1.12.1886 durch Bäckermeister Anton Sieß gegründet. Nachdem drei Söhne das Bäckerhandwerk erlernt hatten und sich später, jeder für sich, in Partenkirchen selbständig machten, wurde unsere Bäckerei im Jahre 1919 am heutigen Standort eröffnet. Als zweites Standbein wurde damals eine Landwirtschaft und ein Fuhrunternehmen (mit „Lohnkutscherei“) betrieben. Im Jahr 2005 übernahm der heutige Besitzer Christian Sieß von seinem Vater Benedikt Sieß, der die Bäckerei mehrere Jahrzehnte erfolgreich geführt hatte, den Betrieb. Bäckermeister Christian Sieß führt die Bäckerei nun in fünfter Generation im Sinne der Familientradition fort."

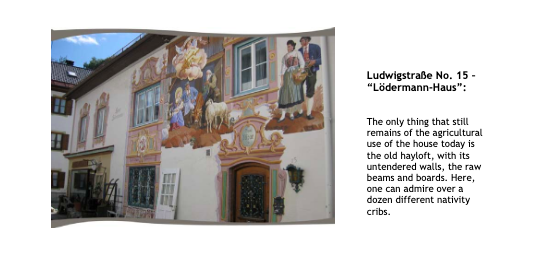

- Hornsteiner, Josef. "Verschwundenes Kunstwerk: Lüftlmalerei fällt Sanierung zum Opfer". Merkur.de. https://www.merkur.de/lokales/garmisch-partenkirchen/garmisch-partenkirchen-ort28711/verschwundenes-kunstwerk-lueftlmalerei-in-historischer-ludwigstrasse-faellt-sanierung-zum-opfer-11446714.html. Accessed 25 November 2020: "Das Gebäude mit der Nummer 15 an der Historischen Ludwigstraße zierte bis vor Kurzem noch ein filigranes Werk des Mittenwalder Künstlers Sebastian Pfeffer. Das Bild, das 1981 entstand, stellte eine Krippenszene mit der Geburt Jesu in alpenländischem Stil dar. Jetzt ist es weg. Hat bei einer Sanierung einer neuen Fassade Platz machen müssen. Das hat viele erschreckt, Einheimische, wie auch Urlauber, die dem Tagblatt geschrieben haben. [...] Der „Moar-Martl“, wie ihn die Einheimischen kannten, war als Krippenbaumeister über die Landkreisgrenzen hinaus bekannt. [...] Hausbesitzer Martin Simon beruhigt ihn. Die aktuell nackte Fassade bleibt nicht so. Im Gegenteil: „Es wird wieder eine Lüftlmalerei darauf entstehen.“ Und zwar von Sebastian Pfeffers Sohn Stephan. „Die ersten Gespräche haben bereits stattgefunden“, sagt Simon. [...] Keine Überraschung für Simon, blickt er auf die Geschichte des alten Gebäudes zurück: „Das Haus hat insgesamt schon drei verschiedene Malereien auf der Fassade gehabt“, hat er nachgeforscht. „Alle 20 Jahre ist ein neues Bild darauf entstanden.“ Das Haus Nummer 15, das so nach dem großen Marktbrand von 1865 zum ersten Mal gemauert wieder aufgebaut wurde, gehört zu einem sogenannten Denkmalensemble in der Historischen Ludwigstraße."

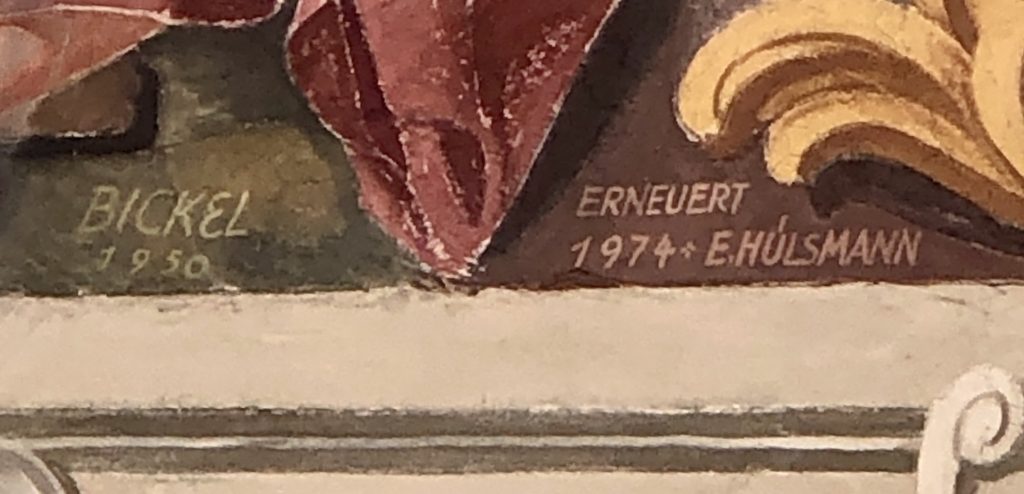

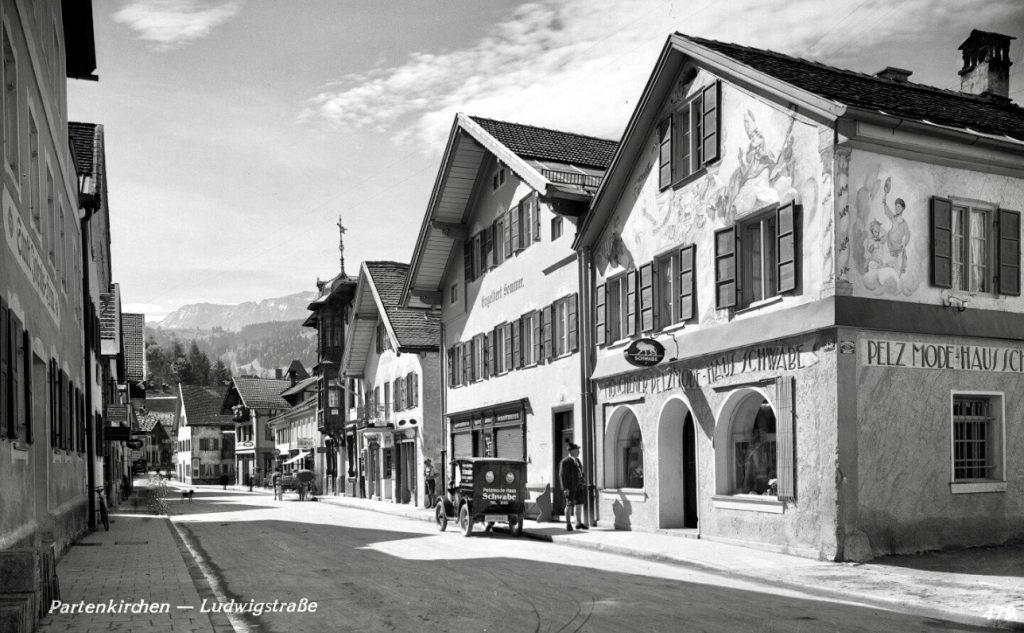

- Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege. Denkmalliste, Markt Garmisch-Partenkirchen. 11 November 2020, http://geodaten.bayern.de/denkmal_static_data/externe_denkmalliste/pdf/denkmalliste_merge_180117.pdf, p. 16: "D-1-80-117-148 Ludwigstraße 24. Fassade, mit reichen Malereien, von Heinrich Bickel, 1928."

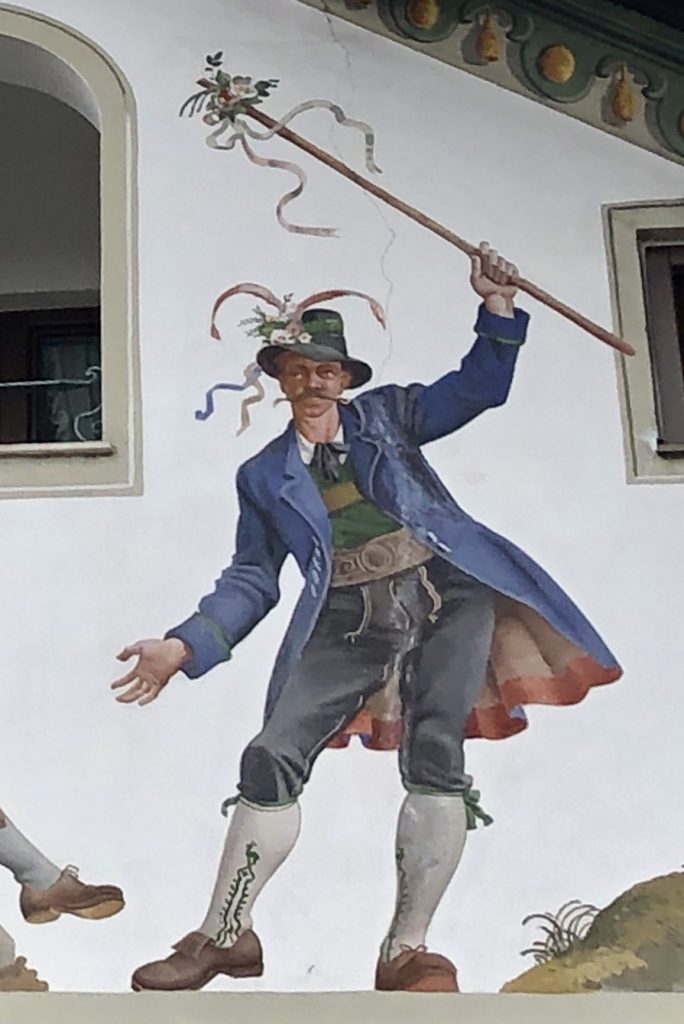

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, p. 125: "A 144 Ludwigstraße 24, Gasthof Fraundorfer: Zechende und tanzende Bauern, Hochzeitslader, Hund, in Scheinnische: Madonna, Kartusche mit Wappen; nach 1945."

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, p. 124: "A 65 Ludwigstraße 31, Haus Sommer: In Landschaft ruhendes Bauernpaar mit Partenkirchner Wappen, sowie Wappen mit Bär; Scheinarchitektonische Fassadenmalerei; erneuert von Hülsmann 1974; ursprünglich 1950".

Lüftlmalerei

A street by street guide to the fresco and facade paintings in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district