- https://www.schlosserei-klarwein.de/. Accessed 20 Nov 2020: "Gegründet wurde der Betrieb von Karl Entleutner im Jahre 1927."

- Bierl, Hermann. "Garmisch-Partenkirchen und seine Lüftlmalereien." Mohr, Löwe, Raute. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Landkreises Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Band 18, Verein für Geschichte, Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte im Landkreis Garmisch-Partenkirchen, 2020, p. 89: "214 Fürstenstraße 19 Schlosserei Karl Entleutner 1927 1939".

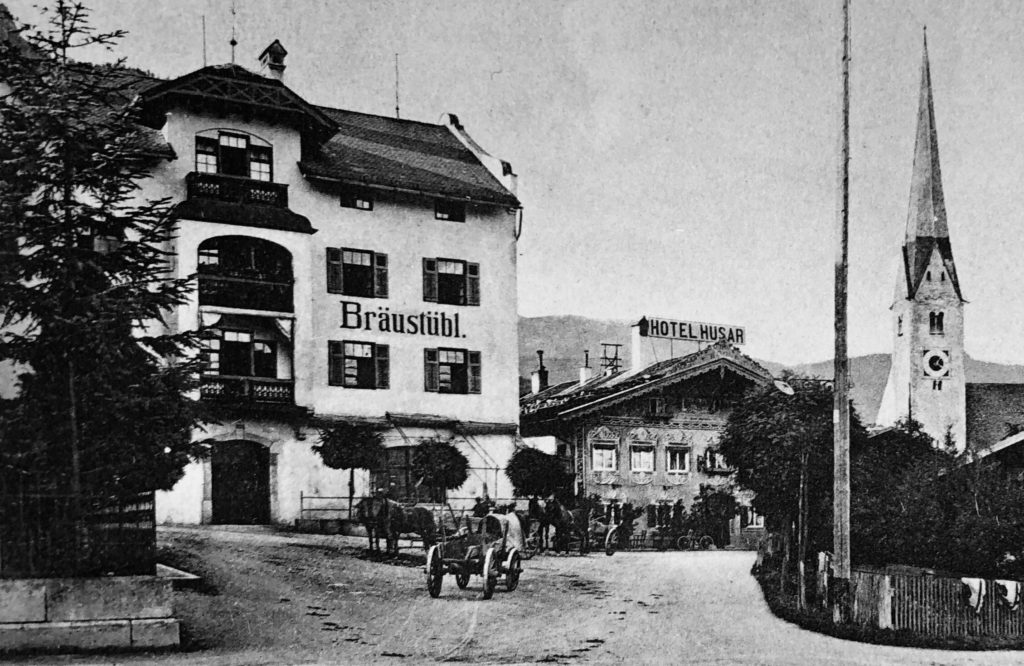

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, p. 122: "A 19 Fürstenstraße 23, Bräustüberl: Wandfries: zechende Werdenfelser Bauern und Bäuerinnen; 1933/39."

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, p. 44: "Ein weiteres Wandbild im Gastraum des Bräustüberls schildert die Gründung des Brauhauses im Jahre 1663. Bickel läßt in dieser vielfigurigen Komposition seiner Neigung zu breiter, erzählfreudiger Darstellungsweise und seiber Vorliebe für die Schilderung phantasievoller, historischer Kostüme freien Lauf: Er erzählt uns, wie der Freisinger Fürstbischof Albert Siegesmund vom Pfleger Martin Rosenbusch und Bräuverwalter Mielmuther den ersten Humpen Bier aus der von ihm gegründeten Brauerei kredenzt bekommt."

- https://www.braeustueberl-garmisch.de/index.php/wirtsleute. Accessed 20 Nov 2020: "Nachdem Sylvester Wackerle das Bräustüberl Anfang 2011 aus Altersgründen aufgab, ergriffen Robert Gebhart und seine Frau Martina diese Chance, sich einen Traum zu erfüllen. Die Leidenschaft zur Gastronomie im bayerischen Stil mit der Führung eines solchen Traditionslokal zu verbinden, bedeutet beiden schon etwas Besonderes."

- Adam, Peter, and Anton Jocher. Die Strassennamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Adam Verlag, 2001, p. 87: "[...] Hotel “Husar” in der Nähe der Alten Kirche, das 1611 in der heutigen Form ausgebaut und die, seit 1678 bestehende Schänke, 1735 erweitert wurde."

- Adam, Peter, and Anton Jocher. Die Strassennamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Adam Verlag, 2001, p. 87: "Berühmte Gäste wohnten hier, fast alle Mitglieder des Wittelsbacher Herrscherhauses: König Ludwig I und König Max II, König Albert und Königin Carola von Sachsen, zahlreiche Fürsten wie Fürst von Bülow und Großindustrielle wie Krupp, bekannte Künstler und Literaten wie Noe, Steub, v. Kobell, Karl Stieler, die Maler Adolf Menzel, Hubert v. Herkomer, der Großadmiral Alfred von Tirpitz und viele andere."

http://www.restauranthusar.de/historisches.html. Die Historie vom Husar. Accessed 21 Nov 2020: "Wie in den Gästebüchern nachzulesen ist, erholten sich hier bayrische Könige, wie König Ludwig I. und König Max II. ebenso wie auch fast alle Mitglieder des Wittelbacher Hauses. König August von Sachsen, König Friedrich Wilhelm von Württemberg, und in der Folge Wissenschaftler, Dichter, Schauspieler und Künstler von Kobell bis Heinz Rühmann geben Zeugnis von der belebten Geschichte des Hauses."

- The first mention of this particular lüftlmalerei I have found in print so far.

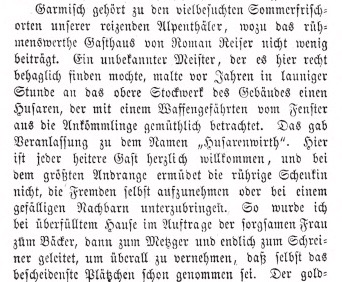

- Ingerle, Johann Nepomuk. Bayerns Hochland zwischen Lech und Isar. Fleischmann's Buchhandlung, München, 1863: "Ein unbekannter Meister, der es hier recht behaglich finden mochte, malte vor Jahren in launiger Stunde an das obere Stockwerk des Gebäudes einen Husaren, der mit einem Waffengefährten vom Fenster aus die Ankömmlinge gemüthlich betrachtet. Das gab Beranlassung zu dem Namen „Husarenwirth”. "

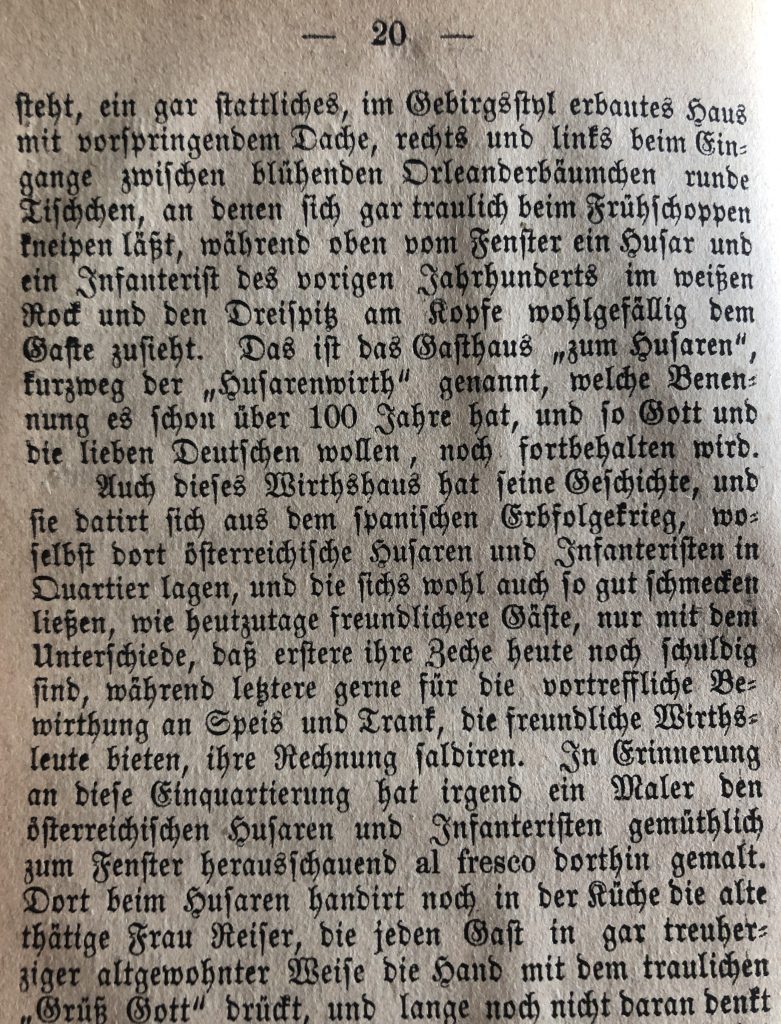

- Steindel, Ph. Garmisch und dessen gesammte Umgebung; Ein treuer führer mit Berücksichtigung aller Interessen der Touristen. Adam Verlag, 1882, p. 20: "Auch dieses Wirthshaus hat seine Geschichte, und sie datirt sich aus dem spanischen Erbfolgekrieg, woselbst dort österreichische Husaren und Infanteristen in Quartier lagen, und die sichs wohl auch so gut schmecken ließen, wie heutzutage freundlichere Gäste, nur mit dem Unterschiede, daß erstere ihre Zeche heute noch schuldig sind, während leßtere gerne für die vortreffliche Bewirthung an Speis und Trank, die freundliche Wirthsleute bieten, ihre Rechnung saldiren."

- Steindel, Ph. Garmisch und dessen gesammte Umgebung; Ein treuer führer mit Berücksichtigung aller Interessen der Touristen. Adam Verlag, 1882, p. 20: "In Erinnerung an diese Einquartierung hat irgend ein Maler den österreichischen Husaren und Infanteristen gemütlich zum Fenster herausschauend al fresco dorthin gemalt."

- Steindel, Ph. Garmisch und dessen gesammte Umgebung; Ein treuer führer mit Berücksichtigung aller Interessen der Touristen. Adam Verlag, 1882, p. 20: "Das ist das Gasthaus „zum Husaren”, kurzweg der “Husarenwirth” genannt, welche Benennung es schon über 100 Jahre hat, und so Gott und die lieben Deutschen wollen, noch fortbehalten wird."

- Rattelmüller, Paul Ernst. Lüftlmalerei in Oberbayern. Werbeabteilung Süddeutscher Verlag, 1960, p. 85: "Das Bild soll nach Aussage des Hausbesitzers an 200 Jahre alt sein. Nr. … (beim Husarnwirt) ist ein all- und altbekanntes Haus. Seinen Namen verdankt es einem gemalten Husaren, der aus einem blinden Fenster des I. Stockes herabsieht. Dieses Scherzgemälde wurde in Erinnerung an die Einquartierung österreichischer Husaren im unheilvollen Spanischen Erbfolgekrieg hergestellt. Die kriegerischen Gäste ließen sich’s damals gar wohl ergehen. Bei ihrem Abzug hatte der Wirt aber das Nachsehen, so ungefähr wie heute der gemalte Husar. — Die architektonischen Verzierungen des Hauses sind im Empirestil gehalten. Die Bemalung dürfte kaum älter als 120 Jahre sein."

- Adam, Peter, and Anton Jocher. Die Strassennamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Adam Verlag, 2001, p. 87: "Das Hotel wurde 1972 geschlossen. 1980 kaufte es die Marktgemeinde Garmisch-Partenkirchen, und 6 Jahre später wurde es renoviert und als Restaurant, ein Ziel für Feinschmecker in traditioneller bayrischer Umgebung."

- http://www.restauranthusar.de/historisches.html. Die Historie vom Husar. Accessed 22 Nov 2020: "Im Jahr 1801 wurde die Fassade im Empirestil bemalt, wobei der Lüftlmaler Zwink einen Husaren und Infanteristen an einem blinden Fenster hinzufügte, das dem Haus seinen heutigen Namen verlieh."

- Adam, Peter, and Anton Jocher. Die Strassennamen von Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Adam Verlag, 2001, p. 87: "Das Fresko wird oft dem Oberammergauer Lüftlmaler Zwink zugeschrieben, fehlt aber in seinem Werkverzeichnis."

- http://www.restauranthusar.de/historisches.html. Die Historie vom Husar. Accessed 22 Nov 2020: "Nach dem Augsburger Kalender von 1800 quartierten sich während der Napoleonischen Kriege auf dem Weg nach Tirol eine Abteilung französischer Husaren und ein Kommando verbündeter bayrischer Infanteristen hier ein, da das Weiterkommen an der Festung in Scharnitz scheiterte."

- http://www.restauranthusar.de/historisches.html. Die Historie vom Husar. Accessed 22 Nov 2020: "Der Aufenthalt der Soldaten wurde dem damaligen Wirt zu einer so grossen Last, dass er sich entschloss, sie über den heute „Franzosensteig“ benannten Weg durch das Wettersteingebirge ins Leutaschtal und somit in den Rücken von Scharnitz zu führen, so dass dieses zu Fall kam und Garmisch von der lästigen Einquartierung befreit wurde."

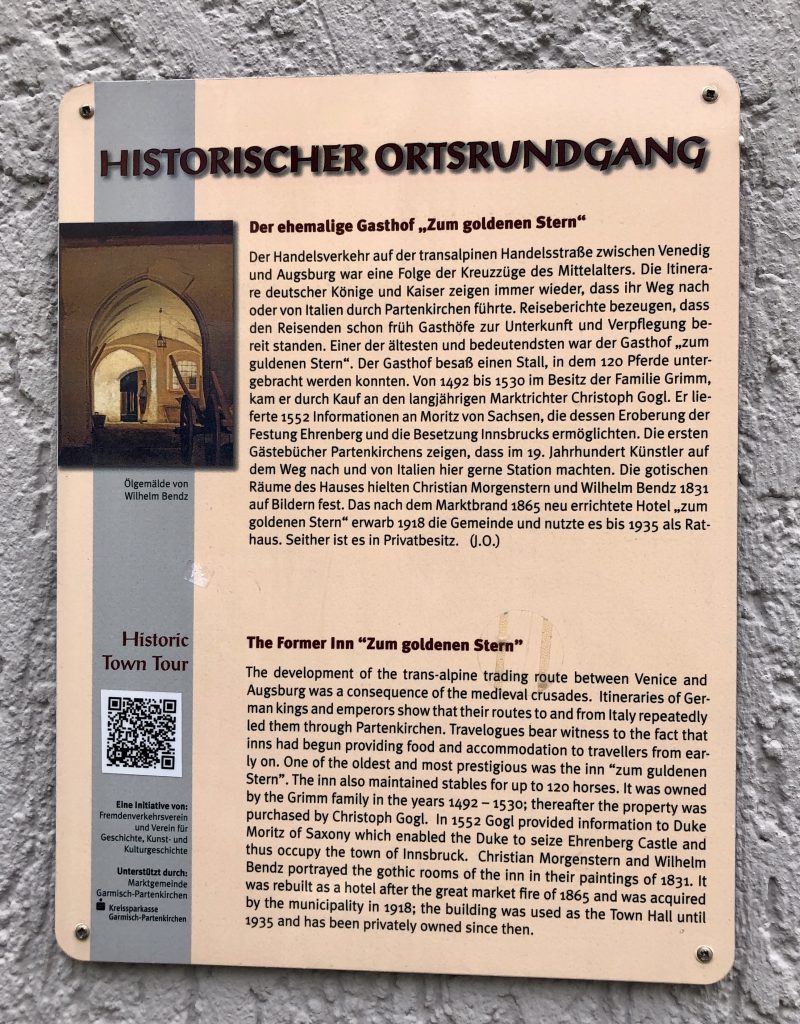

- Historischer Ortsrundgang: Der ehemalige Gasthof „Zum goldenen Stern” / The Former Inn “Zum goldenen Stern” (Plaque on the wall of Ludwigstraße 39). Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, Fremdenverkehrsverein und Verein für Geschichte, Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte.

Lüftlmalerei

A street by street guide to the fresco and facade paintings in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district