Rathausplatz

Rathausplatz 1.

Garmisch-Partenkirchen’s city hall, built in 1935 when the two towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen were bonded together in order to secure a single entry for the Winter Olympics.

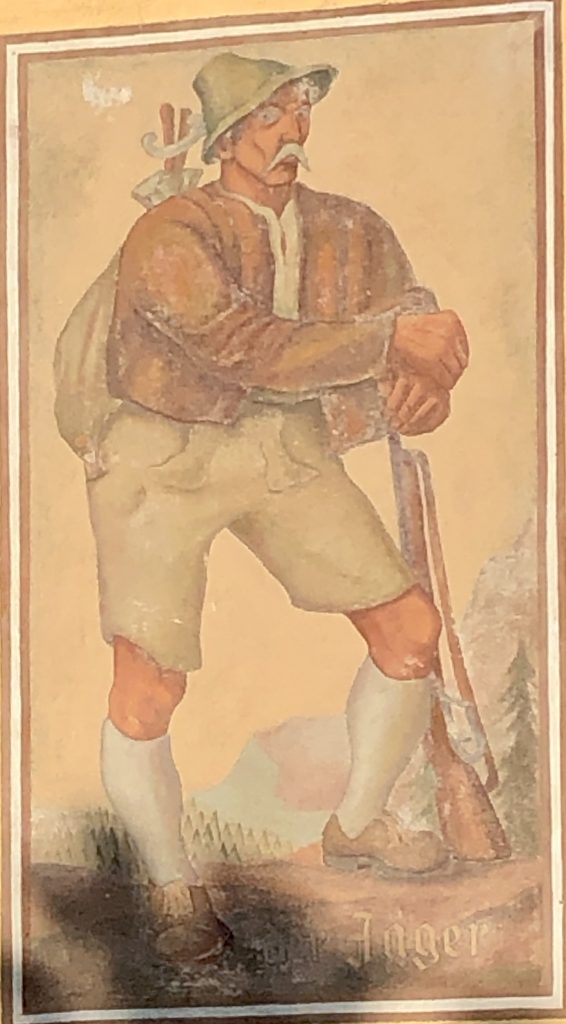

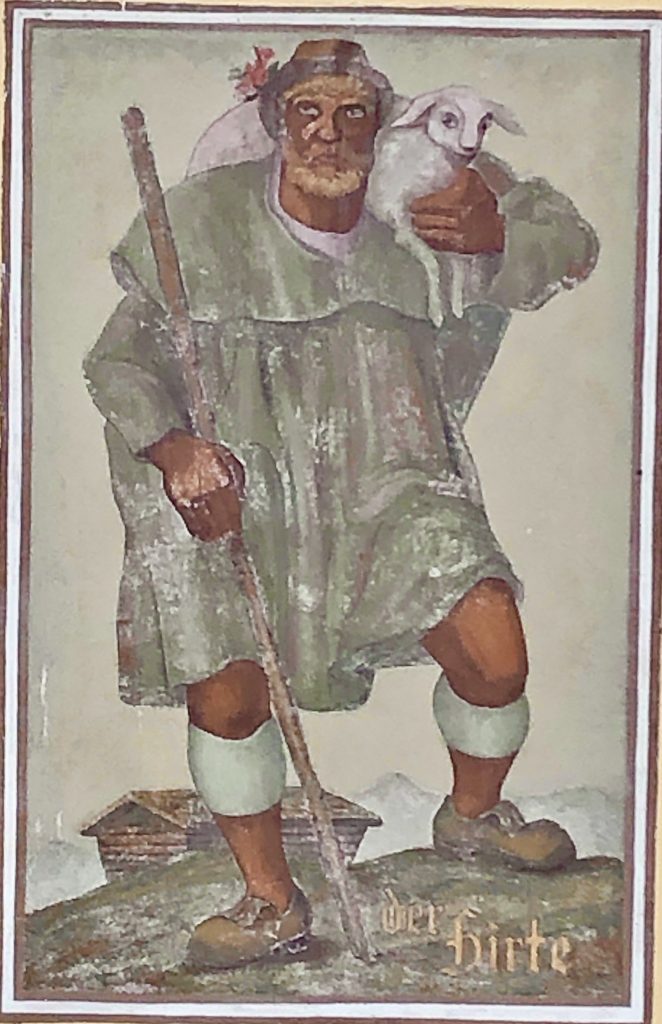

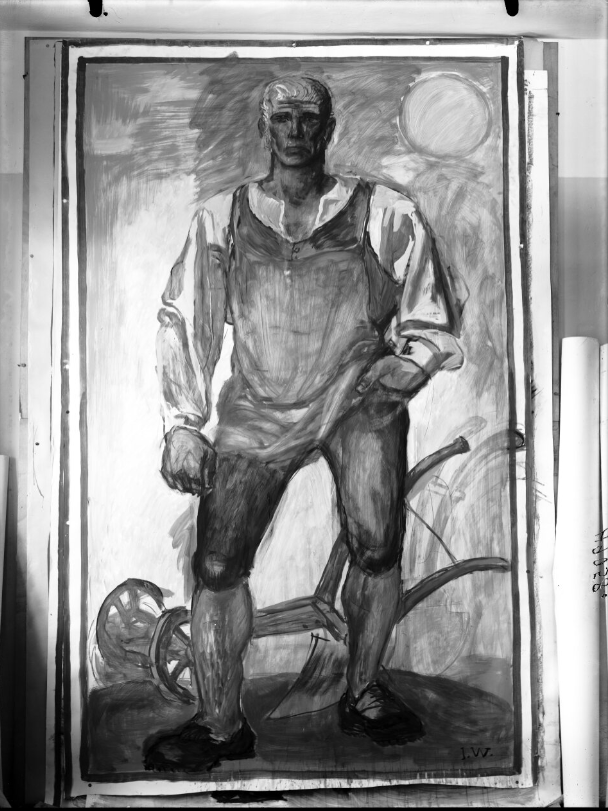

Lüftlmalerei by Oswald E. Bieber and Josef Wackerle, 1935.

“In 1935, the new city hall Garmisch-Partenkirchen was built by the architect Professor Oswald Bieber from Munich. The designs for the frescoes in the town hall were made by Professor Wackerle from Partenkirchen, and they were carried out by painter Karl Gries, Nuremberg. The coat of arms cartridge was designed by Professor Hupp. A number of residential and commercial buildings with facade painting and stucco by Heinrich Bickel later joined. The house fronts were planned based on the style of the old Partenkirchner Ludwigstrasse. The Rathausplatz was intended as a promenade square and for marches and demonstrations, which was previously the purpose of the Gröben Stadium. For this purpose, the Kanker in the area of the Rathausplatz was covered in 1937. The place remained unfinished in its design. It was planned as an ensemble. As on the south and west sides, buildings on the north and east sides should frame it in the same style. For this purpose, a model of the planned overall development was created in 1934. The development of the 1960s in the east is unfortunately not a successful conclusion to the square.”

“The history of Rathausstraße is directly linked to Garmisch-Partenkirchen’s association to form a double location. The term “Garmisch-Partenkirchen” has only officially existed since 1935-01-01. Until then, the development of the two villages Garmisch and Partenkirchen was separate. The double name with hyphen appears in Loiscachboten for the first time from 1882 in connection with requests for a railway connection and is then laid down in 1889 “Main and terminus Garmisch-Partenkirchen”. The timetable also uses this spelling, the Alpine Club Section takes it over in 1893. A committee made up of interested people met in 1919 to work towards a long-standing amalgamation of the two towns. However, the participants in the first public meeting went “satisfied and calm” when it did not happen. In May 1933, the International Olympic Committee commissioned Garmisch-Partenkirchen to host the IV Winter Olympics in 1936. In July of the same year, the Garmisch market council suggested that the two locations should be merged in Partenkirchen: the organization of the Olympiad as a whole could be better carried out. The Partenkirchner were not against it, but they feared incorporation into the now economically stronger Garmisch and thus a threat to their life interests. Only when the location of the new, shared town hall on the Partenkirchner corridor was determined did they agree to the association. But now suddenly the Garmischers didn’t want to: The new town hall could shift the economic focus from Garmisch to the local bar town. The stubborn refusal of the Garmisch municipal councils had consequences: The mayors were quoted in the Bavarian Ministry of the Interior and there they were very clearly asked to either approve the association under the relevant conditions or to draw political consequences: Now those responsible from Garmisch agreed. After all, they had been threatened with being sent to Dachau concentration camp.”

“The new town hall was built in 1935 in suggested forms of the Alpine home style, according to plans by architect Prof. Oswald Bieber, in just 7 months and was expanded as planned in 1940. For the time, a modern building with a meeting and ballroom, letter elevator, telephone system with 60 (!) Extensions of which 44 were connected, with 4 exchange lines and with a payphone for the public. At that time for 551,537 Reichsmarks.”

Rathausplatz 10.

Rathausplatz 11.

The Garmisch-Partenkirchen courthouse.

A lüftlmalerei of Justice with her sword and scales.

However, Justice here isn’t blind.

Rathausplatz 13.

Built by district architect Schweyer, when this building with its arcade arches first opened on Ascension Day, August 15, 1925, it was home to the Werdenfels Museum; it was still in the town of Partenkirchen, which hadn’t yet been combined with nearby Garmisch; there were three separate lüftlmalerei on its walls; and it was only two stories tall.

But not today.

Lost forever, on the east side what is now Rathausplatz 13 was once a mural of Saint Hubertus.

Now, in its place is a Trompe-l’œil of pillars accenting the additional story, reminiscent of the facade the original lüftlmalerei painter Franz Seraph Zwinck put on the front of the Pilatus Haus in Oberammergau.

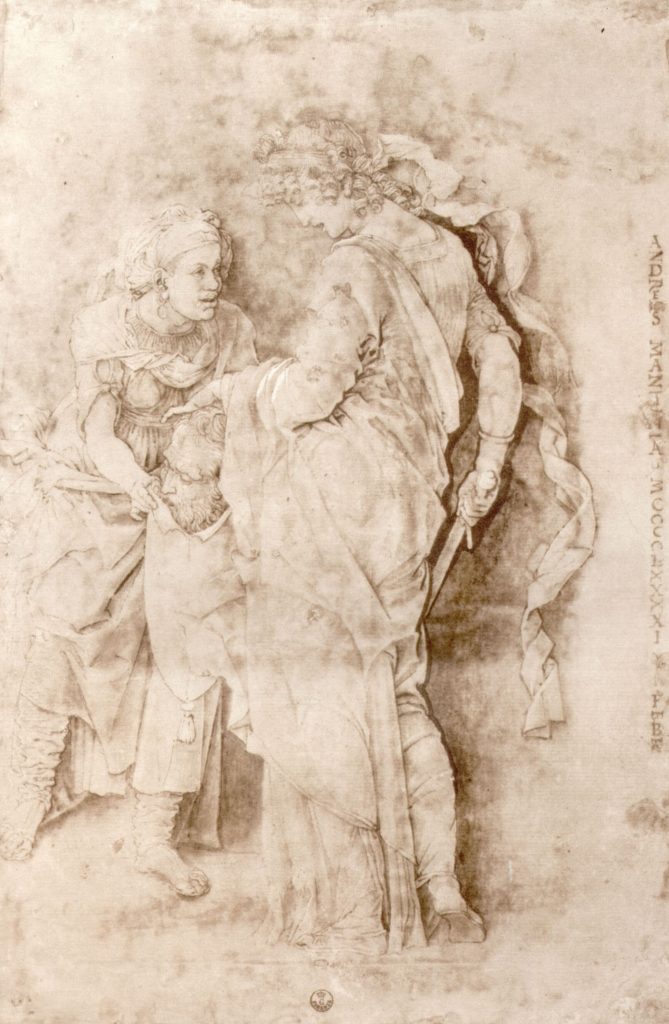

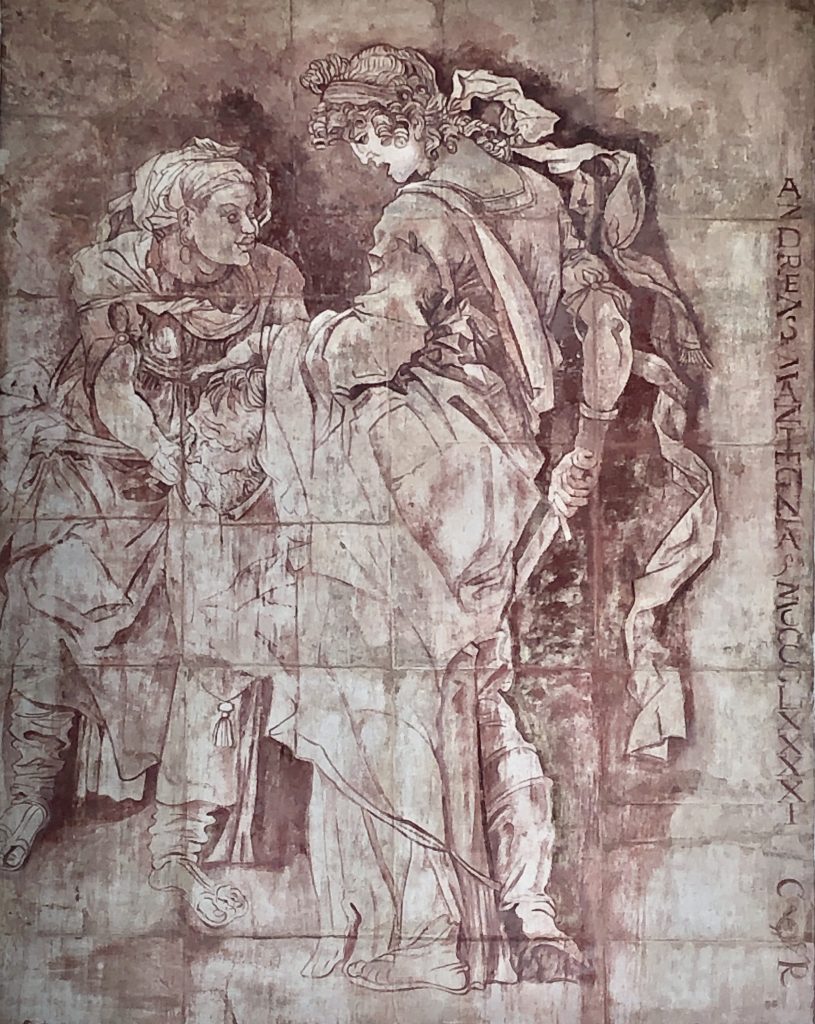

On the west wall, a reproduction of “Judith beheading Holofernes,” a sketch done by Andrea Montegna in 1491.

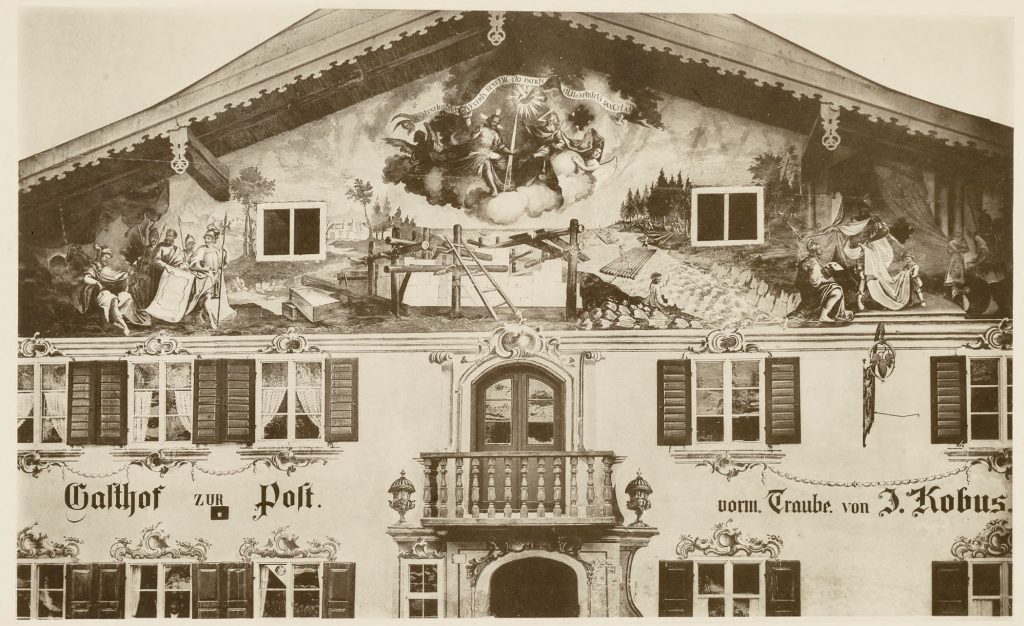

And in the gable on the front, a reproduction of a completely different lüftlmalerei.

In 1778, on the front of the Post Hotel in Garmisch — what is now the ATLAS Posthotel at Marienplatz 12 — Franz Seraph Zwinck painted the Temple of Jerusalem being reconstructed, with the cedars of Lebanon brought by Werdenfelser raftsmen, and Jesus watching over the event from on high.

When that hotel was renovated just before 1900, Zwinck’s mural was lost.

In 1925, Professor Carl Reiser (1877-1950) — who, being the son of a royal Bavarian postman stationed in Partenkirchen, knew the mural on the Garmisch Post Hotel — reproduced Zwinck’s lüftlmalerei almost exactly on the gable of the new Werdenfels District Museum.

Heinrich Bickel renovated Reiser’s mural in the early 1950s.

By 1972, the town decided to sell the the building, as it had become dilapidated and in need of renovation.

In 1973, the museum moved to its current location on Ludwigstraße, and the building at Rathuasplatz 13 was sold to the Hypo-Bank for around 3 million marks. The bank subsequently sold the building to Dr. Stoeppler from Mittenwald, who rented it back to the city for its adult education center, the Volkshochschule.

In 1975, the owner of the building planned to raze it and rebuild something more modern in its place.

While the Denkmalschutz, or the Monument Protection Law, was in effect, protecting those objects deemed to have historical significance, despite the famous frescoes, the building at Rathausplatz didn’t make the list.

In July of 1978, two Garmisch-Partenkirchen citizens, Brigitte Schmidt and Knut Benecke, wrote to the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments, arguing that, even though the building was only just 50 years old, it and its lüftlmalerei ought to be protected.

That November, the State Office agreed.

The building remained exactly as it was, untouched for almost another entire decade, until the summer of 1987. That summer, it was gutted — all but demolished — an addition was built connecting it to its neighbors, and another story was added.

However, the lüftlmalerei on the gable and the image of Judith beheading Holoferno were saved.

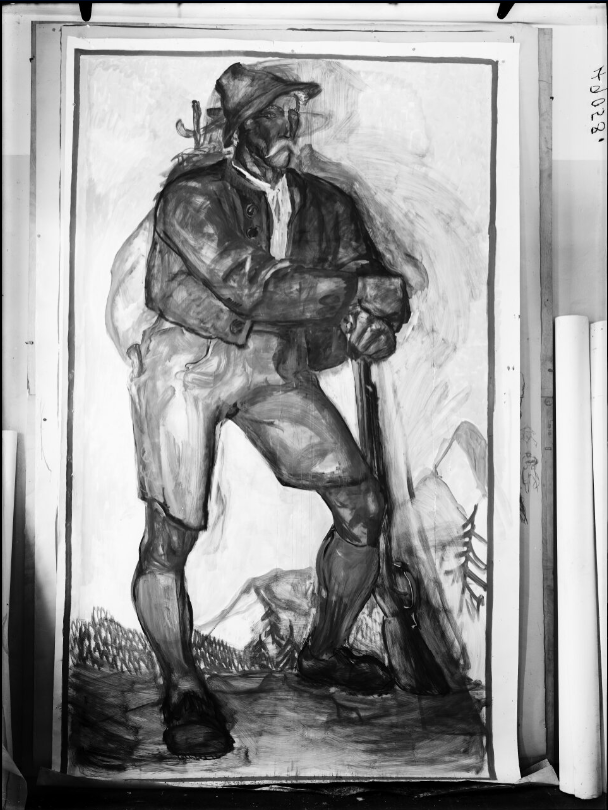

To save them, lüftlmalerei painter and restorer Gerhard Ester first divided the murals into 58 separate squares, glued each square to a special fiberglass linen, and then cut each one from the wall — removed from the masonry and mortar like the pieces of a delicate plaster puzzle. Once removed, each pieces was precisely numbered and catalogued. The pieces were stored over the winter, and then reassembled on the side of the newly renovated building. This aspect of the operation took two months, 100 kilos of special glue, and cost somewhere around 10,000 marks. After drying, the fresco was freed from the layers of fiberglass fabric and cleaning began, which required 160 liters of ethyl acetate. Finally, Ester began the actual restoration, which in this case meant color matching of transitions between damaged and well-preserved areas. Last but not least, he added a baroque frame to the front.

The only of visible remnant of all this dramatic reconstruction today, is the faint grid outline of the nearly 60 separate squares

Rathausplatz 14.

Rathausplatz 15.

Plaster work and lüftlmalerei by Oswald E. Bieber and Heinrich Bickel, 1934.

Online, at the Bavarian State Archives, you can see a photograph of this building taken in 1977, here.

Rathausplatz 17.

Plaster work and lüftlmalerei — personifications of the seasons, “Spring, “Summer,” “Winter,” and “Autumn” — by Karl Gries and Arnulf Albinger, 1935.