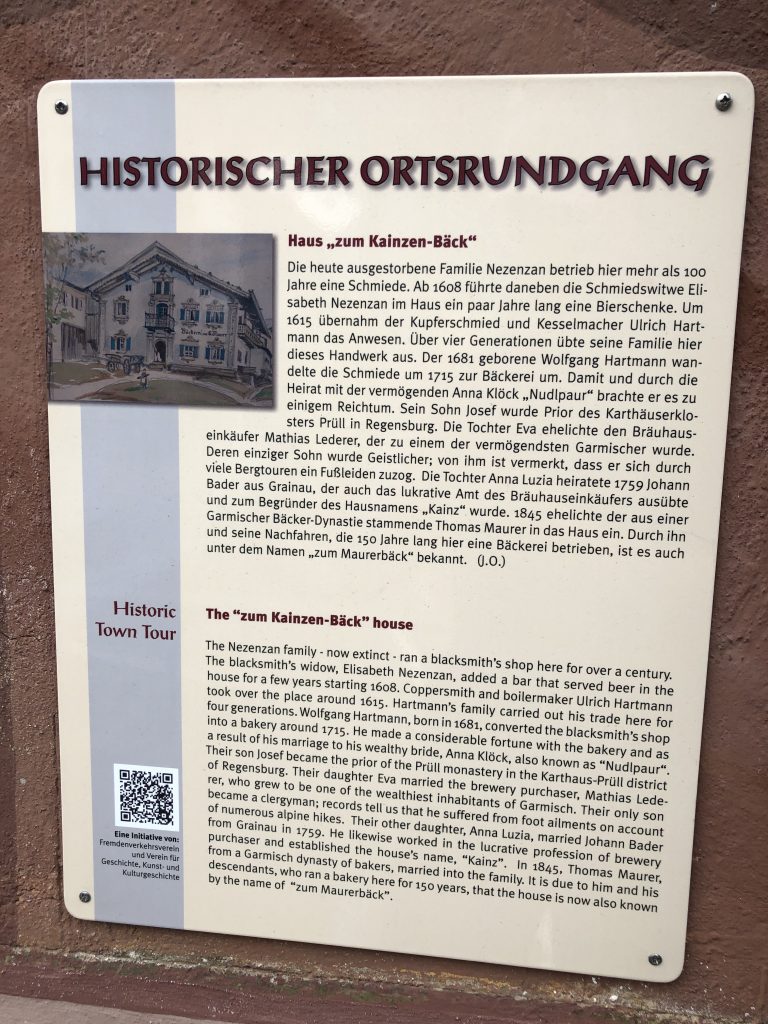

- Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege. Denkmalliste, Markt Garmisch-Partenkirchen. 4 August 2020, www.geodaten.bayern.de/denkmal_static_data/externe_denkmalliste/pdf/denkmalliste_merge_180117.pdf, p. 5: "D-1-80-117-1 Alpspitzstraße 1. Ehem. Bauernhaus, zweigeschossiger Preisdachbau mit Lauben und Balkon, im Kern 1604, südseitiger Zierbund 18. Jh., Eisenbalkon 2. Hälfte 19. Jh., Bemalung modern."

- Historischer Ortstundgang: Haus „zum Kainzen Bäck" / Historic Town Tour: The "zum Kainzen Bäck" House (Plaque on the wall of Alpspitzstraße 1). Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, Fremdenverkehrsverein und Verein für Geschicte, Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte.

- Bierl, Hermann. "Garmisch-Partenkirchen und seine Lüftlmalereien." Mohr, Löwe, Raute. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Landkreises Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Band 18, Verein für Geschichte, Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte im Landkreis Garmisch-Partenkirchen, 2020, p. 13: "018 Alpspitzstraße 1 Isi 57 Rest. Otto-Ertl 2000 erbaut 1604".

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, p. 121: "A 135 Alpspitzstraße 5a, Haus Gerda: Hl. Petrus vor der Peterskirche in Rom; nach 1945."

- Härtl, Rudolf. Heinrich Bickel - Der Freskenmaler von Werdenfels. Adam Verlag, 1990, pp. 58-59: "Vor allem die Mauern, das Arbeitsgerüst und die Leitern werden in augentäuschender Perspektivmalerei wiedergegeben, der „trope-l’oeil”-Eindruck wird noch durch die Tatsache verstärkt, daß sich das Fresko über eine Kante im Winkel von 90º einander gegenüberstehender Mauern erstreckt, wodurch die Malerei noch mehr an augentäuschender „Natürlichkeit” gewinnt.

Während die Bauarbeiter in ihren handwerklichen Verrichtungen realistisch und höchstens in vorsichtiger Idealisierung dargestellt werden, thront über ihnen die Heilige Familie im Stil barocker Sakralmalerei.

Bickel versteht es, diese stistischen Widersprüche durch eine unmittelbare, beinahe selbstverständliche naive „Gegenüberstellung von Himmel und Erde” elegant zu überspielen. Er vereint das scheinbar Unvereinbare, wie es schon die großen Barockmeister in ihren Deckenfresken und Altarblättern getan haben.

Diese Schöpfungen des Malers sind Ausdruck einer echten, naiven Volksfrömmigkeit, die seit jeher das Überirdische wie selbstverständlich in den irdischen Alltag eingreifen ließ, unbekümmert um jegliche Logik und Ratio.

Bickel verstand es, mit diesen Fresken der religiösen Einstellung der altbayerischen Bevölkerung einen kongenialen Ausdruck zu verleihen, einer Frömmigkeit, an der nichts unwahr und verlogen ist. Sie werden damit zu Denkmälern einer ungebrochenen Volkskultur, die einen Bogen von unserer Gegenwart zurück ins Zeitalter des Barock schlägt. Sie übermitteln uns die Empfindung naiv erlebter religiöser Wahrheiten in einer ebenso direkten Darstellungsweise, die allgemein verständlich und nachvollziehbar bleibt, die das Diesses mit dem Jenseits wie selbstverständlich miteinander verbindet.

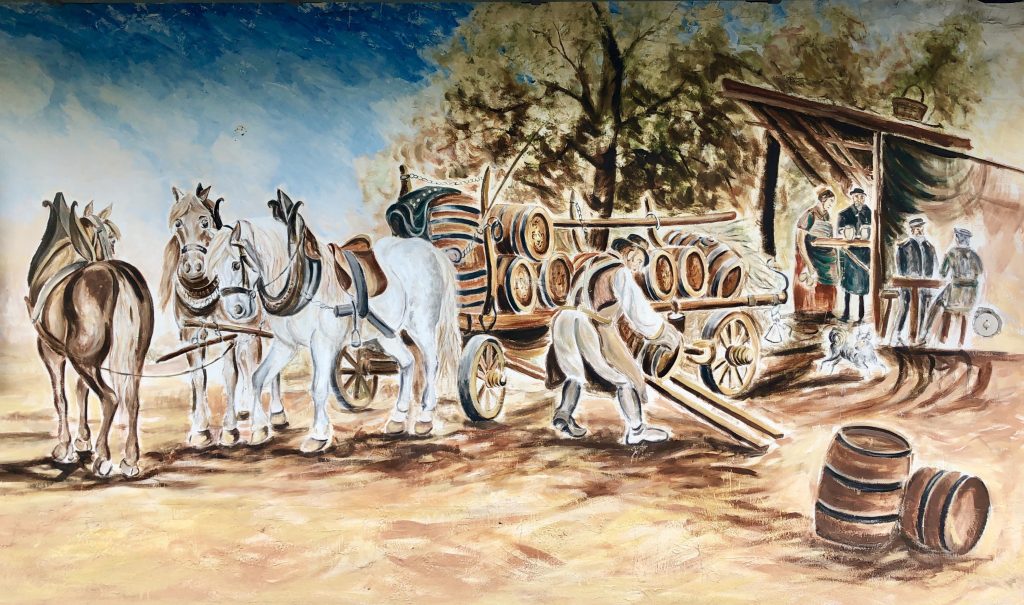

Daneben schildern sie bodenständiges Brauchtum, bewahren es im Bild in unserer technisierten Welt; sie überbrücken den Anachronismus zwischen den Bildern und unserer gänzlich andersgearteten alltäglichen Umwelt, in der Produktionsmethoden bestimmend geworden sind, die mit denen in Bickels Fresken geschilderten nichts mehr gemeinsam haben.

- Besides this particular verse, which has since become a common phrase and inscription, Burmann's works are almost completely unknown today. He was renowned in his own time, however, and otherwise best known for his curious refusal to use the letter "R." In 1788 he published an entire book of poems without once using the letter "R", and is said to have eliminated it from his daily speech, refusing to even say his own last name for some seventeen years.

- Ertl, Michael. “Re: Lueftlmalerei Landhaus Metsch.” Message to the author. 30 September 2020. E-mail.

- Ertl, Michael. “Re: Lueftlmalerei Landhaus Metsch.” Message to the author. 30 September 2020. E-mail.

- "Deutsches Haus in Deutschem Land schirm dich Gott mit starker Hand".

- Rohleder, Franz. Soviel Kreativität ist erlaubt. Merkur.de, 26 June 2009, www.merkur.de/lokales/regionen/soviel-kreativitaet-erlaubt-317515.html. Accessed 29 September 2020: "Urheber des extravaganten Kunstwerks ist Piepers Geselle Marcel Francke. Fast 72 Arbeitsstunden hat der 26-Jährige da rein gesteckt. […] Wie Francke erzählt, habe ein ähnliches Bild in seinen eigenen vier Wänden den Chef inspiriert, auch seine Hauswand mit dem Reißverschluss-Motiv zu dekorieren. "In meinem Schlafzimmer habe ich in diesem Stil schon einen karibischen Sonnenuntergang mit Meer und Palmen gemalt." Davon sei der Meister beeindruckt gewesen und habe auch für seine Hauswand um ein Reißverschluss-Bild gebeten. "Zuerst hatten wir geplant, einen Zypressenweg wie in der Toskana zu malen", sagt Francke. "Aber das hätte wohl nicht ins Ortsbild gepasst." So entschieden sie sich für die Alpspitze."

Lüftlmalerei

A street by street guide to the fresco and facade paintings in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district